Forty-One Days of Mourning

My pale, Nordic friend, Dahlia, arrives on the station platform in Goa in late afternoon. We embrace each other in the brilliant sun, surprised to see each other in this place. I hold her trim, wiry body tight against me, surprised she’s really here.

“You’ve cut your hair,” I say, touching her blonde, butch buzz.

“And you’re tan! I’m going to catch flame in this country.”

She is the sort of western tourist who my Indian friend, Deepthi, would affectionately call a vampire. Even Dahlia’s eyelashes are transparent.

Like me, she had shown the address of the resort to her compartment neighbors, two older women in carefully pleated saris, and they had nudged her off the train at the correct stop into the sun, sand, heat, and colorful decay of Goa. We tourists amble into the backseat of an auto, and our driver zooms down narrow roads past Portuguese-influenced architecture. The houses and churches are Pepto-Bismol pink, Grecian blue, and brilliant purple. We drive past empty fields and two shirtless, languid European boys.

“Where are you taking me?” asks Dahlia, unlooping her arm from mine, the heat making our skin stick.

“A friend’s friend’s friend’s resort.”

Dahlia is in the country for a business meeting, and I have been living here for several months training as an ESL teacher. But I am on grief leave, fresh back from my friend’s funeral in the States. After the death of my close friend and mentor, Iris, the superintendent at the ESL school where I study in Kerala, India, allowed me to take several days off. My students tell me it will take forty-one days to fully mourn; I can’t imagine I will ever stop.

In the auto, Dahlia tells me about her week in Delhi and asks about life in Kerala, the students, what’s teaching like, how is the food different from northern India, and finally, “How are you doing with Iris’s death?”

I tell her how I stayed in Bangalore with friends for a few days. “My Indian mother, Deepthi, fed me and then put me on a train to Mumbai to learn every possible method of marijuana ingestion from friends of her brother-in-law. She told me I needed sensory grounding and that the chaos of the city would heal me.”

“Did it work?” asks Dahlia.

I shake my head.

As the auto driver pulls up to the entrance of the resort, I explain to Dahlia that Indian society functions on the four-handshake rule, meaning that friends of friends of friends let me, a pansexual American tourist, sleep on their floor, eat their food, drink their beer, and hang my thongs to dry in the heat of their notorious bachelor pad.

After a few days of debauchery and crying, these Bombay brothers planned the rest of my grief leave. Their aggressive hospitality was irresistible. In a moment of lucidity, their leader cried to me through the smoke, “You must see Goa! We will arrange everything. My friend has a resort in Panjim. It is fate you missed your other train! God must have something for you.”

At the resort, an employee takes Dahlia’s suitcase to my temporary beach hut home. I give a socialist flinch as another employee picks up my shabby orange backpack.

As we walk down the sandy path towards the sound of the waves, I tell Dahlia I am still adjusting to the tireless attentions of the serving class. “I wasn’t planning on a vacation. I just needed some time to decompress from the funeral.” All I have with me are partially clean clothes and a copy of C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed.

When I arrived the day before, the concierge had asked if I traveled alone. I’m used to the question. It’s not just my age and gender that make independence an aberration of behavior. To desire solitude is an unfamiliar concept in India.

I unlock the beach hut and flick the lights. “Power’s out. No worries. There’s only one bed. Hope you don’t mind.”

“As long as you don’t kick or drool.”

“Can’t make any promises.”

While Dahlia’s in the bathroom, I change into shorts in the dim light. Having been living in conservative Kerala, I feel odd showing my legs. I remove what the Bombay brothers called my “jewelry store collection:” bangles, rings, and long earrings that touch my shoulders. I unhook my cross, a gift from my catholic students, who upon hearing I couldn’t sleep for sadness, gave me the pendant to help ease my pain and my friend’s possible state of purgatory.

“I’m outside!” I call to Dahlia.

I head out into the sun with a towel, a book, and my old-fashioned flip phone. I pick a lounge chair and try not to think about how much Iris loved to be near water. Alone on the beach, I am afraid to be still. Grief, C.S. Lewis writes, feels like fear because so much of my thought life was devoted to Iris, and in her absence, I feel the anxiety of frustrated impulses. Silence presses on me. Waves of sadness rise to my nose, threaten to submerge my body. I need to move before bereavement debilitates me. My Indian mother calls.

“Hello darlink,” I answer, relieved by the distraction.

“How do you like the place? Is it ok? Did your friend arrive yet?”

