A Gamble

“Well, Ms. Song, I have to say, you’re pretty darn unlucky.” I thought about reminding her again—for maybe the fiftieth time—to call me Julie, but after two years of her ignoring my request, the point was moot. Besides, I couldn’t remind her, I was weeping again. Mike took two steps across the tiny doctor’s office and grabbed a tissue from the box, wiping the salty black tracks that muddied my cheeks. Dr. F pursed her lips, tightly holding back any words of wisdom or comfort she might have had. Her face said it all: pity and boredom. This was just another day as an infertility specialist.

When I was twenty-seven, I stumbled across a magazine article titled “Ten Things You Should Know or Do Before You turn thirty.” I had most of my bases covered: figure out your career path (check), open a retirement account (check), travel alone (check). I waffled on the last item on the list: decide if you want to have children.

My mom suffered from what Betty Friedan coined “The problem with no name.” She lacked fulfillment outside of her role as a traditional housewife and mother. Her chronic unhappiness stemmed from the mundane chores of mothering children she never wanted in an unhappy marriage. She made no secret of her feelings.

When I was a teenager, I delighted in staying up late with her after my siblings retired to their rooms. We convened at the round glass kitchen table, clean from our showers, and ready for bed. I wore a fraying t shirt and faded pink pajama bottoms. She wore a silk and lace magenta floor length nightgown highlighting her jutting clavicles. She brought a tray of soju and anju (Korean snacks to accompany drinking). After a few swigs of soju and a deep inhale of her Capri cigarette, she declared in Korean, “Children ruin your life. What’s the point of having children? The single life is best.” I wasn’t sure what my siblings and I had done to offend her, but was acutely aware that our existence burdened her, and she found little to no joy in motherhood.

As more soju coursed through her, her diatribe continued, “I was so stupid. My in laws told me to have another kid, and another kid. What’s the point? Maybe just one was enough. But your dad wanted a son, so we kept having another one and another one. Actually, its better to have no kids. Then you have freedom.” Rather than finding offense in her sentiment, I wrested her resentment as my own, and sought to live the life she would have wanted.

Armed with her wisdom, I resolved kids were not for me. Not having children appealed to my rational side: kids were time consuming and expensive, and there seemed to be little (if any!) return on the investment. The mere thought of tending to a screaming infant terrified me. When a friend of mine asked me if I wanted to hold her newborn, I backed away slowly and said, “Uh… I don’t think so. But thank you.”

Women like Gloria Steinem, Oprah, and Helen Mirren who prioritized career over family became my idols. And so, I breezed through college, stumbled through graduate school, and finished my PhD, landing a tenure track professorship by age thirty. In academia, I was in the infancy of my profession, with endless possibilities on the horizon. The possibility of actual infants, however, was fading into the twilight. Little did I know that this life altering decision I made in my twenties would haunt me later in life.

Enter Mike. We were in our early thirties and living in Los Angeles, just blocks away from one another. I was licking my wounds from finally leaving a tumultuous five-year relationship and not seeking anything serious. He picked me up and opened my door for our first date, a rarity in modern urban times. We shared a bottle of Garnacha and tapas at my favorite restaurant, the dim red lighting accentuating his bulky biceps and dimple-flanked grin. I found his intellectual curiosity and progressive stance on social issues refreshing. Much as I tried, I couldn’t resist our instant chemistry and witty banter. Hot and steamy evolved to comfortable companionship, and we lazed away Friday nights drinking wine, talking politics, and playing Taboo, Parcheesi and Boggle. We spent slow Saturday mornings at Bagel Nosh curled against one another in cheap red vinyl seats, sipping coffee and reading LA Weekly.

A few months into our relationship, I cautiously ventured, spreading cream cheese on my sesame bagel, “How would you feel if we never had kids?”

Without a beat, he replied, “I would be really disappointed.” He didn’t return the question, perhaps assuming, like most people, that all women inherently covet children. I didn’t tell him that having children was low on my priority list—so low, in fact, that it didn’t make the list. I wanted to drink wine in the South of France, peruse art in museums across the globe, read thick novels, and attend concerts. Diapers and bottles didn’t fit into that equation. I wanted to be with Mike, but having children was out of the question for me. Would I be enough for him to forego his desire to have kids? I didn’t tell him where I stood on the issue, fearing that I wouldn’t be enough for him.

