Mourning Sharon

I was chopping carrots to make soup when I returned the hospital social worker’s call about my patient, Sharon. I had made calls like this many times before. At 78, Sharon had multiple medical conditions and was often hospitalized for brief periods. But this time was different. The social worker said brusquely: “Your patient; she died today of Covid.” The knife in my hand dropped to the cutting board. I began to sob: deep, gulping sobs. In the five days since we’d last spoken, Sharon had died of Covid? How could that be? Through the dull roar in my head, I heard my 5-year-old whining and my teenager’s insistent voice in the hallway. I could not answer them. “How?” I kept asking the social worker. “How is that possible?”

Sharon was the first patient assigned to me on internship, a year before I completed my psychology doctorate. She had wiry, grey shoulder-length hair and piercing, blue-jean-colored eyes. In our first session I asked her if there was anyone who really understood her. She didn’t answer right away.

“No,” she eventually replied. “I don’t think anyone has ever really gotten me.” Then she wept.

We circled around that question for the next 19 years as I treated her in weekly individual therapy and group trauma treatment. I sat opposite her for so long that I memorized the veins on her hands. I would have recognized those hands anywhere.

“He’s like a piece of furniture,” she told the group about her second husband. “He’s just there, I should dust him when I dust the armoire.” She cackled.

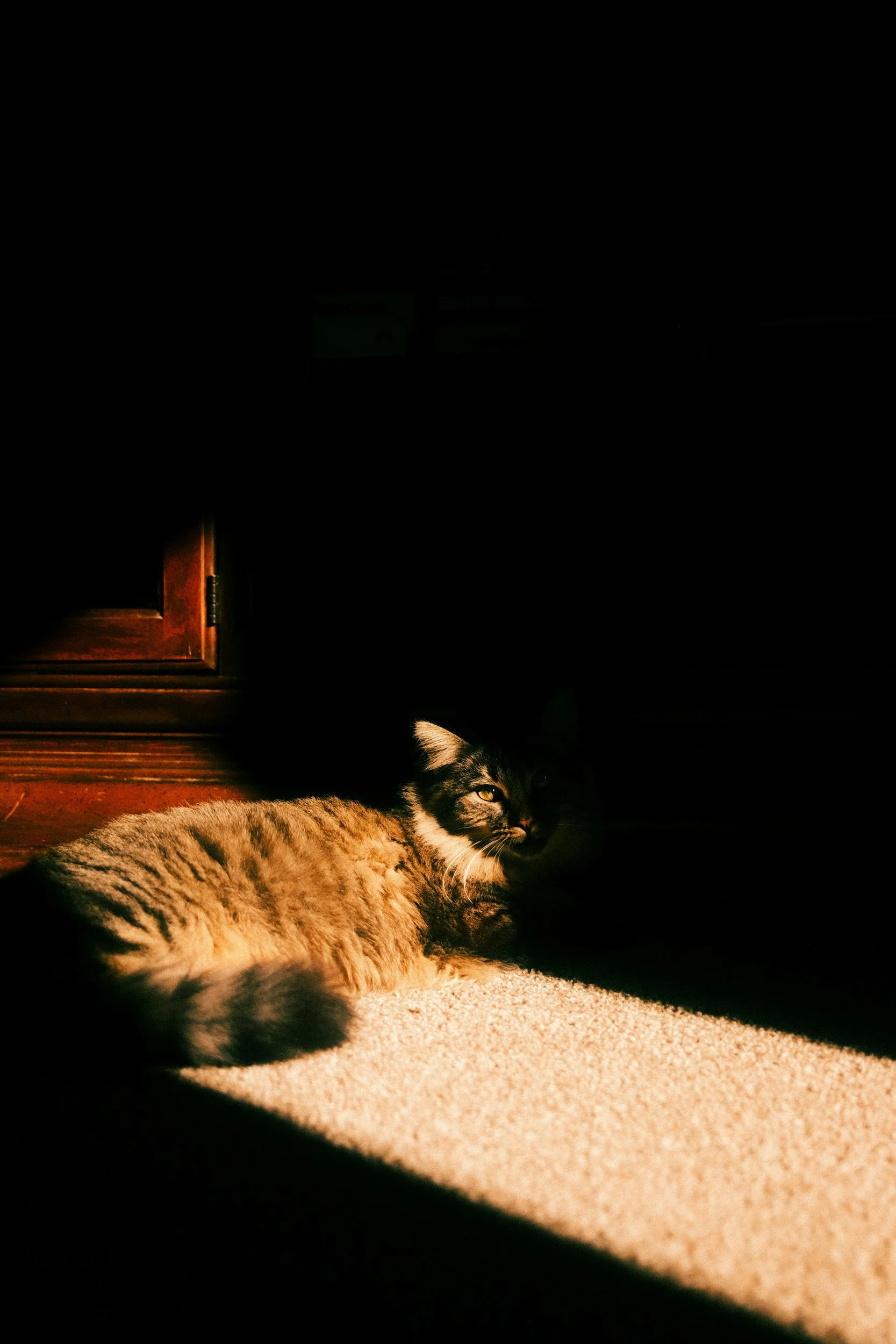

Her laughter was a like a sun shower: bright and infectious, with dark storm clouds circling underneath.

Sharon called me from the emergency room after her husband hit her, not for the first time.

“I’m done. I’m moving on from him now. I’m telling you, so you can hold me accountable.” Her voice was ragged and hoarse. I promised her that I would.

“Ok guys, who wants to ask me what happened?” she asked defiantly in group the next week. Her eyes sat atop half-moons of grey skin and her hair was pinned over the yellow bruise on one side of her forehead. Her husband had shoved her so hard against the refrigerator that she had fallen backwards, hitting her head and cracking three ribs. Nine women gazed down at their laps. I ached for Sharon as she picked at the loose threads on her shirt. “It’s ok, I’m from Texas. We always land on our feet.” She hated to be pitied.

