The Episodes

And to feel that the light is a rabbit-light,

In which everything is meant for you

And nothing need be explained;

Then there is nothing to think of. It comes of itself;

And east rushes west and west rushes down,

No matter. The grass is full

And full of yourself. The trees around are for you,

The whole of the wideness of night is for you,

A self that touches all edges.

–Wallace Stevens, A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts

All sorrow takes me to the one place: my mother’s bedroom where she died in the night. When I return to the room, in my mind’s eye, I look out of the window and see my child self sitting in the grass, still as a rabbit. During the journey back, I witness how parts of me are scattered across time and space. When I arrive, the night falls around me, blurring my edges as in a vignette.

When my mother is still alive, I hide inside the room when the fights start between her and my father. I spend the day there, standing in front of the dressing table. There’s me: a small child reflected in the mirror. Sometimes my sister is there too. Through the closed doors, I can hear the rising cadence and energetic shifts in the fighting, voices getting louder and then quiet, the shatter and splinter of objects being broken. Sometimes it goes on for hours. I can remember the feeling of tightness in my small child chest, the racing thoughts and fears in my small child mind. Will my mother leave as she always promises?

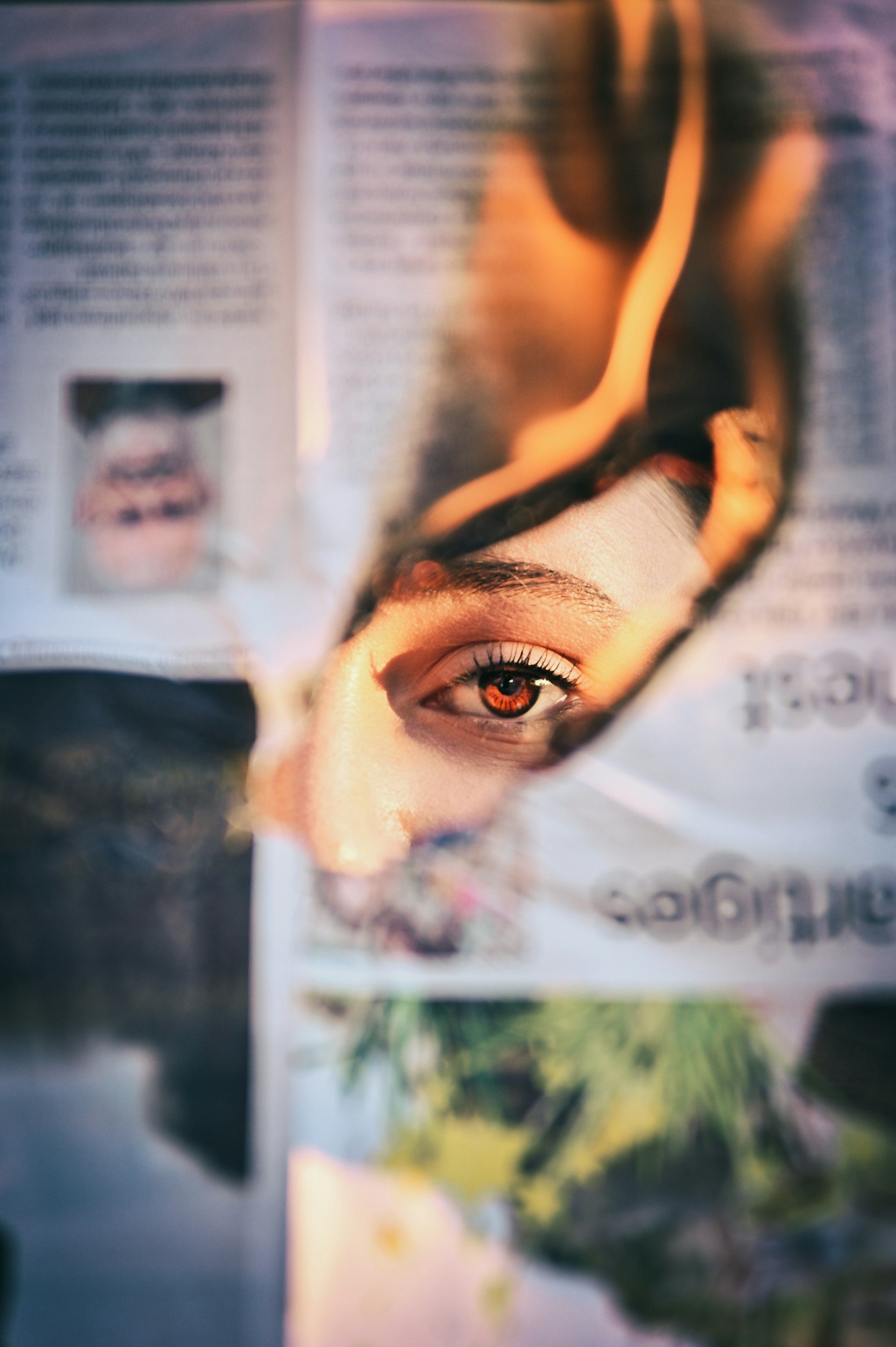

There’s a mirror on top of the dressing table that has three parts: a central mirror and winged mirrors on either side that swing in and out. I imagine my troubled mother glancing at the triplicate versions of herself, the three selves in the looking glass. She applies the red lipstick in the center mirror, leaning forward on tiptoes in order to reach. The mirror reflects the unkind effects of time, the changes to her womanhood. The softness of her has been cut away, diminished with the scalpel, first the womb, then the breast that contained the cancer.

My mother looks at her body in the left mirror; she places her hand over her swollen belly. She imagines the movement of life once there, a quickening that has now grown still, no longer to be. Unable to walk into the mirror and disappear altogether, she walks to the bedside table where she takes the first blue pill of the day.

My mother tells me frightening stories so I will stay away from her, so I won’t go to her in the way a child naturally goes to their mother. She tells me there’s something dead inside her that she still carries. She tells me she’s a witch and that’s why there’s always the black cat sitting on the roof of the house over the road you can see from her bedroom window. When I tell her that I told the girls at school she was a witch, she slaps me across the face for telling lies.

