Family Reunion of Urns

My parents raised my brother, Mark, and me in Raleigh, North Carolina, an airplane flight from any relatives. My mother’s sister lived in Oakland, and her brother lived in Los Angeles. We took one family vacation to each during my childhood, because saving money for the future was more important than knowing our cousins. My father’s closest relatives lived in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Detroit, and Toronto. We never visited them. Long-distance phone calls were expensive, and thus infrequent, stilted, and short. But thanks to my paternal grandparents’ example, my current family crosses borders, traumas, and bloodlines, far beyond my family of origin.

Because of our isolation in the South, my childhood concept of family did not include anyone outside my nuclear family. My immigrant parents didn’t utter sayings like “family is everything,” or “you can always count on family,” which would have seemed frivolous and untrue. They didn’t say much at all, unless it was about what needed to be done, who was going where at what time, and what we were having for dinner. Navigating daily life took so much of their attention and energy, little was left for social life and vacation plans.

As a young adult living separately from my parents, I cultivated close relationships with first and second cousins, aunts and uncles who were virtual strangers. Two older cousins lived nearby while I was in graduate school in Boston. I invited myself over for holidays and weekend meals. Their warmth and welcome, which included home-cooked, labor-intensive feasts, cuddling with their toddlers at bedtime, and invitations to stay over, introduced to me a version of family I had not experienced as a child.

This draw towards those with whom I share ancestry had invisible roots in my father’s family. How my paternal grandparents, whom I called Gong Gong and Po Po, reunited at their final resting place is a story of a family sticking together despite great odds. Neither of them fought in any war, and neither ever called Salem, New Hampshire, much less America, “home.” Yet they are buried under the same marker in the veteran’s section of Pine Grove Cemetery in Salem, New Hampshire.

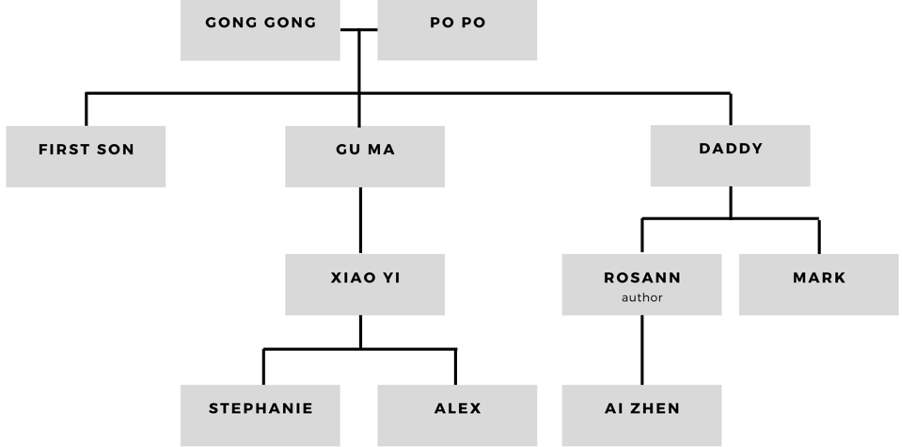

I provide this family tree to help the reader follow the story. Spouses are not shown. Elders are listed by their honorifics, rather than their given names.

My grandfather Gong Gong fled China to Hong Kong in 1957 during the Communist upheaval after the tragic loss of their elder son to mental illness. Gong Gong’s bourgeois background and his ties to the Chinese Civil War’s Nationalist opposition, which supported democracy over dictatorship, meant certain persecution of all male family members who remained in China. He wanted to ensure that his remaining son would have a prosperous future in the free world.

I wonder whether Gong Gong had any inkling as he hugged his wife (my Po Po) and their grown daughter (my Gu Ma) goodbye in Shanghai that he would never see them again.

No one knew the extent of the calamities soon to happen in China. The Chinese Communist Party sought to correct economic gaps by creating a communal society in which distinctions between the peasant and upper classes disappeared. Gong Gong knew that families like theirs, missionary-educated and middle class, at the very least would lose property, status, and power. Yet, I’m sure they had no idea that communication between Chinese people and the outside world would be cut off for decades, that a Great Famine would cause millions to starve to death, and that Mao’s draconian implementation of communism would harm human rights.

From Hong Kong, then a British colony, Gong Gong paid a smuggler to bring my father out of Communist China in the belly of a boat. After working in construction for a couple of years, Daddy gained admission into a doctoral program in engineering in the US.

During those few years when they were on opposite sides of the Pacific, Gong Gong wrote Daddy every two weeks. I imagine he returned to his spare room after a long day at work and a steaming bowl of noodle soup. He wrote his letters on blue Aerogram letter paper, the kind you folded, licked closed, and addressed. Leaving no margins, he used as much of the paper as possible for his words of advice to his son, who was living the life of an international graduate student in California. Gong Gong himself had attended graduate school in Michigan, so he could imagine my father’s life and struggles. Unable to support him in person, Gong Gong felt the key to my father’s success was learning English. So he wrote letters to him in English, even though it was their second language. He encouraged my father to make friends who were not Chinese.

The lines of communication among Gong Gong in Hong Kong, my father in Berkeley, California, and my grandmother Po Po in Shanghai were tenuous. Gong Gong couldn’t write those blue Aerogram letters to his wife, daughter, and baby granddaughter, Xiao Yi, left in Shanghai. Overseas letters landing in a mailbox would alert government officials to the fact that the residents had a close friend or relative outside of China. The blue letters would be opened, read, and censored, so Gong Gong could not ask questions about their lives under Communist rule nor give them information about Daddy in the US; if what mattered couldn’t be written, it was pointless to write at all.

