Chrysalis

Even with a surgical cap and a mask, Mike’s smile still escaped from beyond the barriers of blue polypropylene. He held up the fuzzy hospital socks I was helpless to put on. Without a word, he covered my swollen feet.

“Thanks.”

“You got it.”

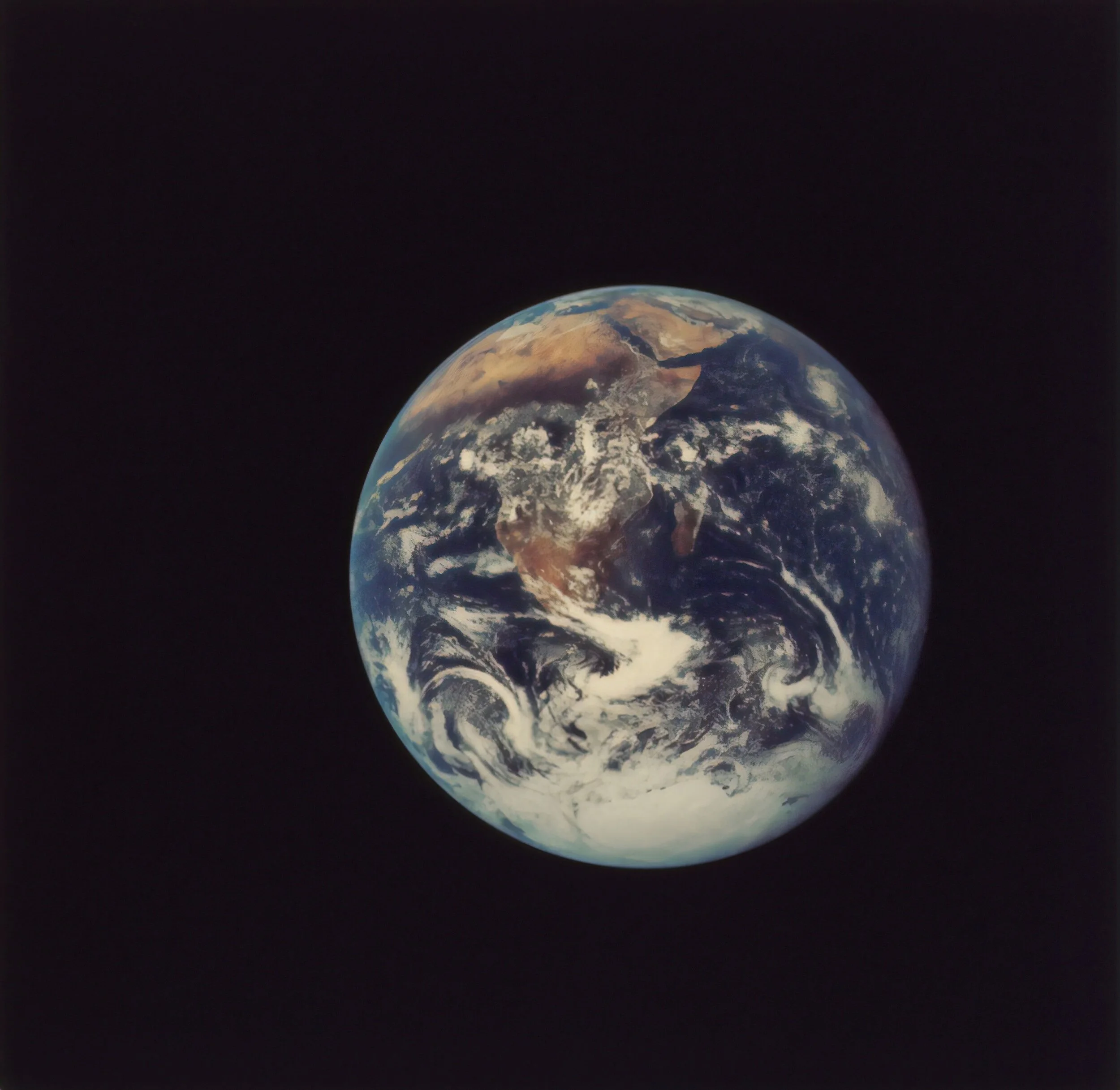

It was just the two of us in the sand-toned room, the two of us and a hundred muted breaths while we waited for the doctor to arrive at the hospital. My water had broken twelve hours ahead of an already scheduled C-section. The babies were stuck in a T-position, my belly rounded but lopsided. I was no longer a full moon, but Saturn with her rings, tilted and cold.