The blue pills live on the nightstand next to the bed. It’s her side of the bed for the time being, since my father still sleeps on the other side, before he rents a space in the beds of other women and stops coming home altogether. The bedroom gets rearranged in time to reflect the demise of the marriage.

Next to the blue pills, prescribed by the doctor for my mother’s nerves—for “the episodes”—is the un-drunk cup of tea I take to her each morning. The tea turns cold in the darkness of the room while my mother remains asleep. Early on, before he gives up on her completely, my father goes into the bedroom and drags the curtains open. They swing against the edge of the mirror; dust flies from them and travels, suspended, into the light of the day.

My mother’s moods are the weather inside the house. The barometer in the hallway by the front door gauges the elements—how much alcohol my mother has had to drink, how late my father has come home—and forecasts the imminent turbulence. I check whether the mercury inside the barometer has risen or fallen. When the fights get bad, the east winds strengthen to gale force.

My mother’s disposition is mercurial and tornadic, volatile and unstable. When the episodes play out, her quicksilver moods turn the sky green and the house dark black blue. I have to find shelter when my mother’s temper—fueled by pain disguised as anger, hurt hidden in the rage—begins to gather its own momentum.

My hiding place is inside the pitch black cupboard under the stairs. I hate to go there but I have to choose between one fear and another. The cupboard has dimensions of darkness that I can at least quantify, unlike my mother’s episodes that occupy a wider, dizzyingly infinite space. Objects fly in slow motion through the space in the direction of my father or just towards the walls that close in on her. The episodes are predicated on my mother’s need to escape herself.

Inside the cupboard, I enshroud myself with shame, with unlovability. It’s the hurt I will carry forward in time.

When I return to the past, I understand that the episodes also arise from an infinitesimal space, a tiny place: the pain and disappointment in my mother’s heart.

Sometimes the episode turns staccato. A single light bulb hangs, flickering, in an abandoned room. There’s a bed with the sheet torn off; there’s a stained bare mattress. I run.

I can only remember the turbulence of the childhood house in pieces; fragments of time have disintegrated into blackness, into the fugue. Deep inside the memories, the lights flicker on and off. There’s the flash of dark blood words, the slamming, breaking, and throwing of plates and glasses, my mother’s face contorted in rage.