Eventually, Mike introduced me to his parents, who flew in from Philadelphia. He picked me up and drove us to the Intercontinental Hotel. The valet took the car, and we strolled hand in hand through the sliding glass doors. Jeff and Nancy were sipping cocktails at a long wooden table in the hotel’s restaurant. As we approached, they stood up and hugged Mike. I hung back, reveling in their joyful reunion.

“This is Julie, the one I’ve been telling you about,” Mike said, presenting me like a trophy. I tried to extend my hand, but Nancy folded me into a hug, followed by Jeff doing the same. We ordered a bottle of wine for the table and perused the menu. As we imbibed and dined, the conversation never lulled. Jeff asked me about my childhood, parents, and my occupation. Nancy beamed, and Mike monitored with approving eyes.

Prior to this meeting, I had met two of my boyfriend’s parents. Like me, my boyfriends were children of Asian immigrants who struggled to occupy two worlds: that from which their parents came, and American, where assimilation is necessary for survival. My high school sweetheart was Filipino. His parents spoke limited English, and our conversations never extended beyond platitudes. My second boyfriend was Korean, like me. Despite sharing the same ethnic background, his parents were staunchly Catholic, and suspicious of my atheism. “Marriage will ruin your life,” his mother would dramatically sigh whenever we’d visit. She directed her son not to marry, perhaps fearing the wrath of God’s judgment of him not marrying a nice Catholic girl. This bit of advice left a bitter taste on my tongue, obliterating any desire to improve my Korean to better communicate with them.

I was astonished to watch Mike and his parents talk about current events, philosophical ideas, books, art, and music. There was no language barrier that divided the two generations, leaving each lacking words to convey the depth of their thoughts. While it wasn’t fair to compare my family to Mike’s, I couldn’t help but notice the stark contrast. Unlike my family, who was lock-stepped in cultural edicts of authoritarian parenting with a constant stream of judgment and criticism, he and his parents were egalitarian. Acceptance and respect were evident in their relationship. My father equated fatherhood with providing for his family. His workday began before sunrise and ended near midnight, seven days a week. He never asked us anything beyond, “You okay?” The answer always being, “Yes.” Watching Jeff and Mike banter, exchange jokes, and share their feelings was jarring. My grasp of family and motherhood, a fistful of sand comprised of my parents’ angst, complaints, and frustration was slipping through my fingers. I opened my hand and let it all blow away, allowing the possibility for a new narrative.

I started to pay attention to Mike’s potential parenting skills. Lola, his Pug was afflicted with Inflammatory Bowel Disorder. Mike took her to vet appointment after vet appointment and experimented with various types of foods to alleviate Lola’s bouts of explosive diarrhea. I watched as he prepared her food every week, portioning three ounces of ground turkey, chopped carrots, chopped broccoli, and sweet potatoes into plastic Tupperware containers. When she whined in the dead of night, he bolted out of bed and ran down three flights of stairs, carrying her under his arm like a football. There was no doubt that Mike would be a stellar father. Maybe I just needed to be an okay mother. Mathematically, stellar parenting plus okay parenting equals decent parenting, right? Maybe I could have a happy family life with him. Maybe not all families were as dysfunctional as mine. Maybe motherhood did not have to equate to misery. I was intrigued by the possibility of seeking happiness in the careful balance of career and family.

Eventually, we married. I went off of birth control, assuming I would easily get pregnant after too many margaritas at Taco Tuesday. Apparently, tequila isn’t such a magical elixir after all. An ovulation calendar ousted romance and spontaneity from our bedroom. Sex became a chore for us both, a debilitating blow to my ego and to our relationship. Month after month, failed pregnancy tests led to frustration and tears. Irony is spending your adult life doing everything possible not to get pregnant only to realize you needn’t have worried.

Eighteen months later, I found myself staring at a sign on the wall: “Infertility Department.” Couldn’t they offer a shred of optimism by re-branding it the “Fertility Department?” After probing my insides with a doppler and reviewing my medical history, Dr. F outlined the problems with my plumbing. Then she reached down, opened a drawer in her desk, pulled out a sheet of paper, and slid it across to Mike and me.