“Yes, she’s freshening up. The place is gorgeous and practically empty. Wait, I see one beach bunny.”

“Foreigner? You should go make friends.” Deepthi is always telling me to do this.

“I will,” I say, “just for you, if she speaks English. Because not all white people speak English.”

“Whatever, you’re all the same to me.”

“You’re just jealous, sitting at home with nothing to do. I’m going to go pursue hedonism, without you!” I blow an affectionate raspberry and hang up.

My only neighbors are the one tourist and an attendant waiting to indulge all of our alcoholic whims. The young employee lounges under an umbrella listening to Marathi news.

I stare at the water. The effort of not thinking about Iris brings on the exhaustion of the deeply ill. I wish I could throw up and recover.

After Dahlia unpacks, she appears in the beach chair beside me. She orders her first drink, and we fall into casual conversation, our faces pressed against hot plastic beach chairs. While the landscape of India is decorated with billboards for skin-lightening cream, we foreigners have the opposite infatuation. Wanting what we don’t have, we crisp ourselves to the color of burnt toast.

My friend lounges in a black two piece, smothering herself with lotion. She asks, “You don’t have a bathing suit?”

I explain that I’ve been trying not to embarrass my conservative friends with any wily Western exposure of skin and didn’t even bring a bathing suit into the country.

After a few martinis, we head for a walk to burn off her train journey. In late spring, it’s too warm to wear much, and for the first time I feel uncomfortable with the stares of the locals. Dahlia doesn’t seem to notice.

