The Road to Durango

My brother props his long legs on the dashboard of Dad’s pristine Honda. He presses his feet in their sweaty black socks into the windshield hard enough to leave `a smudge, a crime our eighty-five year-old father swoops on like a hawk.

“Make yourself comfortable, why don’t you, Billy,” snorts Dad, who’s already put in a three-hour drive from his home in Alamogordo to pick us up at the Albuquerque airport. His sarcasm is lost on Billy.

“Tired,” my brother mumbles. “Had to get up at five.”

Like the rest of us didn’t have to get up at the crack of dawn, too. Billy flew in from San Diego; I arrived from the Bay Area with Sadie, my eleven year-old daughter.

In the back seat, Sadie and I exchange smiles. She cups a hand over her mouth to stifle a giggle. Sadie adores her ‘Uncle Peanut,’ a teenage bad-boy trapped in a 50-year-old man’s body. He’s a spot-on mimic with a gift for telling family stories that bring us to tears. The one about him finding Dad, sprawled on his belly in a ditch near our home when we were kids, is one of Sadie’s favorites. Our father landed there after taking a spill on his new Kawasaki dirt bike, his latest toy. Sadie cracks up every time Billy reenacts the scene: Grandpa, red-faced and cursing. The motorcycle whining beside him, it’s still spinning tires peppering him with dust and gravel.

We’re cruising north on I-550, bound for Durango, the Colorado town where my sister, Betsy, and my mother live. My other brother and his girlfriend arrive tomorrow. I’m still trying to wrap my head around the fact that we’ll all be together under one roof again, something that hasn’t happened in more than 20 years. Such a gathering seemed unimaginable after my parents’ bitter divorce decades earlier.

Knowing that my father orchestrated this reunion, after reaching out to my mom to make amends last year, is equally mind-boggling. Age and sobriety have mellowed his dark moods. But I still remember the man I briefly lived with in a sad apartment complex in San Diego after their divorce. I was 19 at the time and hated coming home from a night of partying to find my father, sitting in the dark in his Lazy Boy recliner, drinking and plotting revenge on my mother.

“I’ll tell you what I’m gonna do, Dorothy,” he slurred one night, shrouded by a smelly cloak of cigarette smoke. “I’m gonna get a machine gun and blow that bitch and her boyfriend away.”

Even the though the room was hot and stuffy, I wrapped my elbows tight across my chest and shivered. I longed to flee to my bedroom but couldn’t make my legs work. Couldn’t believe the ghostly figure uttering these words was my father. When he wasn’t obsessing over killing my mother, he was threatening to kill himself. Sometimes, I wished he’d just shut up already and do it. I couldn’t handle the bombs he kept lobbing at me and moved out eight months later. Dad checked himself into a psychiatric hospital soon after.

Billy was diagnosed with bipolar disorder when he was 18. The way my mother tells it, mental illness snuck up on him almost overnight. One day he was surfing with his buddies, chasing girls and playing gigs with his band. The next, he was babbling about close encounters with Jesus, punching holes in walls and ranting—in dead earnestness—that he was the world’s greatest singer.

Our father taught him to play the guitar when he was six. Sometimes, I imagined Dad’s illness seeping from his long, graceful fingers into the instrument’s strings, then permeating my brother’s tiny hands, during the many hours they passed the guitar back and forth. Sadie was already diagnosed with early onset bipolar disorder by the time Dad started giving her lessons on the ukulele when she was seven. Maybe I shouldn’t have been shocked that she inherited the family curse at such a young age.

*

Billy stares out the window as we speed along the highway. I can tell he’s oblivious to the landscape I’ve come to love during my many visits to the Southwest: Coral-hued desert floor dotted with clumps of feathery sage. Bumpy green-flecked mountains rising in the distance. Chubby white clouds scooting across the turquoise summer sky. My brother’s brown eyes have a familiar look I dread. A look turned inward. It makes me think of a turntable needle stuck in a scratched record groove, playing the same angry or worried thoughts, over and over. It’s a look I’ve seen in my dad’s eyes. And in Sadie’s.

In Bernalillo, we stop at Starbucks. I order drinks while Sadie and Dad hit the bathrooms. Outside, Billy paces back and forth on the sidewalk. Scowling, he alternates between dragging on a cigarette and talking into the phone mashed to his ear. Sadie does the same thing—minus the phone and cigarette—when she’s hypo-manic, a milder form of full-blown mania. Paces our living room like a caged tiger, snapping her fingers and growling at me to take her to the park, the store, on a hike—somewhere, anywhere, right now—because her brain is attacking her, and she can’t possibly sit still.