For decades, scientists

have debated the age of Saturn’s rings,

tangled up in different hypotheses about how the planet

got her rings in the first place. At once in resonance, or a gravitational dance, with

the orbit of Neptune best described as a child being pushed on a swing, scientists now

believe that Saturn’s slight tilt—once on par with Jupiter’s—was torqued due to the

yearly incremental outward migration of its largest moon, Titan. But,

until recently, researchers could not definitively state

what might have caused Saturn’s icy rings

and when the event occurred.

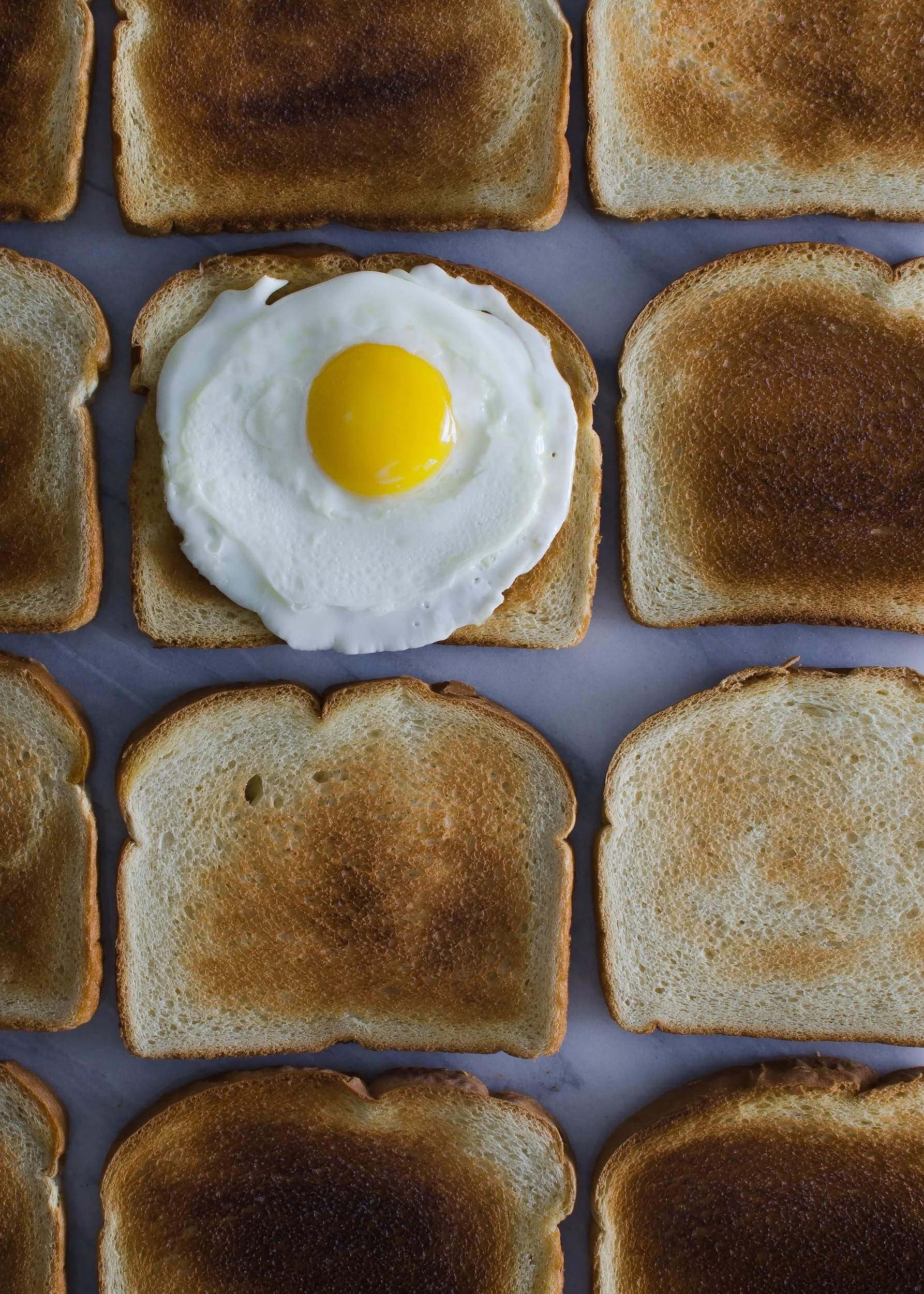

The contractions began to pull me apart, separating a yolk from its shell. A wave of pressure would crack me just a tiny bit more, stealing my breath, my face suspended in time. In walked a nurse, followed by another, and another, and then a new nurse altogether. She was new to the hospital, but not new to the job, a point she wanted to make known. The new nurse had pretty eyes—bright cobalt offset by freshly dyed twilight hair. She was a burst of loud in an otherwise sober room. Nurses dressed in blue scrubs and blue masks glided swiftly but calmly around my body, exchanging pleasantries.

It’s nice to meet you—

Where’d you say you came from—

Such and such…Hospital. But, I’ve been doing this for (some number) amount of years…et cetera.

It was the But that gave her away. She grabbed the Fetal Doppler, which moments before, had been malfunctioning or perhaps not. Either way, they couldn’t find the heartbeats.

“How many weeks is she?” floated a question above me.

“Thirty-seven.”

For twins, a full precession.

“Can you turn on your side?” the nurse asked me.

I gripped the rail of the wobbly bed and rocked onto my right hip. A new splash of waters burst through, drenching the pads beneath me. It took two other nurses to help stabilize me in a side position for the sunset nurse. The room fell quiet, early morning quiet, deathly quiet. The Fetal Doppler slid across the vastness of my greased up belly, across skin pulled taught, a drum without a beat.

Scanning, she finally caught a wave of sound:

Whoosh, whoosh, whoosh…

The other nurses started to exhale.

“No,” she stopped them. “That’s hers.”

New research suggests

Saturn’s rings are as young as 100 million years old,

a far cry from the billions once thought, an even farther cry from the idea

that her rings were once formed at the creation

of our solar system.

I listened to my heart pound through the echo chamber of a silent womb. She moved the wand in a nauseating two-step.

