A Weekend Away

He had been in Montana for seven days before she got there. He was there with a group of guys—one he had grown up with, the others he had fished with before, on the same river. The house was up on a mesa and they had rented it for ten days. It was her first time in Montana, her first trip away from her children in over a year. She didn’t do any of the planning, but rather showed up feeling as if she was joining in on someone else’s vacation.

The week before, she had been with her kids, alone, for seven days, in August, in Texas. That was the hardest time of the year to be home with children, in her opinion. Realistically, you have twenty minutes outside at 8 AM, before the temperature rises above 95, and twenty minutes in the evening after 6 PM. In between, if you can make it to a pool, that is one good way to spend the day, but even then, the cement is too hot to walk barefoot. Getting back to the car was a panic attack in itself—do you start the car first, and let the air cool down the car seats for a few minutes, even if it meant standing out in the sun for longer than sixty seconds? There was lots of whining, lots of “Mommy, it’s too hot!” To be fair to the kids, she agreed with them. It was too hot—the kind of heat that caused her to see stars on the drive home. Sometimes, when she came inside from the heat, it felt like her face was lifting away from her brain. It had been a long seven days, a long summer, and she was tired. She wanted a vacation, and she was hopeful the trip would be reprieve.

All of the wives flew on the same flight. She didn’t know any of them, while the others had been to Montana together before. When they landed, the others wanted to go to a late lunch and to the liquor store, and then it was an hour and a half drive. She felt like she had to smile and share some things about herself and try to relate to everyone in a way that wasn’t overbearing. Beneath it all, she felt desperate to get to the house, shut the door to a bedroom, and take a shower.

He seemed relaxed and happy when she got there. He was tan, his hair was long, and he hadn’t shaved since she had seen him last. A long gravel road snaked down to the river. The mountains cut a black circle along the horizon all around the house. The sun was setting behind them.

He had obtained the best room in the house, with a king bed and its own bathroom, by saying they were trying to get pregnant.

“I said it in a kind of joking way,” he said.

“Okay,” she said warily, as she realized that this whole group of people she barely knew was going to think they were having sex. The thing was, she didn’t think she should or would be pregnant any time soon. Sometimes they talked about wanting a third child, but mostly in the context of how tired they already were, and how scared they were about her being pregnant again and the complications that might ensue, and how he needed time to focus on his job, and how they couldn’t afford it because they were hardly saving at all. Sometimes their main checking account was overdrawn when she went to get out cash. Usually, she was getting out cash to pay the housekeeper that came once a week, and if their account was overdrawn she would then be left driving around, guilty and stressed, trying to figure out how to pay her. (A check from their small savings?)

She knew she lived in a state of denial regarding their finances. She always felt she should tell the housekeeper not to come anymore, but at the same time, wasn’t sure how she could manage without her, so she never did. Mostly she felt she shouldn’t be staying at home, but rather contributing financially, and yet at the same time there was nothing she wanted more than to stay home with their young children and raise them.

She could tell he had been drinking. Something about his drinking, when he drank daily or often, it got under her skin. Even though she knew it shouldn’t, because he was on vacation, and he should be allowed to drink during the day if he wanted to. But she grew up with parents that drank and fought. Her mother’s drinking turned her bitter and vocal; her father’s quiet until he lost control of the ability to walk, and then to speak clearly. Sometimes there was vicious arguing, sometimes her mother turned on them, especially when they were teenagers. She became more and more belligerent as she got older, so his drinking set off a kind of alarm system inside of her.

But the first night, she had some wine with everyone. She didn’t have any hard rules against it. They went back to their room and had sex. She could tell he was more drunk than she was.

“I finished inside of you,” he said after. She went to the bathroom and started to cry.

Her mind swirled. She thought about money. About a riskier pregnancy. About being present for her current children. What if she got pregnant and couldn’t think clearly, couldn’t write anymore, didn’t feel like herself anymore? Her experience of pregnancy was that the hormones made her feel underwater, made her lose every train of thought, made her do strange things like put her cell phone in the refrigerator or put open jars of tomato sauce back in the pantry, only to be discovered weeks later. She indulged every doubt she had been holding tightly inside, like she was the jar of tomato sauce and the top had been popped open. She summoned up memories of the nausea, the fatigue. She counted the weeks, the days in her head. She was almost certain she was ovulating that weekend. Fuckfuckfuck, she thought. She was terrified to be pregnant again; she knew there was a higher risk of her uterus rupturing after what happened during her second labor. If she did get pregnant, she would have to have another C-section; there was no other option after the complications last time. The thought of being on the operating table again made her want to jump out of her skin. She tried to do the opposite of what they tell you helps with getting pregnant—instead of elevating her hips, she stood for thirty minutes, trying to let it drain out. The wine made her flushed and unsteady.