No one knew Gong Gong had chest pain and difficulty breathing. We don’t know how he died, whether it was while sleeping or brushing his teeth or lying down after dinner due to discomfort from eating too much. He was alone when he died, despite having a loving family. When Gong Gong didn’t show up at work for a couple of days, someone knocked on his rooming house door and then entered to find his body. Gong Gong died of heart failure alone in Hong Kong. He sacrificed his life for his family’s future.

Under Mao, Chinese citizens were forbidden to travel and communicate with the outside world. Unable to go to Hong Kong to wrap up Gong Gong’s affairs, Po Po had his ashes shipped to their Shanghai apartment, where the heavy bronze urn kept watch for the next twenty-four years. I imagine it served as a sort of altar, a reminder of Gong Gong’s ultimate sacrifice and the hope it gave the family to have a son thriving in the US.

During these years, owing a debt equal to his father’s life, my father never strayed from the course Gong Gong had envisioned. He fulfilled his duty to become a professor, marry into a “good family,” have children, and earn tenure. Once, learning of his love for architecture, I asked my father why he became an engineering professor. He replied, “Because once you have tenure, you can’t be fired.” As a recent immigrant with too much to prove, he chose financial stability over passion for a more creative career.

Because of Chinese government censorship, my father had no way of sharing his successes, nor his challenges, with his family back in China. Thus, he could not ask his mother and sister for advice about struggles, like racial discrimination against non-White professors at his Southern university, a difficult marriage exacerbated by his wife’s mental illness, a cultural gap between him and his American-born adolescent children, and the isolation of being Chinese in the South.

Mao’s death and China’s burgeoning economic ties to the West in the 1980s allowed my father’s mother and sister to emigrate to Hong Kong to live in a less repressive society. Po Po moved Gong Gong’s urn for a second time to an in-law’s Shanghai apartment for safekeeping. Why move Gong Gong out of his homeland, only to take up valuable space in a tiny Hong Kong apartment?

As soon as China’s government allowed citizens to leave without fear of persecution for the first time in decades, Daddy sponsored my cousin Xiao Yi to live with us and attend the university where he taught.

Xiao Yi graduated, married, had children, and settled in Salem, New Hampshire. In time, Xiao Yi brought her parents and Po Po, who was ninety-nine years old, from Hong Kong to live in Salem. The immigration of this small family was almost complete. But Gong Gong belonged with his family.

My father flew to Shanghai, located the death certificate, transferred his father’s pulverized remains from the bronze urn to a smaller, lighter urn, and checked it as baggage. In Gong Gong’s third post-mortem move, he emerged from the United Airlines baggage carousel at Raleigh Durham Airport.

When Po Po died at 101 years old, I saw my father cry for the first and only time as he mourned his first and strongest bond. He had been separated from his mother for almost forty years. His one attempt to bring her from Hong Kong to live in our home when I was a baby had failed, because his mother’s easy relationship with the baby (me) made his wife (my mother) insecure.

My aunt and uncle searched for a final resting place for Gong Gong and Po Po. They chose Pine Grove Cemetery where they bought four plots. When my parents learned that the plots were only one hundred dollars each, they bought two plots as well. It didn’t seem to matter that the plots were eight hundred miles from the place my parents called home.

“Daddy, why did you buy burial plots in Salem, New Hampshire, when you have lived in Raleigh, North Carolina, for over thirty years?” I asked over the phone from my Boston home. To me, Salem was a place to conduct errands at strip malls and big box stores with parking lots and no sales tax, or to buy a home and commute to Boston like my cousin. I imagined a final resting place that was grander, more fitting with their histories of migration due to war, revolution, and sacrifice.

In his matter-of-fact way, Daddy answered, “Because they were cheap, and my sister said it’s pretty. That way, we can all be together, and you and Xiao Yi can visit us.” I’ve often wondered whether immigration makes people not only irrationally frugal, but also driven by the practical rather than emotional. My parents don’t have the luxury of sentimentality.

My family now owns six plots in the veteran’s section of a cemetery in a place far from China both in distance and culture, a small town with three percent Asian residents, not dissimilar to how I grew up in Raleigh. At the end of his urn’s fourth and final journey, Gong Gong and Po Po were reunited at Pine Grove Cemetery.

Gong Gong never found out how his sacrifice of leaving his family in Shanghai ended. My father fulfilled his father’s dreams and enabled the rest of the family to immigrate to and prosper in the US.

Even though my parents did not have the means, the freedom, nor the energy to foster strong family bonds across distance, I prioritize quality time with family and friends. If it can’t happen at home, I make family dinner happen in cars with leftovers, or in parking lots with takeout. Even though it’s not the most efficient way to do errands, on Saturdays I insist that all three of us pile into the car. Family traditions, rituals, and vacations form my daughter’s childhood memories. I want her to know and love all of her aunts, uncles, and cousins, including those who are not related to us, so we dine and vacation together, call and text.

Gong Gong’s and Po Po’s great-grandchildren did not have to endure the trials of war, immigration, and economic hardship that their ancestors did. And they have never visited Pine Grove Cemetery. But they have been raised to know families stick together, even in death, despite the separation caused by political upheaval and migration across oceans and continents. I strive to uphold my grandparents’ legacy, the lesson that home is anywhere and everywhere one is cherished and nurtured.

-Rosann Tung

Rosann Tung began writing creative nonfiction after a career conducting research and advocacy for racial justice in public education. Her work has been published in the Boston Globe and is forthcoming in the Main Street Rag anthology, “A Tether to This World: Mental Health Recovery Stories.” Instagram: rosann.tung. Twitter: @RosannTung. This piece was previously published in Sampan, a biweekly Boston Chinese-English newspaper. Read it here: https://sampan.org/from-china-to-america-a-family-finds-its-final-resting-place/