As a young girl her mother was constantly telling her to cover her mouth when she smiled because her teeth were crooked. The one person who appreciated her vivacious spirit was her father. He bought her overalls, instilled in her a love of plants and the outdoors, and woke her up one night to see the full moon. He also sexually abused her from the age of 5 until she left Texas at 18. Nobody ever knew. It took years of therapy for her to admit that it was wrong. “I don’t know how to be angry at him,” she said. “ How do you hold anger for someone who was also the only person who ever showed you tenderness?”

Before she married (and divorced) a third time I told her it was time to revisit the sexual trauma.

“But why would I want to do that? I’m doing just fine without remembering all of that.” She couldn’t meet my eyes as she said this. I didn’t need to tell her that it wasn’t true, that marrying men who abused her meant that she wasn’t doing fine at all. She sighed heavily. In a small, tight voice she began to unwind the abuse, and to figure out when she knew it was wrong, a process that unfolded over many years.

“I wonder if he died regretting what he did to me? Did it ever occur to him, or was I just not that important?” Exiting the office that day, I blinked into the glare of the sunlight, all the colors and people rushing past too much after the stark intensity of what she had revealed.

A couple years later, she asked me, “Did you know in that first session what had happened to me?” I paused for a long moment.

“I think I did.” Perched on the edge of my seat, I was ready to explain but she quickly nodded. “I knew you did.”

I might have recognized certain patterns from work with previous incest survivors, but the truth is I just knew.

At times the therapy relationship is straightforward, the boundaries clear. With Sharon, from that first moment of intuition about her, it was different. She needed me, intensely at times, and I grew to love her. Some days after sitting with her I would go home and make dinner for my husband and pretend I still loved him. But I couldn’t ignore the contrast. The person who found tasks around the house to avoid conversation was a pale shadow of the person who, at work, dug so doggedly to find the truth about abuse. At first, the difference in the two versions of myself made me feel like a fraud. Ultimately, though, my relationship with Sharon helped me discover the version of myself I liked better.