“I thought we were on the same page,” she whispered angrily when she got back into bed, into the drunken silence. The wind was a paper rustle outside. Her hair was wet on the pillow. She whispered because there was another couple across the hall, who just so happened to be about six months pregnant.

“I thought you would be excited,” he said, and fell asleep quickly.

The next morning, she had a pit of dread in her stomach. It felt like she was already pregnant. The group had planned a hike nearby. It was eight miles through a beautiful forest, up a hillside with rolling views. She enjoyed it, but her mind wandered. They were going to the only nearby town for lunch, where Google confirmed there was a pharmacy. The closest Target or Wal-Mart was two hours away. There were only two rented cars for this large group of ten, so there was no discreet way to drive to Target or Wal-Mart.

The town looked like it was out of an old Western movie, with wooden signs and swinging saloon doors. She saw a pharmacy sign a block down and decided to sneak away as everyone was looking at the lunch menu, telling her husband to order her something. There was a strange nervousness between them. What was she about to do?

I can just see if they sell the pill, she told herself. She looked around at the small town and thought that they probably wouldn’t.

The block to the pharmacy felt especially long. She walked slowly behind a family with two young children. The dad was wearing Chacos and a t-shirt; the mother’s sandy hair was in a braid. She thought about her own beautiful children as she stared at his heels. She wondered what their life might look like if they lived in Montana.

What if somebody asks what I got at the pharmacy, she thought, I should come up with a lie. If they have the pill, I will just buy it and think about it.

In front of the pharmacy, there was a bench and a bear statue, both carved out of a log with a chain saw, heavy with varnish. Inside, there was a soda fountain in front, complete with vinyl bar stools, and a diner partitioned to one side with the menu posted on the wall.

She scanned the aisle that seemed to be assigned to personal care products. There were condoms, tampons, pregnancy tests, miniature bottles of lube, saline solution, Monistat.

“Can I help you find something?” One pharmacist said over the counter. The other pharmacist was speaking with a man who seemed to be angry about something not being ready. Both of their voices were tight and worn out.

“Do you carry the morning-after pill?” she asked, clearing her throat and fighting the urge to whisper. I am a married woman, she told herself. She spun her wedding ring with her thumb. The man turned, glared at her with his eyebrows raised. The made eye contact—a long pause where he looked at her indignantly, accusingly. And then he walked off.

“Oh sure, sweetie,” she said. “Just one minute.” She gingerly handed her a thin paper bag with a box inside, encased in that thick, difficult to open plastic. She needed scissors. She realized if she could have taken it right then, she would have.

She took it to the front. She bought a miniature ibuprofen and a big bottle of water, so the plastic shopping bag looked less suspicious at the lunch table. Back at the restaurant, she put it on the floor beneath the table, between their feet. It felt alive, threatening, clawing to escape, no matter where she set it. He sat across the table and they could barely make eye contact but instead talked about pizza and salad and the nachos that the group had ordered.

She wanted to go back to the house, but the rest of the group wanted to go to a brewery. She felt obligated to go along with what everyone else wanted to do, although she didn’t feel like drinking.