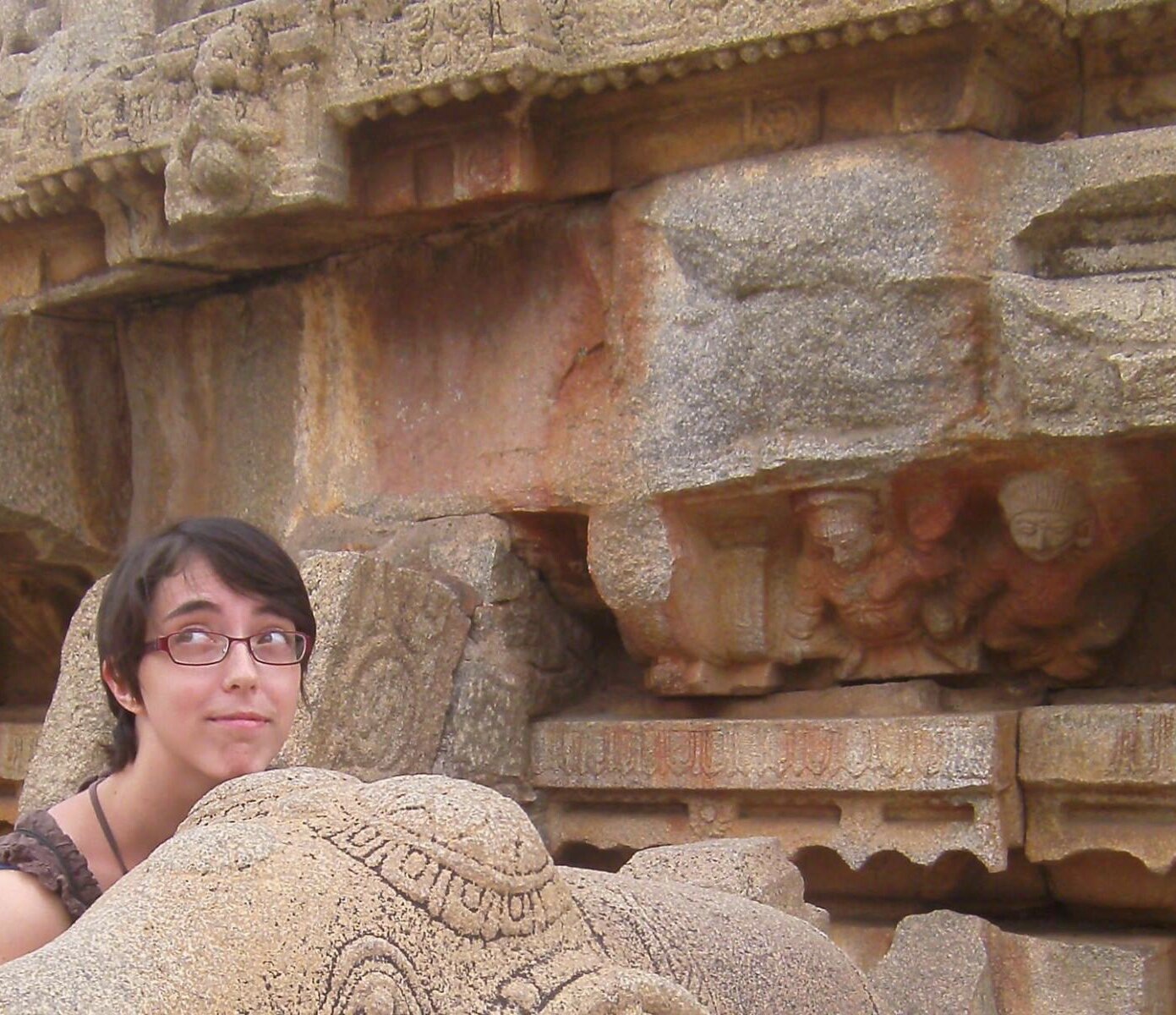

We rent a motorbike and bounce through Goa. Dahlia stops at holy places for Catholic and Hindu believers. The two religions seem to have mixed together, and Mary gets her own shrine. We stand in the quiet, cool space of an empty cathedral to consider deities, sins, and sanctification.

I whisper, “Why is Christ white?”

We were both raised in the church and have ambivalent feelings towards the religion as we’ve grown older.

“Wait,” she takes my hand. “Maybe if we stand here long enough God will show up.” We wait in silence. “Do you feel anything?”

“It’s the architecture,” I say. With detached brevity and a lack of personal adjectives, I confess my disillusionment with Christianity following Iris’s death. “I feel like I’ve fallen out of love with Christianity. The answers it provides aren’t feeding me at the moment.”

She nods. “I’m always amazed at people who can take the bible whole. I haven’t decided if it’s blind stupidity or inspiring faith.”

Dahlia and I exchange insecurities, balancing the scales of personal disclosure, but she doesn’t say much. Instead, she offers me a hug under the figure of an effeminate blond Christ, touching ear to ear, pelvis to pelvis. We take a seat on a pew in silence, bare feet cooling on the floor.

She says, “I’ve never loved like you have. I mean, not anyone I could keep or take home to my parents.”

I realize she thinks Iris was a lover, as if my deep grief can only be explained by sexual attraction. Before I can correct her, she says, “I’ve been struggling with bisexuality for years, but I’ve never told my parents.”

I blink and take this in. “Even now as an adult you can’t talk to them?”

“They’re ultra conservative. It would be painful for them.”

“You keep your relationships secret?”

She looks at the altar, the stained glass. “It’s not hard.”

“You’ve never talked to your family about the women you’ve loved?” I am baffled.

“I’ve never been with a woman.”

In the awkward pause that follows, I try to process how I could have missed this core part of her personality and why, even knowing that I was out, she would keep this a secret for so long. I feel a touch of sadness for what she has missed.

She says, “Besides, I’ve never felt comfortable with labels. Some of my friends think that it means I’ve been too hurt or psychologically damaged to accept men. Have you heard that reasoning?”

Yes, I nod. Having grown up in a rural community, I had heard all of it.

She goes on. “The idea of being born this way doesn’t work for many people in my family. And I haven’t found a solid way to reconcile sexual impulse with my religion.”

A growl from my stomach interrupts her train of thought, so we head back to the hotel restaurant. We pick a table with a view of the water, and order shrimp biryani and cocktails. Over dinner, she admits to having a crush on me for the last decade.

“I find you attractive as well,” I stammer.

Dahlia moves her chair closer and touches my hand. She looks at my mouth when I’m talking and takes opportunities to rest her hand on my knee, touch my shoulder, hair. She is hesitant. This growing attraction seems to terrify her.

We eat with our fingers off each other’s plates and sip rum and coke. I’m frank about my ideas on holiness, feminism, and how faith and sexuality can coexist. Dahlia is guarded, holding personal information away from me. Dancing does us in, and our lips touch; I wait for her to move or follow my lead. Our teeth knock on the second take.

“Sorry, I’m not much of a kisser,” she says.

“Don’t apologize.”

Dahlia’s flustered, “Can we…do you want to go to your room for a drink?”

My brain tells me she is an old friend and this will be a mistake. But we are both sloshed, and I am emotionally exhausted. I want a distraction from crying, from the silence in my head left by Iris’s absence.

Why the hell not?