“We can start with intrauterine insemination; that’s just about $600. But given your circumstances, I would suggest skipping that and going to in vitro fertilization. That’s about $7,000 for the meds and $9,000 for the procedure. But if you go that route, I’d like to put you on human growth hormones, which is an additional $2,000.”

“Why would I need to go on human growth hormones?” I asked, trying to tally up the exorbitant amounts being thrown at me.

“HGH helps the fetus develop, and can increase the possibility of a successful pregnancy. But, given your low egg reserves and fibroids, I don’t know if that is how you should spend your money. I recommend using a donor egg.” When she saw me tearing up, her eyes softened behind her purple rimmed eyeglasses, and she ended the sentence with a soft “okay?” I nodded numbly.

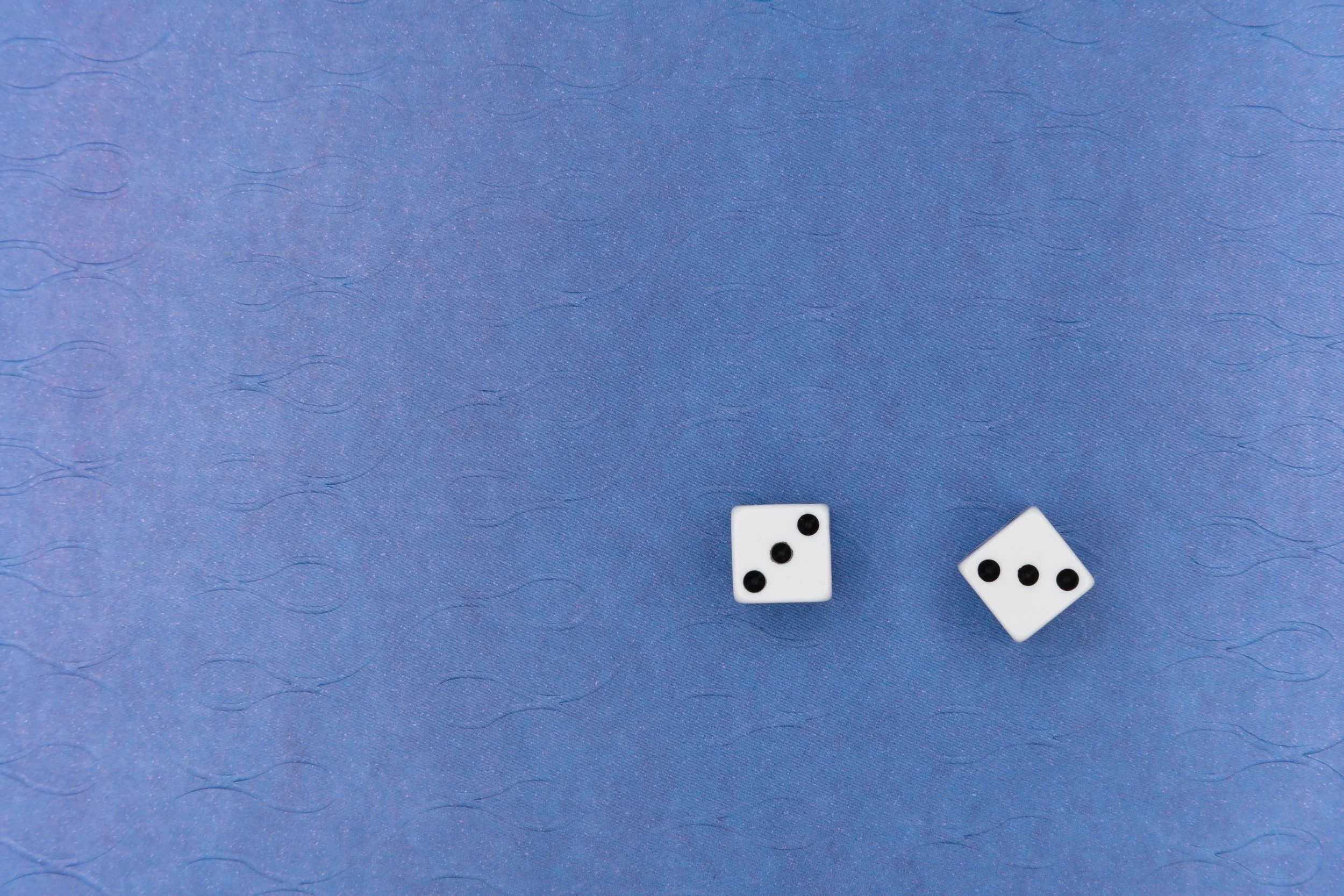

“It is kind of like gambling,” she continued, “and you just have to choose the right bet.”

A year passed before Mike and I decided to move forward. We had gone to several other fertility specialists, all who advised us not to waste our money. It seemed that Dr. F. was the only one who had a scrap of optimism, and so we returned to her casino. We shuffled into Dr. F’s examination room once again. I disrobed, donned the hospital gown, and perched on the edge of the gynecological chair, waiting for her. Mike paced the office, surveying the medical equipment. She strode into the room. The sliver of human warmth had evaporated, and Dr. F was all business.

“Ms. Song, Mr. Scharf. It has been a while,” she said, clasping our file in her hand.

“Hi Dr. F. Thank you for seeing us again. We finally decided to move forward with invitro. I’m sorry it took us so long,” I said apologizing. “We needed some time to think, and, well, we went to Europe, and then life kind of got in the way.” She raised her eyebrow when I mentioned that we traveled to Europe.

“I wish you two made this decision sooner. Your egg reserves are really low, and time is working against you.” I shrunk in my seat, like a student being reprimanded by the principal.

Fortunately, Mike spoke up. “We understand that. We needed a break, and the timing was off for us. But we are here now, and ready.” She pursed her lips.

“Are you sure this is the path you want to take? The chance of the you producing a quality egg is extremely low. Your endometrium quality is questionable, and you have unusually large fibroids. I don’t think you have a very good chance of a successful pregnancy. I urge you to consider a donor egg, and a surrogate to carry to term.”

