Bonds That Didn’t Bind

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” —Maya Angelou

***

“To tell or not tell?” I have been grappling with this question for years. After looking at it from all angles and analyzing the potential consequences of both options, I have finally concluded that it is best to “tell.” The question has to do with whether I disclose an important family secret, revealed to me by my mother ten years ago, or keep it to myself, which will amount to burying it for good, never to surface again. The secret is a tragic one, and deciding what to do with it is not as easy as one might think. On the one hand is the pain and disturbance this knowledge might cause my daughter and perhaps other relatives too (I have been living with that pain for the last ten years), and on the other is the responsibility I owe my late mother who would not have revealed the secret to me if she did not want me to disclose it. It has been a real conundrum, but my mind is made up: “I must tell!”

***

In 2010, many years after I moved to the United States, my mother, who had continued to live in Cyprus and was then an elderly woman, developed a problem in her throat that prevented her from breathing properly. I was in Cyprus that summer to take my mother to Istanbul, where there are more advanced medical facilities, so she could have surgery to address her condition. I stayed with my mother in Istanbul throughout her surgery and recovery, which lasted about a week. This opportunity for just the two of us to spend time together was most welcome, but I didn’t dream it would impel my mother to disclose some shocking facts relating to members of my family—facts that shocked me to the core and gave me a totally new perspective on our family’s past. In particular, during that week, I learned something quite remarkable about my maternal grandmother, Dudu, who had died years earlier, in 1967.

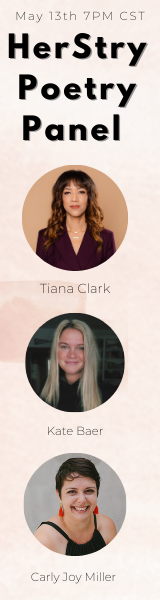

Grandmother Dudu in the early 1960s, at around age sixty-five

For a long time, there was a lot we did not know about Grandmother Dudu. We knew she was a Greek woman, once named Eleni, who was born around 1895 in Potamia, a small village in the Nicosia district of Cyprus where, at the time, Greeks and Turks lived side by side. I vividly remember her beautiful face, especially her large blue eyes. As beautiful as those eyes were, however, I always sensed that they held a dark secret and courted a deep sadness. We knew Grandmother Dudu had lived a very unhappy life. There were whispers in the family that tragedy had stalked her and that she had experienced some very tough times. What these experiences were and when they happened remained a dark secret that she alone kept throughout her entire life.

During the summer of 2010 that all changed. My mother opened up to me, and for the first time talked freely about Grandmother Dudu. When she was done, I was in tears, incredulous at what had happened to my grandmother. When I asked my mother why she had not told me this story before, she said, “It was never the right time.” I now realize the only reason my mother told me the complete story was because she thought she might not see me again when I returned to the United States. Because of her breathing problems she must have thought her death was imminent, so the story was something she wanted to share with me to get it off her chest, just in case.

***

Grandmother Dudu’s mother, also named Dudu, was the daughter of a very poor Turkish family who lived in Potamia. Her short life is estimated to have spanned from 1875 to 1895. Her parents had died when she was young, leaving her with three brothers. Great Grandmother Dudu was a beautiful girl. Mother and daughter looked very much alike. Just like her daughter, she had large, warm blue eyes and always stood out in a crowd for her beauty and grace.

At that time, there was no running water in the homes in Potamia. There were two or three water wells located in the village, but they could not satisfy all the demand of the households. Most water (for drinking, cooking, bathing, etc.) had to be fetched in terracotta urns and clay water jugs from a place called Portolaumo, where the freshwater springs were located—about a mile outside the village. This task usually fell to women and young girls. Even my mother, two generations later, while in her teens, carried water this same way to their home.

According to my mother, for these women and young girls, carrying water from Portolaumo was a difficult and demanding task, but it also offered an opportunity to socialize with their friends and neighbors. They would decide on a schedule from the night before and meet the next day according to that schedule to go to the springs. The groups would meet in their respective neighborhoods and walk to Portolaumo altogether. On the way, they would talk and catch up on the latest news. Sometimes, they would even all sing together. As they passed, almost like a ritual, the village men, especially younger ones, working in the nearby fields and farms, would take a break from their work and line up on the sides of the road to watch them go by.

As a young girl, whenever Great Grandmother Dudu fetched water for their household, she too would be watched by young men lined up on the sides of the road. That is how a young Greek man saw my Great Grandmother Dudu and became attracted to her. This young man decided to marry her against the will of his own family, who objected to the marriage because of Great Grandmother Dudu’s Turkish identity. However, they finally agreed to the match. At that time, and probably even today, the families of good-looking Greek girls asked for relatively high dowries. The payment of dowries is a Greek tradition. It requires the families of young men looking for wives to pay negotiated amounts of money or other assets to their prospective wives’ families prior to the official engagement. The family of this young man realized this particular match could potentially save them money because they could probably get away with paying only a small dowry to Great Grandmother Dudu’s brothers, who were too poor to reject any offer.

This tradition is still in practice today, although it is not as widespread as it used to be. In my view, it is akin to selling one’s daughter (or in this case, sister) to the highest bidder. The family of the young man who was interested in Great Grandmother Dudu offered a modest dowry to her brothers and asked for her hand in marriage. Turkish Cypriot customs did not involve a dowry, so I imagine Great Grandmother Dudu’s brothers felt this circumstance was a stroke of luck. They accepted the offer, and the two married. Their marriage, to this day, remains one of the rare mixed marriages between a Turk and a Greek that ever occurred in Potamia. Shortly after her marriage, Great Grandmother Dudu’s brothers moved to Nicosia and settled there. It is not too far-fetched to imagine that the dowry they received from Great Grandmother Dudu’s in-laws helped finance their resettlement. In Nicosia, one of the brothers became a cook and the other a butcher.

We do not know whether Great Grandmother Dudu was actually interested in the match or if her brothers ever even sought her opinion. Unfortunately, a year after her marriage, Great Grandmother Dudu died while giving birth to her daughter, Eleni. That was sometime around 1895. Eleni was raised by her paternal Greek grandparents. After her mother’s death, Eleni’s father remarried. However, his second wife (a Greek woman) did not want Eleni living in their home because she was part Turkish.

Eleni had a very difficult childhood. Her grandparents, who had reluctantly agreed to her parents’ marriage just a year previously, regarded Eleni as a huge burden and resented her being the daughter of a Turkish woman. Eventually, Eleni grew up and married a Greek man. They had two children together, a boy and a girl. Sadly, Eleni’s husband was abusive and treated her very poorly. Her life was miserable. A young Turkish man then seduced her and convinced her to leave her abusive husband and run away with him, which she did. That young man was my grandfather, Hakkı. It was at that time that Eleni took the name Dudu in honor of her dead mother. Yes, Eleni was indeed my Grandmother Dudu!

Grandmother Dudu’s paternal Greek grandparents, who had raised her and given her away in marriage, were very upset, and so completely rejected her. Her abusive husband (the father of her two children) did not want anything to do with the children and promptly remarried a Greek woman. Her in-laws (the paternal grandparents of her children) were also angry. They definitely did not want their grandchildren to be raised as Turks, so they took custody of the children and did not permit Grandmother Dudu to see them. She was forbidden from having contact or any other kind of interaction with them.

The children were very young, indeed just a few years old. They wanted to see their mother, of course, and cried constantly. It was a sad situation. One night, the children were crying, and the grandparents were upset. They did not know what to do. As punishment, they decided to bury the children, up to their shoulders, in a large box full of garden fertilizer, and they went to bed. The next day they found the children dead, now fully covered by the fertilizer. During the night the two youngsters must have suffocated as they struggled in that box.

It was a tragedy of almost indescribable proportions, and Grandmother Dudu obviously never forgot it. How could she? All her life she blamed herself for the death of her two children. During the summer of 2010, when my mother told me the story of how my grandmother died (a story I had heard many times before), she added a few details I had never heard. She told me that while she was visiting Grandmother Dudu in Lefka, where she lived with my aunt, just before her death, she noticed Grandmother Dudu was praying quite often while she lay in her bed, her eyes closed. My mother was curious because Grandmother Dudu was not a religious woman and my mother had never seen her pray before; she asked for an explanation.

Grandmother Dudu told my mother she had been a good person all her life and had never harmed anyone. So, as she was nearing death, her conscience was clear. However, she had committed one very huge sin she believed God would likely not forgive. This was why she was praying at her final hours. The prayers were about acknowledging one’s sins and asking for God’s forgiveness. Naturally, my mother asked Grandmother Dudu what her sin had been. In deep grief and pain, Grandmother Dudu told my mother the true story of her life, and my mother revealed it to me for the first time in 2010, one day before her throat surgery in Istanbul.

The death of her two firstborn children was the sin for which, on her deathbed, Grandmother Dudu was asking God’s forgiveness. Saddest of all, she could not share her pain with anyone, as the tragedy was kept a secret all those years. The incident was covered up and never reported to the police; no investigation was done, and no one was charged with any wrongdoing. It was treated as if it never happened. My mother only learned of the tragedy at my grandmother’s deathbed, but she never had the opportunity to provide any real comfort to Grandmother Dudu. It was simply too late.

Looking back now, I cannot imagine the extent of the burden Grandmother Dudu must have carried throughout her life. But she wasn’t to blame. She was simply the victim of prejudice and unkindness from others. She suffered alone, with no support from anyone, not even a single word ever from a loved one. Her life must have been a living hell, as shown by the constant pain I remember always being so visible on her face. As a mother myself, I am unable to imagine such continuous pain and the regret she must have felt. Poor, poor, poor Eleni—hers was the greatest of all sorrows! It was not her fault that her father married a Turkish woman. She had nothing to do with that decision. It was not her fault that her first husband turned out to be abusive. Even more likely, she had not freely selected that husband herself; she was likely married off by her paternal grandparents to the suitor asking for the lowest dowry—a generally accepted custom at that time. And yet, she was the one who suffered the consequences of bad decisions made by others.

There is no question that fate had dealt a bad hand to Grandmother Dudu. But clearly, her biggest misfortune was her mixed parentage. If she had not carried the stigma of being the daughter of a Turkish woman, who knows, perhaps she could have lived a better life, and certainly, her two firstborn children might have lived theirs as well. After Grandmother Dudu’s death in 1967, we had very little contact with her family from either the Greek or Turkish side.

***

After learning this story from my mother, it became an important quest to be resolved. I simply could not live with such unknowns about my grandmother. I had to find out more and remove the dark veil covering her past for so long. I began to investigate. I talked with whomever I thought might shed some light. Through my research during the past few years, I was eventually able to track down both the identity and locations of her relatives. Very few of these relatives remember Grandmother Dudu, and even fewer know her tragic real-life story. I now see it as my duty to document Grandmother Dudu’s life, as it is full of teachable moments and valuable lessons. I especially want to honor her legacy after so many years.

At a personal level, I have not yet come to terms fully with my grandmother’s misfortunes and her sad story. I am still trying to process what my mother revealed to me ten years ago. After the revelations, we discussed Grandmother Dudu’s predicament in excruciating detail many times. I am still hoping that one day the sadness I have experienced over this tragedy will come to an end, and the broken heart I have been carrying for the past ten years will mend. I want to heal and find peace! However, one thing I don’t want to do is to forget what happened to Grandmother Dudu. It is important to not forget the past, but rather to learn from it for the future. Otherwise, we are bound to make the same mistakes again and again.

To help achieve this change of heart, I must learn how to better understand and totally forgive the deeply rooted nationalistic and religious sentiments that sometimes become so potent they can drive grandparents to kill their own grandchildren just because of their mother’s birth identity. For me, grappling with these complex realities has been hard. However, I do not intend to give up and will continue to do my best to achieve my stated objective.

-Aysel K. Basci

Aysel K. Basci is a nonfiction writer and literary translator. She was born and raised in Cyprus and moved to the United States in 1975. Aysel is retired and currently resides in the Washington DC area. Her essays and literary translations appeared in the Michigan Quarterly Review, Adelaide Literary Magazine, Entropy, Bosphorus Review of Books, and elsewhere.