Quick, quick, slow, slow. Quick, quick, slow, slow…

Another wave whoosed into harmony, a faster beat announcing one of the babies.

“That’s Baby B,” she said.

Thumbs up. I gave Mike a smile. He held up his chin with the palm of his hand. He already looked tired. My two and four-year-old daughters had lovingly named their unborn brothers Buster and Bean. We decided Baby B was Bean. Bean was bigger, easier to spot on the ultrasounds, always hiding his twin brother. Buster sat lower in the womb, with a two vessel umbilical chord as opposed to three. He had to work harder at becoming. Only one of Buster’s several ultrasounds revealed his face, every other black and white grainy photo showing two alien hands covering his profile. Buster was in a more difficult position to share a single placenta with a shorter cord and a larger twin brother hovering above him.

The birth

of Saturn’s rings

has everything to do with Titan

and at the same time

nothing at all.

Titan,

merely a moon,

has the most Earth-like atmosphere

in the Solar System, complete with oceans, rain, rivers and lakes,

even ice volcanoes, though none of it water. Nitrogen and methane make up

Titan’s liquid surface—that and hydrocarbon grains.

Titan has sand dunes.

Before

the Cassini spacecraft mission,

and because of the smog-like orange haze

that obstructs her view, scientists once thought the atmospheric chemistry

on Titan would prove “inert and dull.” But according to NASA JPL scientist

Dr. Murthy Gudipati, “…even though Titan receives far less light from the sun and

is much colder. Titan is not a sleeping giant in the lower atmosphere,

but at least half awake

in its chemical

activity."1

I spent the first twelve weeks of their pregnancy in agony. It started as an unsure pregnancy, what I first believed to be a miscarriage, then the discovery of two heartbeats, only to learn they may have been super rare and high-risk twins with a fifty percent mortality rate. Next came a conversation with Mike on what to do if this were the case, to the relief upon learning they were rare but not super rare, and high-risk but not dangerous, to the first time I felt them both move in the womb, to nicknames, to dressing a twin bassinet, to my water breaking, to taking a panic-stricken photo with my daughters at 3:00 AM before heading to the hospital because this was it, to a spinning room searching for signs of life. I knew Buster was alive, simply because I could not bare to imagine that he wasn’t.