This time I didn’t cry. Fuck her and her litany of bad news. Fuck the fibroids, these deadbeat squatters in my uterus. Fuck the ovarian cysts, and the endometriosis I’d battled for 15 years. A storm of indignation roiled inside me. I held my head up, looked her in the eye, and calmly said “I.... I still want to try. I need to give my eggs and uterus a shot.” Mike squeezed my shoulder through the hospital gown.

She snapped the folder shut and said “Okay. I’ll let you get changed and then we’ll chat in my office.” I knew that my bet wasn’t prudent. This was a $20,000 single-number bet at the roulette table.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Mike asked, handing me my pants. I pulled them on, along with the shirt I had carefully set out the night before. I planned my outfits like I organized my life—calculating all possible factors and making informed decisions. No matter how strategic, however, I could have never planned for this. I thought I had life figured out, and Fate laughed at me. I wanted to look Fate straight in her face and beat the odds. But who was I kidding? This was bigger than me. I avoided Mike’s gaze, letting silence lapse a few seconds longer.

Finally, I uttered the two most honest words I could think of at the moment: “Not really.” How could I be sure about pursuing a path I thought I never wanted? I spent most of my life with my mother’s cautions echoing in my head and dodging the cultural expectations of compulsory motherhood. And here I was, at age 37, grasping at straws in an attempt forge a new path, but it felt futile. I interrogated every stage of my life, wondering what I could have done differently. Should have I married my high school sweetheart? Should I not have had so many flings in grad school? Was I supposed to settle down in my 20s instead of focusing on my education and career? Did I really need to spend so much of my thirties focusing on work and traveling? Was this moment karmic punishment for a series of wrong decisions? What was wrong with me where I lacked the seemingly biological impulse to procreate other women so guilelessly embraced? I had no answers, only uncertainty. An abyss of the unknown gaped ahead of me, and I put my money on hope.

-Julie Song

Julie Song is a Brooklyn-born daughter of two Korean immigrants who chased a dream in America. She grew up in Southern California, where she completed her doctorate in Sociology. She currently lives in the Los Angeles metropolitan area with her spouse, son, and two aging dogs.