I’m guessing the person on the other end of my brother’s phone is his girlfriend since it looks like he’s yelling. I hope we’re not in for another tirade about her jealousy, or how she gets so pissed off at him over nothing.

After our Starbucks run, Dad asks me to drive and slips into the front passenger seat. Billy scooches next to Sadie in the back. I ease the Honda onto the highway, braced for my brother to assault us with a volley of complaints about his girlfriend. But when I glance in the rearview mirror, I see his face soften as he turns to Sadie.

“So what meds are you on these days?” he asks, as casually as if he’s asking her about school.

“Abilify,” she says. “But I might go off it this summer.”

“Oh yeah? Not working anymore?”

“Not as good as it used to.”

“Sadie’s doing really well at her new school, so we’re starting to wean her off it,” I chime in. “See how she does without meds for a while.”

Billy nods. “Lithium really helped me. I don’t have nearly as many bad days as I used to.”

“I used to take Abilify,” says Dad. “And a bit of Adderall—gave me a nice little lift. I’ve tried every drug Big Pharma pushes!”

He chuckles and swivels around to grin at Sadie. She laughs at Grandpa’s warped joke. Billy smiles.

The conversation is as unreal as the mirage of water shimmering in the distance. It’s the first time my brother’s ever talked openly about his mental illness. This is not the guy who greeted me a couple of years ago at the seedy San Diego motel where he landed after his last girlfriend kicked him out. I was there to drive him to a psychiatrist’s appointment my mother made for him when she was trying to get him on disability.

“I’m not crazy!” he screamed at me, hurling a cup of coffee across the room.

Now, he calmly shares tips with Sadie about what to do if she has trouble sleeping.

“Try Ativan,” he advises. “I only take it in emergencies, like when I haven’t slept for a couple of days. But it works. Quiets the chatter in my head.”

Sadie nods. She knows all about chattering voices that keep you up at night.

I can’t imagine giving Ativan, an addictive sedative in the benzo family, to my 11-year-old. So far, Benadryl usually does the trick when Sadie’s too revved up to sleep. But I’ve been on this journey long enough to know I can’t say for sure I’d rule out Ativan—or anything else—to help her.

I flash to an afternoon a few summers ago when my father visited us in Marin. We stood under the big plum tree dripping with white blossoms in a corner of my backyard watching Sadie jump on the trampoline. Bouncing higher and higher, she finally descended cross-legged in the center of the black nylon circle, erupting in laughter that mingled with the trampoline’s squeaky song.

“Sadie seems a lot better than the last time I saw her,” Dad said, smiling at me. That was a couple of years before she started taking medication.

“Watch this, Grandpa!” Sadie chirped.

Dad clapped as she showed off her front flip. Then he lowered his voice and leaned closer to me.

“Did I ever tell you about the time my mother forced me to get electro- shock therapy? ”

My grandmother was a single parent with six kids, desperate to zap her only son’s violent, hellion ways right out of his head. I’d heard fragments of this story from my mom. But never the whole thing. Never from my father. Electro convulsive therapy, as it’s called now, was still relatively new back then, a more brutal version of the refined, effective treatment it is today. You didn’t count backwards and drift off to sleep, oblivious to the bone-rattling, brain-searing jolt of electricity coursing through your body. You were wide awake for the ordeal, strapped to a gurney, a couple of nurses on hand to hold you down when you convulsed.

Dad described waiting in line with a bunch of other troubled young men in a room at an Ohio hospital, hearing shrieks of agony from behind a curtained off area. Finally, it was his turn to step behind the curtain. He said the pain was excruciating. But it was nothing compared to the sickening realization that some patients didn’t shuffle back into the main room after their treatment. Some were whisked off to surgery for a lobotomy.

“No one told you if you were getting one,” whispered Dad. “They’d just roll you straight from the shock treatment area into the operating room. You woke up, and half your brain was gone.”

*

I pull my attention back to the road. Bernalillo’s bland string of tract homes gives way to miles of wide-open desert and flat-topped buttes. I can’t stop thinking about the meds chat, that this is my family’s reality. It kills me, sometimes, to think of Sadie’s future mirroring Dad’s or Billy’s. Their lives have been hard, marked by loss and more suffering than the average person must endure. I grip the steering wheel tighter, reminding myself, as I have a million times before, that catching and treating Sadie’s illness early is the best way to help her avoid their struggles.

