How I Found Out I Was Raped

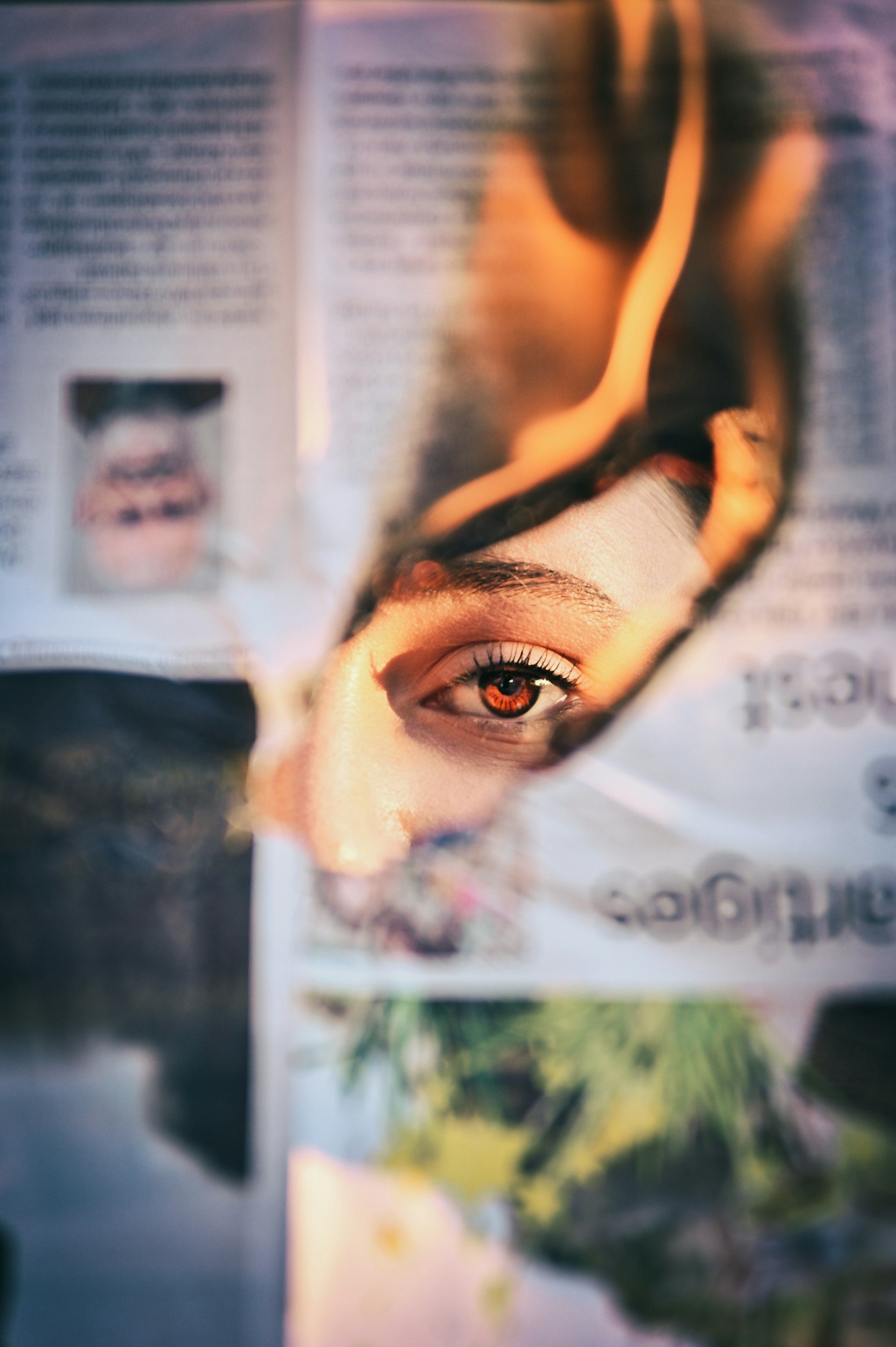

I read an article in our local newspaper about a high school coach who had just been fired for abusing his male students. I was in my early forties, and remember taking in the article (yes, back in the day when people still read an actual newspaper) and contemplating the unpleasant information that a football coach in a city just north of where I lived had inappropriately touched his male students. My next thought was, Oh, that happened to me.