I take her hand and lead her back to our beach hut. We leave our flip-flops at the door and draw the bamboo blinds. She sits on the bed and starts to take off her clunky jewelry, but her hands are shaking. I stand in front of her, unlock the clasp of her necklace, and kiss her neck. I kneel to kiss her wrist, moving my lips to her hand, folding her knuckles to my mouth, and then ending with a bite to her fingertips.

In the morning the electricity shuts off again, and the heat of southern India wakes me. I’m alone and a little disappointed. Dahlia has left behind the smell of her perfume in my hair and in the crook of my elbow. My next thought is the horrifying awareness that Iris is still dead. I move. I wash Dahlia off under the cold spigot with the two-bucket method and then pull the sheets off the bed when there’s a knock at the door.

“Oh,” I answer. Dahlia’s holding a tray of fruit and tea.

I clean off the table. She’s wearing makeup today. “Are you smiling?” I ask. “Is that a dimple?” I poke my finger in one, giggling.

For the next few days we dance and glow in each other’s company. In public we touch easily, like Indian women, holding hands, teasing. With me, she is lazy and joyful, collapsing with laughter at every opportunity. I am relieved to find someone who can so thoroughly remove me from grief. I feel my heart shift from thinking of her as a friend to thinking of her as a lover.

As my official days of mourning come to an end, and it is time for me to head back to Kerala and my studies, Deepthi leaves more messages. “I’m calling to eat your brain. How are you doing? You must be bored by now. We are missing you. Even the dog is missing you.”

On my last morning with Dahlia, we wake early and sit on sand the color of gingerbread to watch the sky change. The locals sleep less than we do and are already out with fishing nets and boats. Dahlia shivers into me, pulling part of my scarf and wrapping it around her shoulders. We rest in the quiet, our eyes stretching out to the horizon, the Arabian Sea a flat line against the sky. Later, we have breakfast on the beach hut porch: fruit, idli, and masala tea.

We tourists pack in the morning light. After a week of swimming, we’ve left a trail of sand across the white tile floor, from the threshold to the bathroom.

“I hope you don’t take this the wrong way, but we really can’t tell anyone about this,” says Dahlia. “I might be ready to come out to my parents eventually though. Thanks for helping me with that.”

“What?” I turn from cramming clothes into my backpack.

“I couldn’t come out until I had sex with a woman, to know if it was real, you know? Now I can tell them someday that it really is part of me.” She beams with this revelation.

I stare at her. “This was a way for you to collect evidence for your parents? Why do you even need to justify yourself? You’re thirty fucking years old.” I feel my face flame. A migraine blooms in my brain.

“Why are you getting upset?”

I am out of air, gasping. “Because sex changes things, and our friendship is changed, and now you want to pretend it didn’t happen. I’m here to mourn, and you used my body to try on an identity.”

I sit on the bed, and she kneels in front of me, taking my hand.

“I’m sorry,” she says, placating. “But I didn’t do anything wrong. It was important for me to find out. You have no idea what this would do to my parents. I can’t take you home as my girlfriend. This would hurt them.”

I slow breath back into my body and wait until I have words other than “fuck you.” Instead I say, “Be who you are or ask your version of God to change you. If you can’t do that, you should have stayed the fuck out of my bed.”

She takes a breath like I’ve snapped her in half. She stands and walks out. An hour later, I check out, thanking the owner for his generosity, and then I ride to the airport with Dahlia in silence. We do not touch, inconsolable in our disappointments. We stare out the windows at the Portuguese-influenced architecture with our arms crossed and eyes bloodshot. We have the rest of the day to brood and overanalyze the details of our argument.

She leans in to kiss me, and I turn my face away.

I catch a bus that will take me south to Kerala and curl into my window seat to sniff the crook of my arm for snatches of Dahlia’s perfume. My seat neighbor, a young, catholic researcher based in Mumbai, offers me her flashlight so I can keep reading C.S. Lewis as the sun goes down.

We chat about her studies on monkeys, and then she asks about my book.

“Death is hard,” says my neighbor. “We never really get over loss. I don’t mean to pry, but perhaps you’ve found God in Goa?” She nods towards my cross.

I take a deep breath, “It’s not as if God’s been hiding. I just don’t know how to hear her.”

“You are probably just talking too much. He won’t shout over you.”

I give a noncommittal smile and turn back to my book.

-K. Bell

K. Bell often writes about trauma and healing. Her work has appeared in journals such as Hotel Amerika and Verity La and was the recipient of Crab Orchard Review’s John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize.