The Sign

It was a perfect August day, and the Wolf River was clear and cool. The leaf canopy of spruce and cottonwood sparkled overhead, like shards of brilliant green glass backlit by intermittent bursts of sunlight.

Dave and I were trying out the twin red kayaks that his kids had given us the previous Christmas. Everyone agreed we had been working too hard, and the weight of a business we could no longer save was taking its toll.

We had been together eleven years. The day after my Chicago newspaper career fell victim to the Internet, I joined him in the Northland. Dave was dismantling the world’s biggest grain elevator, reclaiming a forest of old-growth wood, and I became his chief enabling officer. What’s mine is yours; no questions asked. Even when the recession made his business plan look like pie in the sky.

On the water, as in life, Dave led the way. I followed his confident path downriver, my mind blank as I dipped the paddle into the water—right, left, right again—feeling only the warmth of the sun on my forearms and the incipient blisters on my palms.

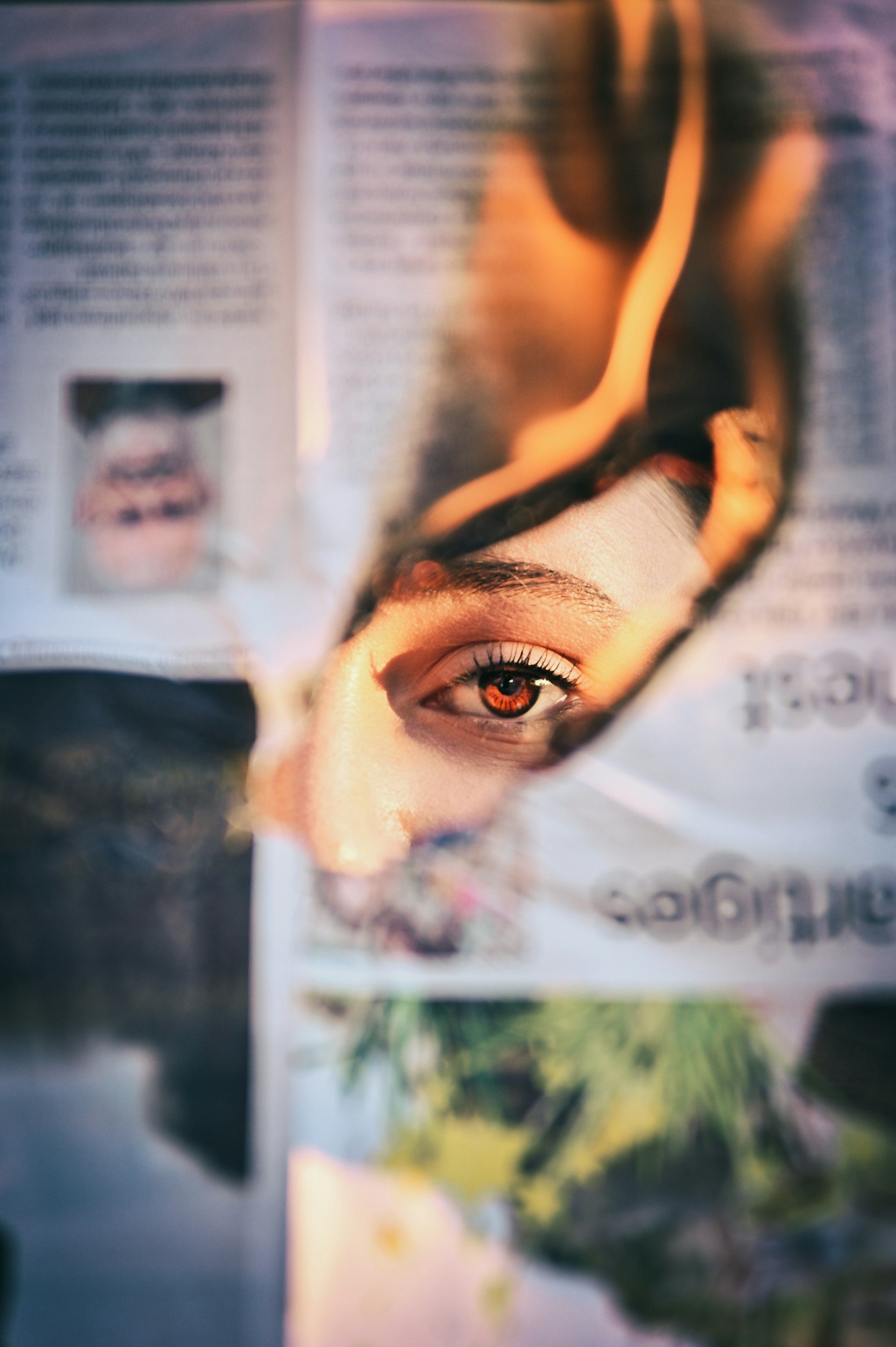

His son, Chuck, later showed us photographic evidence of the battered and faded warning sign we had missed, the one nailed to a tree on the bank, advising strangers to portage their craft around the falls that loomed just up ahead.

Lazily watching Dave in the red saucer forty feet ahead of me, I was suddenly aware that he was somersaulting up and into the water. Oh, I thought, that’s about to happen to me, too.

Before I could wonder what it would feel like, I was catapulted into the frothy white water, tumbling over and over like a load of sodden sheets in a heavy-duty washing machine. My limbs banged silently against underwater rocks, and I held my breath. When the ride was over, I was grateful for the return of sight and sound, but relief was short-lived. I was being swept downstream and I needed to get to the big flat rock on the bank where Dave was lying prone like a dead alewife.

The next few moments were consumed by a monstrous attempt to swim against the current, flailing harder and faster to attain the bank while the rushing river pulled me away from it. But then I was gripping the edge of the rock table, and Dave was standing up, blinking stupidly without his glasses.

He extended one pale, trembling arm to pull me up and we assessed the damage. No broken bones. No apparent concussions. No wristwatches or eyeglasses, either. But Dave’s iPhone, bundled protectively in its OtterBox case, had survived. A few hundred yards from the river, he was able to call for help.

It would be weeks before my bruises healed—months before the scars on my left shin faded—and a couple of years before I understood the significance of that event: I would never again follow a man unthinking. I would have to plan my own adventures and watch for the warning signs myself.

-Judy Peres

Judy Peres is a veteran journalist whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Jerusalem (Israel) Post, The Plentitudes, and numerous other publications. After retiring from her last real job, she joined her partner in Superior, Wis., in an ambitious project to take down the world's biggest grain elevator and reclaim its old-growth wood - a venture that ultimately went up in smoke, She is currently living in Chicago and working on a memoir, Woodchuck.