Sharon found joy everywhere. She once found a stray cherry blossom branch with pink flowers on it outside my office and arranged it beautifully on my window ledge. Her face lit up when she described finding an entire set of Emily Dickens for only five dollars at a used bookstore. She loved stories, and patiently coaxed them out of the other patients in group. I knew she showed the same care talking to a stranger on the subway. People opened up to her because they felt her genuine interest. Sharon would often tell me tales of her postal carrier’s “remarkable recovery” from substance abuse. One time I asked her if she appreciated how remarkable it was that she, too, had been able to pick herself up after the childhood she had endured. She stared at me blankly for a long minute.

“No, I think I never thought I would live past 20. I just keep putting one foot in front of the other.” She was pensive. “So, it’s all a gift.”

“Sarah, you don’t look happy. Are you sure marriage agrees with you?” She asked me one day. She didn’t expect me to answer, but she was extraordinarily perceptive and rarely wrong. She predicted my divorce long before that relationship’s weary collapse and asked if I was pregnant before I had even allowed myself to take a test. Sometimes if I was not tuned in entirely to her, she would ask me “Are you fully here?” I knew better than to pretend. “You’re right, I wasn’t entirely, but now I’m back. I’m here.”

After my divorce it took me time to acclimate to the idea of myself as a single mom. I felt ashamed that I wasn’t ready to take my wedding ring off, but I knew I wasn’t. So, I bought myself a thick, silver, chunky ring, so different from my thin, gold wedding band. Sharon was my only patient to comment on the new ring, or to notice, with raised eyebrows, it’s removal after a full year. “Good for you, honey.” She pointed to my hand. Our eyes met, and I swallowed the lump in my throat.

She also knew instinctively that I would not want to be questioned when I had a miscarriage at five months. Instead, she wrote a poem about loss and mailed it to me, so I could read it privately.

One line tore at me: “I remember to breathe, I continue to rise, up where the sun, or the stars grace the sky.”

“Sometimes I just marvel at the world,” she told me in her thick Texas twang the day I returned to work.

“There’s just so much beauty in it. Every day I find something remarkable. So much heartbreak, but so much beauty.”

Leaving my office was always hard for her. She hated goodbyes. Eventually we developed a ritual: I stood up and stood by the door, opening it for her. “I’ll see you next time.” Every time she looked panicked. Then she would collect all her belongings, she always had at least three bags with her, and shuffle out.

In the long run, her unresolved traumas were a drumbeat that she never truly escaped. She longed for lasting connection, but rarely found it. The same indomitable, obstinate spirit that inspired her to leave Texas often curdled into rage. In the last year, the social isolation of Covid had made her angry outbursts much worse. Last month the social worker on the unit called me to make sure they could discharge her with a note that she still had psychiatric care. “Are you sure?” she asked me, as if disbelieving. I winced hearing this, understanding that Sharon’s anger had boiled over yet again. In the end, she pushed away nearly everyone in her life but me. Even the manager at the Apple Tree grocery who had extended her credit for decades stopped after an altercation over a bag of oranges.

My enduring imprint of her, though, is one of hope and vivid, irrepressible light. Her deep, throaty laugh was like the bud on a tree limb scorched by fire. I learned to calibrate my honesty with myself through the intensity of our relationship. I learned to look in my own relationships for the satisfaction of feeling “gotten,” a word I will forever associate with Sharon. Our work together helped me to both acknowledge my own broken parts and to notice and hold onto beauty. She saw life as a surprising gift. But, for me, she was the gift.

-Sarah Gundle

Sarah Gundle has a doctorate in Clinical Psychology and a master’s degree in International Affairs from Columbia University. In addition to her private practice, she teaches courses on trauma and international mental health at Mount Sinai. She is also a member of Physicians for Human Rights and works in their Asylum network, where she evaluates the mental health of persecution survivors seeking asylum. SarahgundlePsyD.com