An hour later, we reach the dusty village of Cuba. I slow the car as we pass a handful of fast-food restaurants, motels and convenience stores. A scruffy stray dog zigzags along the edge of the road, searching for scraps of food. Or maybe his pack. I’m keenly aware that I’m the only one in the car who doesn’t have an official psychiatric diagnosis or a prescription for meds. But as we leave Cuba behind, it hits me: I haven’t completely escaped the family curse. I wasn’t much older than Sadie when I started self- medicating the anxiety that bound me like a strait jacket. Perhaps I would have avoided my detour into alcoholism if my parents—preoccupied, by then, with their crumbling marriage and Dad’s illness—realized I needed help.

My thoughts drift to one of my earliest encounters with alcohol at a high school football game when I was 14. Under a full, shimmering moon, I stood with my best friend, Leah, behind the chain-link fence surrounding the stadium. We chugged whiskey from an Herbal Essences shampoo bottle passed to us by a popular surfer. It burned going down and tasted like soap. I gagged on that first sip. But then the whiskey settled in my belly. A warm glow tingled in my veins. The awkwardness and discomfort I hadn’t realized, until that moment, had weighed me down my whole life melted away. I felt light, giddy. Free. The invisible wallflower morphed into a vivacious homecoming queen, gabbing to the cute surfer I’d never have the nerve to utter a word to if I was sober.

Time took on a magical quality, simultaneously speeding up and slowing down. Without knowing how it happened, I found myself in the arms of a blurry-faced junior lingering in the shadows of the bleachers, his silver braces glinting in the moonlight. I had no idea what happened to the surfer. Or Leah. I didn’t care.

In what felt like minutes later but was actually hours past my 11:30 curfew, I lay shivering on some kind of cold, hard slab. The harsh glare of fluorescent lights pried my eyes open. Muffled voices I didn’t recognize floated above me. I was in the ER, one of the voices said. My head throbbed like never before. My throat felt raw. This, I would later learn, was from the tube a doctor crammed down it to pump the excess alcohol that had almost poisoned me out of my stomach.

My parents grounded me for a week and took me to a psychiatrist. During our one and only session, I bluffed my way through his questions. It was way too easy to convince him and my parents that I was a normal, well-adjusted teen who’d just had a temporary lapse of judgment.

Picking up where I’d left off, I drank until I passed out almost every weekend during high school. I came to on golf courses, in cars, and in stranger’s backyards with boys I didn’t know, baffled and humiliated.

Monday mornings, I’d slink back to school with a belly full of shame. I felt like I was heading for the electric chair as I walked down the hallways between classes. Eyes glued to the ground, I clutched my books to my chest like a shield.

As my list of drunken escapades grew, my already fragile self-esteem nose-dived. Too mortified to stand in front of classmates who’d witnessed or heard of my antics, I refused to give required oral reports or participate in class discussions. The perfect grades I’d always prided myself on started to slip. After graduation, my friends headed off to college. I took a full-time waitressing job at a retirement home a few blocks from our high school. And got my first DUI just before my eighteenth birthday.

*

Finally, we approach the outskirts of Durango, catching glimpses of the Animas River, lolling like a fat green snake in the late afternoon sun. Dad drives to his motel right down the street from my mother’s house after dropping us off. He returns for dinner an hour later. Sadie and I sit at the dining table, sipping bubble water and watching Steller’s jays and robins feast at the birdfeeder dangling from an aspen tree in the backyard. It’s surreal to hear my parents making small talk in the kitchen behind us.

“How was your drive?” my mother asks while chopping vegetables for a salad.

“Not too bad—hit some traffic around Farmington.”

My sister Betsy arrives with boxes of pizza. We help ourselves to slices and the salad Mom placed on the kitchen counter.

“You bring a guitar, Dad?” Billy asks, as we finish eating.

“Of course!” my father replies. “Brought one for you, too. And a ukulele for

Sadie. Help me get them out of the car.”

After they return, we all settle in the living room. Dad breaks into Jimmy Buffet’s

“Margaritaville,” Billy follows his lead. Mom hums along, tapping her thigh. Squeezed into a big easy chair next to Betsy, Sadie plucks at the uke. My singing is godawful, but I join in too.

Gazing out the tall windows, I watch the sun dip behind the burnt-orange ridge of the San Juans, infusing the sky with a warm peach glow. Then I glance around the room at my family. I’m used to thinking of mental illness as something that tore us apart. Yet here we are, enjoying the creative gifts that are as much a part of the family legacy as the suffering. Sharing a Kumbaya moment in my mother’s house, of all places. The healing didn’t happen overnight. But slowly, we’re finding a way to live in harmony.

The concert continues with tunes from Johnny Cash, Arlo Guthrie, Elvis. As the light fades outside, I can tell the long drive is catching up with my father. His face is pale, his fingers work the guitar with a bit less gusto. Billy notices too.

