Not Your Mother's Meatloaf

I.

Tucked between the food-stained pages of my old Betty Crocker cookbook is a handwritten recipe for meatloaf. It’s written on the back of a menu from Gustaf Anders, the Swedish restaurant in Southern California where my stepbrother, John, once waited tables. It was 1992, I think, and John and his Norwegian wife were in the middle of a divorce. Or maybe it had already happened. We were drinking a lot and smoking weed in those days. We had flown back from Norway together, drunk for the entire fourteen hour flight from Oslo to Los Angeles, with a stopover in New York for Customs. I think it was New York; I was in a brownout then. The valium and booze had performed their customary magic. What I remember: putrid green cinderblock walls and men in uniforms. Our bags were screened and some item was questioned and we almost missed the connecting flight. We reeked of Marlboros and sweat and Kahlua. We’d drunk the liquor cart dry.

II.

We moved into an apartment in Huntington Beach shortly after that. John had brought along a briefcase (empty) and lace doily (his portion of the divorce settlement). I had a few pieces of shitty furniture I’d thrown in an equally shitty storage unit when I’d left to spend a year in Norway with the man I’d hoped to marry and didn’t, along with the bright green footlocker of clothes I’d dragged along from Maine to Los Angeles seven years before. We bought a gaudy floral loveseat and couch ensemble from the Rent-to-Buy furniture store. Our new apartment, the ground floor of a quadruplex, never got much sun. We played gin rummy and drank wine and listened to a-ha CDs. The carpet smelled of bong water. It might have been variegated brown and white shag. Everything was hazy then.

III.

I do not recall my mother ever making meatloaf when I was a kid. She made peanut loaf once, during her vegetarian phase and called it “better than meatloaf loaf” and, let me tell you, it was…not. There were shredded carrots in it and even my father, who ate burnt toast and stale crackers and scraped the mold off the cheese sometimes because he grew up in the Depression and that’s what you did, even my father agreed that it was not one of her better dishes.

I do not recall ever making meatloaf in my early years as a starter wife: a 19-year-old aproned Suzy Homemaker baking coffee cake in a tiny mobile home kitchen. I barely recall making this recipe when John first shared it, because in that era of my life—late twenties, early thirties—I was drunk more than I was sober. At least it felt that way. But I must have made the meatloaf a few times, for it eventually wound up on the pages of Cook & Tell, my mother’s monthly cooking newsletter. She’d renamed it “Amie’s Good Meatloaf,” and when it was later published in her cookbook, she elevated its status to “great” in the recipe headnotes.

IV.

Years later, after I quit my job and returned to Maine and the island farmhouse of my childhood where my mother had baked and cooked and written all her newsletters until she could no longer follow a recipe, I’d served the meatloaf, along with the other dishes from her cookbook’s “Family Favorites” menu: Hokey’s Roast Potatoes and Full-Color Fried Corn. We ate it on trays in the living room. She watched FOX News. I covertly binged House of Cards on my iPad. She was in her favorite comfy chair, the one where little girl me had curled up with Nancy Drew and an antique quilt a thousand winters ago.

“This is delicious!” my mother had exclaimed. A few stray kernels of corn escaped her fork. She did not notice. “Where did you get the recipe?”

By then she’d forgotten all about her cookbook, the newsletter she’d written and illustrated for thirty-two years, and, I’m certain, the peanut loaf.

V.

Gustaf Anders, a five-star restaurant, was run by a Swedish couple: Wilhelm Gustaf Magnuson, known to most only as “Chef” and his partner, Ulf Anders Strandberg. Before they retired and it closed for good, it was hailed as the finest Scandinavian restaurant in California, serving up such culinary delights as wild rice pancakes topped with smoked salmon and house-made lingonberry ice cream. The meatloaf recipe, faded and grease-splattered, was scrawled on the back of a menu featuring calves’ liver sautéed in herbs and jalapeños and venison with cloudberry relish. The meatloaf, known as “Monday Meatloaf,” was a weekly special so popular that people came at lunchtime not to miss it. It sold out most weeks and when John was able to sneak a few slices home, it was the perfect hangover remedy.

I ate there only once—it was pricy and I was just getting a foothold in what would become a decades-long sales career. I did not order the meatloaf.

VI.

After a long hiatus from the kitchen, induced by the decades-long jet-setting sales career that came to an abrupt halt when I returned home to care for my mother, I also returned to cooking. It began as a slow simmer; I had a household to run: care plans and car repairs, legal documents, a stack of unpaid bills. Making food was not on the menu.

Neither was becoming a mother at 50.

The first year, my mother cooked for me. After a dishtowel caught fire and the teakettle burned up, we cooked together, elbow-to-elbow in the tiny galley of a kitchen. Just as we’d done when she first taught me how to weave a lattice pie crust the summer before fourth grade, before my father left our family for another.

And when, like clocks and calendars, the words on recipe cards became a language she could no longer translate, I became the last cook standing. The transformation from daughter to mother was now complete.

VII.

My mother passed away during the pandemic. I inherited our old farmhouse and its antiques; its eccentric collections of toasters and typewriters; the recipe clippings and cookbooks she’d accumulated during the half-century she’d lived there; the big magic she’d made in the little kitchen. I inherited her words and her wit, sorrow and sea glass, her ghostly whispers of encouragement.

Into this space, I bring the things I have accumulated over a lifetime: the dozens of journals I’ve filled, running shoes and yoga mats, twenty-five years of sobriety, the meatloaf recipe. It’s journeyed with me through two divorces, two coasts and two careers—one that has ended and one just begun.

Into this space, I bring my words. Last in the lineage, preserving the family food writing legacy.

Amie’s Good Meatloaf[1]

COOK & TELL gets a kick out of being some distance from the cutting edge. But we must admit to a certain smugness when we find ourselves in front of, instead of behind, the New York Times. The issue of Cook & Telltouting this recipe had been in circulation for two weeks when the Sunday food pages of the Times turned up with four meat loaf recipes featured. Even the Times’ title, “Not Your Mother’s Meatloaf,” could have described Amie’s recipe—Amie is my daughter. Her recipe source was her stepbrother, who got it from a swank eatery where he worked. Daughter, then mother, made adjustments to this great meatloaf, with its pre-sautéed onion and built-in ketchup.

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 small onion, chopped (about ½ cup)

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 teaspoon dried thyme

1 ½ pounds ground beef

¼ cup fine, dry bread crumbs

1 large egg

¼ cup ketchup

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1 teaspoon soy sauce

½ - 1 teaspoon Tabasco sauce

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F.

Heat the oil in a large skillet over medium heat and sauté the onion and garlic until limp and translucent, about 5 minutes. Add the thyme and sauté for 1 minute more. Set aside to cool.

Combine the ground beef, bread crumbs, egg, ketchup, Worcestershire, soy sauce, Tabasco, salt and pepper in large bowl. Add the onion mixture and combine. Pack the beef mixture into a 1 1/2-quart glass loaf pan. Bake for 45 minutes or until the juices from a dainty slit made by a sharp knife are no longer pink. Let stand for 5 minutes, slice into slabs and serve.

[1] Bannister, Karyl. Cook & Tell: No-Fuss Recipes & Gourmet Surprises, Houghton Mifflin

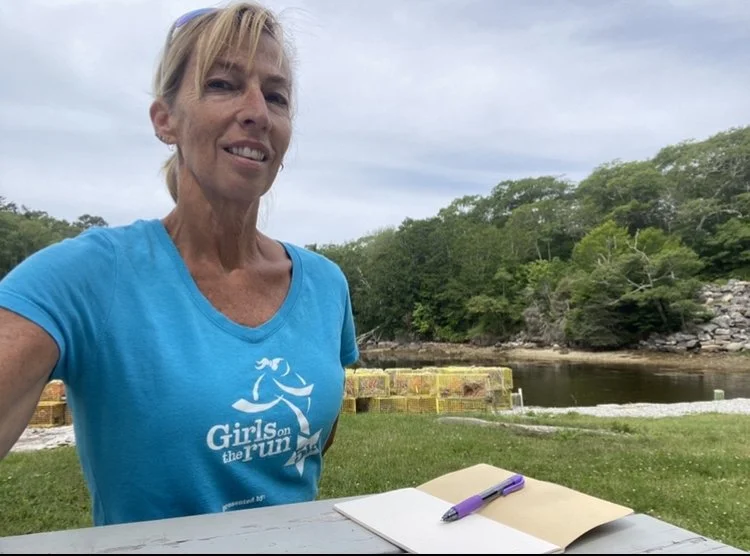

-Aime McGraham

Amie McGraham grew up on an island in Maine where she spends summers as curator of family ghosts and recipes. Winner of the 2022 Intrepid Times travel writing competition, Amie’s writing has appeared in anthologies and literary magazines including Brevity, Hypertext Review, Maine Magazine, Wild Roof Journal and Exposition Review. Her poem, lunaSea, was recently featured on Maine Public Radio. Amie produces the micro mashup, a weekly 100-word newsletter. And she’s currently cooking up new stories for Cook & Tell, a digital reboot of the foodletter her mother created 40 years ago, featuring vintage recipes, artwork and stories from a Maine island.