Today,

Saturn’s pirouette

and Neptune’s orbit are no longer

in sync. Their frequencies no longer in rhythm.

A child on a swing without

a push.

The new nurse slowed the pace of the Fetal Doppler, a beachcomber looking for an impossible treasure when suddenly she found another whoosh.

“That’s hers, again.”

Because it was slower. Too slow for a baby, until—

“Wait. We got him.” A hypothetical moon.

When NASA’s

Cassini spacecraft took her final dive

into Saturn's atmosphere in 2017, the mission concluded

an astounding thirteen years of data specific to Saturn and her icy moons.

Four years later, researchers have finally pieced together a

leading hypothesis to explain the creation of

Saturn’s rings—the possibility of

a hypothetical moon.

The bed began to roll parting the sea of nurses. The excitement and worry vibrated along the operating corridor. The doctor had finally arrived. My husband kissed my forehead, his hand letting go of mine, before I was hurried into the operating room.

The nurses propelled my body from the bed to the hard cool operating table. The IV cord twisted, tangling me to a life I suddenly feared for. A constellation of thoughts appeared:

One of them might not make it.

And then from an even greater distance, even deeper:

I might be the one who doesn’t make it.

And then from the depth of my being:

What about the girls?

What if this whole pregnancy ended with my death and two motherless girls? It still hadn’t sunk in that it could be two motherless girls and two motherless babies and Mike.

The contractions sped up hard and fast. The babies were trapped. I sat upright, my eyes locking on my doctor’s face. She had pale skin and kind eyes and a voice I could not hear as they rubbed an icy swab in concentric circles along my back, readying my body for a needle to be inserted into my spine when suddenly my left buttock and leg lifted off the table powered by a contraction that wanted to break the whole of me.

It is now believed

that anywhere from 100-200 million years ago,

Saturn’s phantom moon entered an orbital resonance—a gravitational

dance—with Titan. However, Titan was quick, quick. The phantom moon—slow,

slow. The child pushed on the swing too fast, too soon, too close

to Saturn, where her gravitational tides ripped the icy moon

to pieces2. Scientists gave this moon a name:

Chrysalis.

The doctor cried out Hold or maybe it was Wait or Stop. The anesthesiologist, the only man in the room that I can remember, froze. A cold tremor erupted from beneath the fuzzy socks and rippled up my legs and into my hands, pooling in my eyes. The fear of “next”—the wave of weightlessness that would knock me back in a moment’s time, the fear for these lives, the fear for my own, the impossibility of how to bring twins into a family with two other children on educator salaries during a pandemic all washed up on the shore of that metal slab.

“I got you,” my doctor said. She put her hand on my knee. “I got you.”

I nodded and the contraction passed, the needle punctured, and my body floated away from me. The blue nurses guided me downward and anchored me to a board, my arms splayed, a curtain pulled between my breasts and my belly. Mike was escorted in to join me behind the sheet before the first incision was made.

My consciousness slipped into an altered state, not one of this world but not one of a nothing world, either. He smiled as I looked at his upside down face. “You do have a couple grays,” he joked. It was an inside joke lobbed from a mouth beneath a full head of salt and pepper hair.

“Fuck you,” I whispered, as the anesthesiologist tapped and poked my body searching for any feeling.

“Can you feel that?” he asked, poking me with a pin.

“No.”

“Can you feel that?”

“No.”

“Here we go,” the doctor said.

My body rocked and swayed, as the doctor cut and tugged and reached deep into darkness to pull these babies, one with the fading heartbeat, into the world. I waited for a sound, anything to hold onto, when out from this strange land shot a gurgling cry—caught between two worlds—bursting through a wet mouth, welcoming the air. I lifted my head. The doctor held Buster high. My memories catching him forever in a moment, eclipsing the light.

-Lindsey Anthony-Bacchione

1 NASA Team Investigates Complex Chemistry at Titan

2 Saturn may have destroyed one of its moons to make its rings

Lindsey Anthony-Bacchione has been published at The Rumpus, Brevity's Nonfiction Blog, Tupelo Quarterly, Chicago Review of Books, Sentience Lit, About Place Journal and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from Antioch University Los Angeles. She live in Los Angeles with her husband and four young children.