“Tired, Dad?” he asks.

My father nods. “One more song, son.”

He strums the opening chords to John Lennon’s “Imagine,” one of his favorites. His voice, like gravel rolled in honey, falters at first. But it grows stronger, buoyed by Billy’s deep baritone. Sadie’s pure soprano sweetens the melody. The rest of us join in.

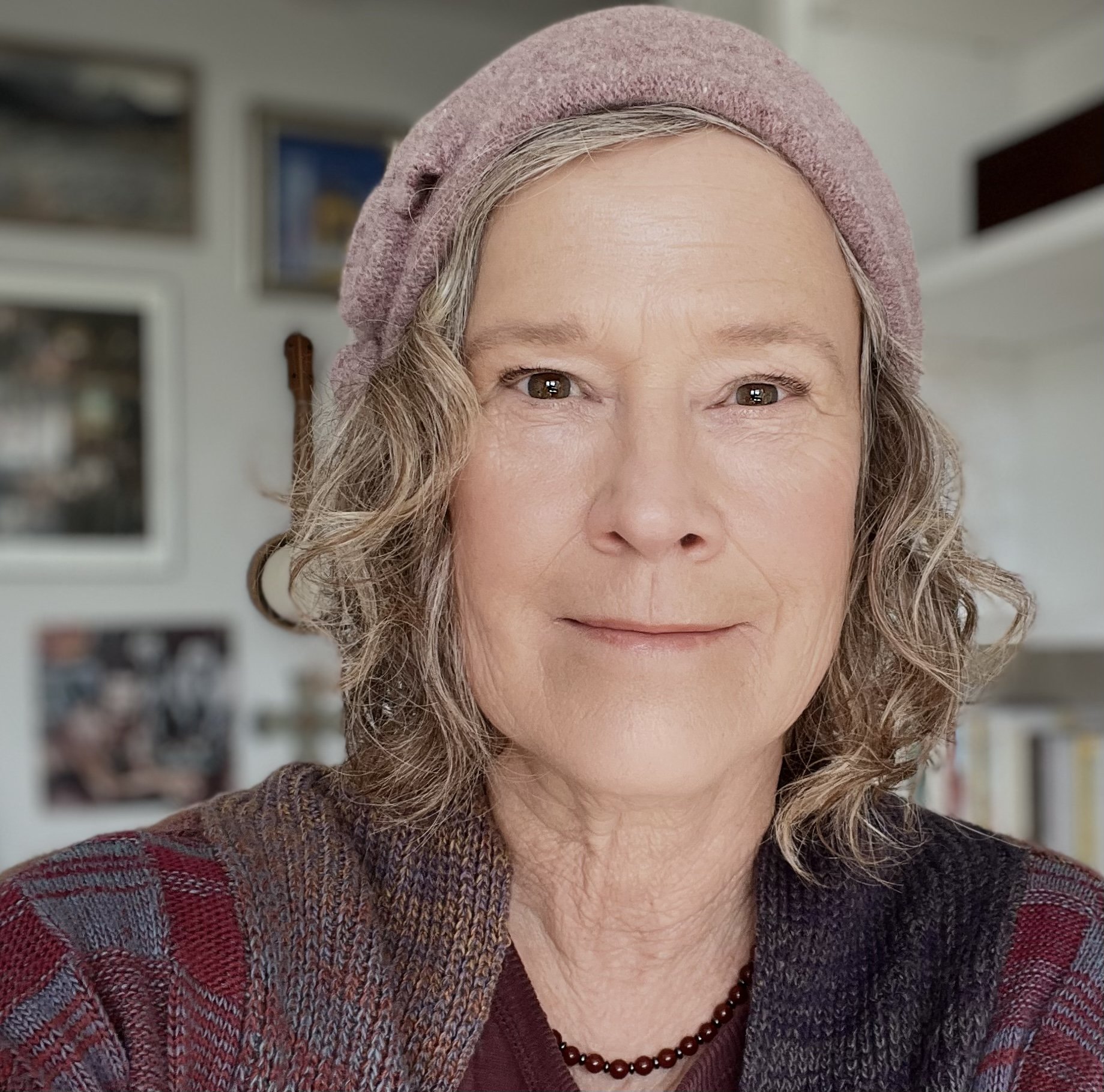

-Dorothy O’donnell

Dorothy O’Donnell is a writer based in San Francisco. Her articles and essays have been published by the Los Angeles Times, Great Schools, Scary Mommy, Salon and other outlets. She is working on a memoir about raising a young child diagnosed with early onset bipolar disorder.