I try to put the scenes in order, but they disintegrate into pixelated pieces of lost time.

I relive the scenes of childhood in all the times I leave myself to time travel. Often, with my notebook but sometimes, like my mother, I leave via the blackout, the loss of consciousness you can reach with alcohol. But I’m careful to respect my own love of numbness and so don’t go there very often.

In childhood, I always dread Sundays the most for they are the bad days for my mother, when I absorb the badness from her. The windows in the kitchen are clouded with condensed steam. You can’t see out. The potatoes and cabbage are boiling; the meat cooks in misery inside the oven. The Sunday meal is always prepared with bitterness, never with love.

It’s unclear how my mother’s moods go inside me on Sundays. Perhaps she offers them to me or I just try to accept them from her so we can have a nice day. It’s when I run outside and refuse to come in. A temper tantrum ensues. I’m dragged back in, kicking and screaming, and forced to sit down at the table in silence. The plate is slammed in front of me.

When I have the tantrums, it’s my body that betrays the family’s secrets: my mother’s addiction to the blue pills, my father’s indiscretions; the alcohol hidden in the cupboards, the swinging tumultuous insanity of the arguments. It’s their volatility that goes through me, not my own. Sometimes, there’s a display of prideful outrage about my outbursts, in which my mother and father quietly shame me about my own conduct. I know that they are circumventing the order of things, rearranging the natural rhythm of cause and effect. At the youngest age of six or seven, I establish a belief in my own innocence.

One Sunday, in a memory that remains unbroken, I’m sitting outside in the small piece of grass. You can see me from the window in my mother’s bedroom. I’m five or six. It’s calm and I can manage myself there. A fir tree casts a sheltering shadow over the grass. From the back of the garden, the tall lime tree stretches its protective branches into the pink sky above me.

For once, my mother opts for a decision of kindness and allows me to stay outside. Instead of ordering me back inside the house, screaming bloody murder, she grants me permission to miss the entire macabre spectacle of the Sunday meal. After a bit, she brings me a sandwich of brown bread and honey, carefully cut into four equal squares on a small blue plate. The bread was soft, the butter was cold and hard, and the honey was sweet. It felt magical to eat in the grass. I nibbled at the edges of the bread, wanting the experience to go on forever. It was dinner for a fairy; a fairy-tale dinner for one. The sandwich had been made with love. Everything was meant for me.

Looking back, I see my mother’s kindness; I see how I was fully present in that moment, possessing a self that touched all edges of my body. When I return to the memory, when I see myself sitting in the grass like a rabbit, I attach a music score to the episode. It’s the music from the New World Symphony written by the Czech composer Antonin Dvorak. The piece is both an antidote to and evocation of the nostalgia and desolation of time now gone by. The music tells the story of once upon a time, the notes convey the heartache, the hurt of longing and despair, that you feel when you try, even if it was traumatic, to attach yourself to something that is now gone.

When I return to the memory of once upon a time, I retrieve the memory as proof of the love I was able to absorb from my mother, the love she was able to give. There was nothing else to think of, nothing needed to be explained. It’s the place I go to when the sorrow turns my mind dark, when I need to connect to my mother as my ancestor, someone I can go to. It’s how I unchain the ghosts of my mother and me.

When I go back, I also return to comfort and rescue the exiled part of me, the one who holds the hurt. She’s the abandoned child version of me. In my mind’s eye, I sit next to her in the grass. I spend time with her because although she holds the hurt, she also holds my heart.

When I come home to the present, I bring her along with me, on a bright and cheerful journey through time. Her small hand fits perfectly inside mine. Sometimes we sit together on a train, with our feet on the seat in front of us. Her feet can hardly reach which makes us smile. She sits by the window, gazing out at vivid green landscapes, misty blue mountains. I wrap a blanket around her. We nibble imaginary sandwiches and watch the world together.

-Sarah Harley

Sarah Harley is originally from the U.K. and currently works as a teacher at Milwaukee High School of the Arts. She is dedicated to supporting her refugee students and helping them tell their own stories. Sarah's work has been published in Halfway Down the Stairs and elsewhere.