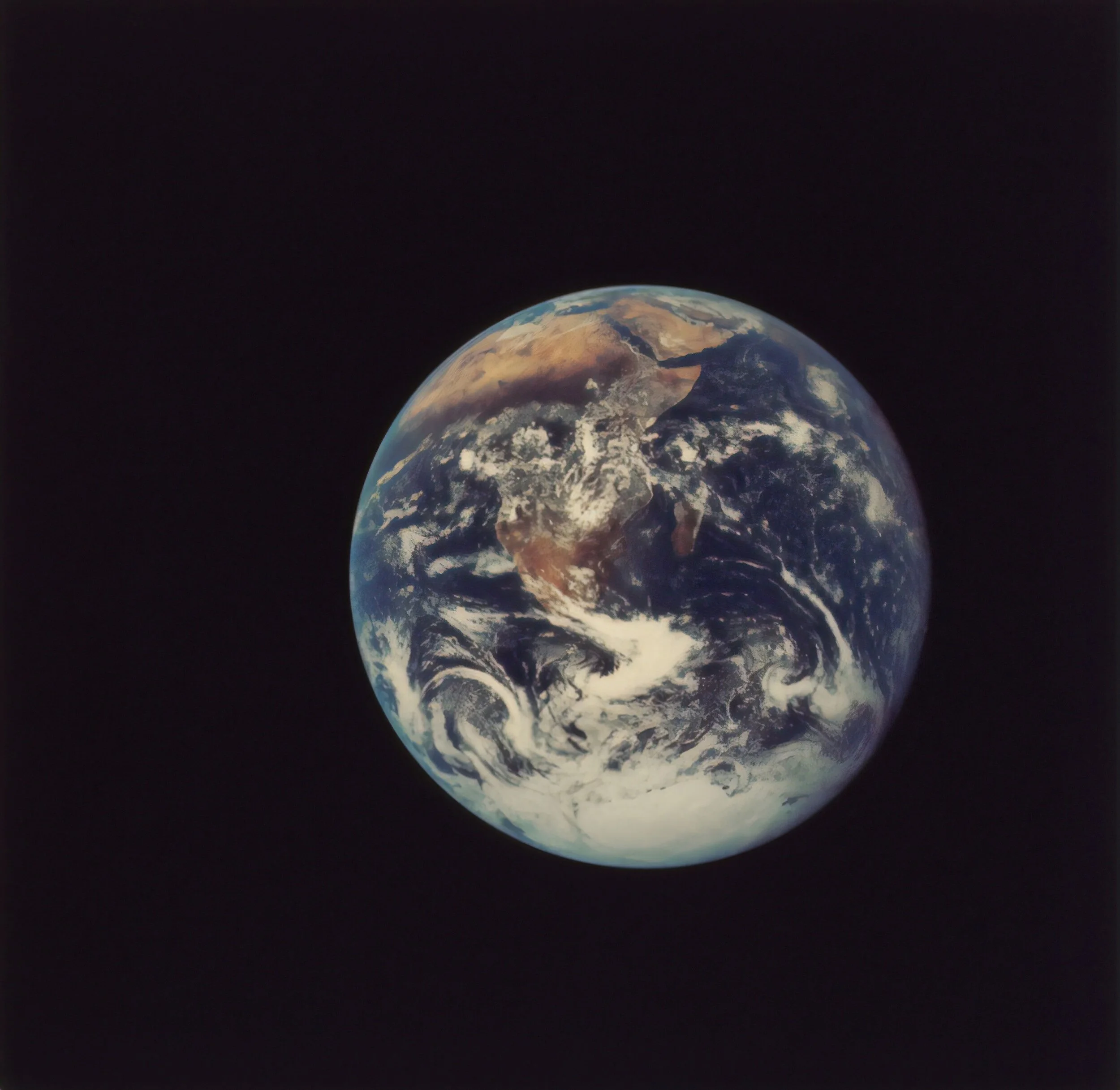

“Are you going to take it?” He asked, as soon as they were alone back in their room. She sat on the edge of the bed looking out at the mountain vista through their window. Those mountains made her feel small. They both agreed, they were financially stressed. At the time, their daughters were nearly two and four, and they already had twenty thousand dollars of tuition due for the upcoming preschool year. They were not sure if they wanted to move, or if they wanted to stay where they were.

“Can you imagine, moving pregnant, or with a new baby?” She asked. “I just started to feel like myself again,” she added, “It is just hard to imagine being pregnant right now.” She was only saying these things so he would understand what she was thinking. She was tired of talking about it.

She thought, This is not relaxing at all.

“It’s not like it’s an abortion,” he said.

“I know,” she said, but she didn’t feel sure. It felt like she was killing something.

There was nothing more to say. She got the little nail scissors from her makeup bag, overflowing with lipstick and concealer and tiny bottles of lotion and face wash and perfume samples. She always overpacked her toiletries. She tried not to think about anything as she cut open the packaging, took the tiny pill, and threw the package in the small trashcan.

That night, at dinner, one of the husbands asked her, “So, when do you think you’ll go for number three?” and for one moment she pictured herself walking out of the restaurant and letting herself cry as she looked at the man’s suggestive smirk. She waited for her husband to answer. He didn’t answer though, and it seemed as if he somehow hadn’t heard the question, as he carefully cut his steak, listening to the other people talking down the table. She had to come up with some normal-seeming, answer: “Who knows!” She forced a smile.

Her sadness felt like a repeated punch to the sternum the rest of the trip, but she told herself again and again she didn’t have a right to be. She was sad when she woke up, sad when she went to bed—anytime she had a break from the small talk and the activities the rest of the group had planned. They didn’t have sex again and she felt slightly guilty about having the special, romantic room with the ensuite bathroom and the mountain views. It felt to her that something was lost between them. Not just the vacation, which they had looked forward to for months, but there was a version of him, even just a drunk version, that was still naive, impractical, and hopeful. And there she was, crushing it with not only real, practical reasons, but fear.

-Anonymous