When you are sixteen and raped by a high school teacher, the only way to survive is by disassociation. I recall a few prefatory details, like the first act of play. I went back with Mr. Spillane to his office located at the right side of the stage. I think he held my hand and directed me there. It was a room stuffed full of props, manikins, costumes, beer bottles and all manner of theater trappings piled almost to the ceiling. Masks, scarves, and curtains lay across his desk. Almost all visible flooring was covered in stuff. There was a tattered beige loveseat. We sat down, and he began touching my breasts.

After the prelude—a ‘fragmentary memory’—I now know, I found myself in the bathroom washing my face. In what remains of puzzle pieces, we are sitting together as he rubs my breasts. If I dig deeper, I feel sexual and all powerful. Who else gets solicited by her teacher and privately taken apart from the crowd? After that there is amnesia, until I find a teenager—myself—in the girls’ bathroom, which couldn’t be more different from high school restrooms of the 2020s. I am scrubbing my face with Borax powder dispensed in the 1970s from a non-automatic machine.

I rub this abrasive substance into my face until it reddens, then wash the stuff off. This becomes a new ritual for the rest of school year between each ‘period,’ as they are called. And yet, it is not the answer to “Why are you always late to class?” asked by my mother. She queries me on the subject, not in a punitive way, but rather curiously, in her PhD analytic manner.

Quite fittingly, my rapist was the drama teacher at Parkdale High School in Prince Georges County, Maryland. He was a drunk who smelled of liquor. He drank cheap beer during school, as if to impress upon we students that if he could get away with it, we could, too. Tall and skinny, his face scarred by acne, he was well-liked by seasoned thespians and newbies.

His message: drama class would be different than other classes. It would be fun. He was cool. He was one of us.

We did exercises on the main stage:

“Pretend you are a piece of bacon sizzling in a pan.”

“Pretend you are smoking.”

“Pretend you are waiting at a bus stop (a la Waiting for Godot.) This skit would involve two students in conversation, and a persona who never arrived.

There was an after-school drama club run by Mr. Spillane. The popular kids were all members. I was a member. But after I was raped, I became extremely depressed and dropped out, not only from drama, but my other activities as well. I appear in no pictures in the high school yearbook, because, in fact I missed over forty days of school and avoided being seen, as much as possible.

A close friend said, “You used to be so funny. Now you are always down.”

I couldn’t reply. Time had changed. Every minute seemed like an hour. The body remembers what the mind represses. I also couldn’t sleep, though this was not a new problem. It had worsened. I suffered with insomnia from age eleven—a genetic predisposition. But this new depression was severe and affected family, school, and interpersonal life. Of course, my mother didn’t know what to do when I came to her at night and told her I was upset. She would give me a bear hug and tell me she had confidence in me. I don’t fault her for not knowing how to handle this situation, since in fact, due to the repression of what had happened, I had no language with which to describe what had happened, let alone voice the shame and trauma.

It turns out that Mr. Spillane preyed on other students as well. I learned this in my late forties. I talked to a friend who informed me our classmate S had been molested by Mr. Spillane, and that he’d tried it on a number of other vulnerable teens. Some succumbed, others did not.

One thing I’ve learned with the passing time, and especially after turning seventy—the age when women become invisible—is that my feelings of not wanting to return to Greenbelt, Maryland, where I lived from the age of five to twenty-eight years, are not unusual. PTSD is an inevitable consequence of rape. Another attendant symptom is labeled ‘fear avoidant behavior.’ Despite my fear, which took the form of flying phobia, I went back to Greenbelt, Maryland many times after moving to the Northwest in 1982. I traveled to see family, attend my five-year college reunion, and be there for weddings and funerals.

Yet I always landed with the same shame in the environs of Washington DC. I carry a mixture of unpleasant feelings. It is still my conviction that nothing good ever happened in my home town, although it was there that I got married, birthed our first two beautiful children—a boy and a girl—and received a Master’s degree in English Literature. My husband and I also bought our first home, a townhouse. I had friends whom I never made any effort to see because part of me was running rogue, out of touch with an event that deeply affected my personality. For the majority of my life, I remained unaware of the cause of my morbidity around place.

*

There is no chronology for the victim of a rape. The subconscious stores its memory; the body and the unconscious braid a Celtic knot. One repercussion of stored trauma is having triggers. One case in particular causes me deep regret. When my children were young, our family got a dog, against my wishes. My son bonded with this mixed black lab and named him Nike. I remember walking the dog, cleaning up after it, and generally navigating becoming a dog owner despite not wanting to have the animal. I am a bona fide ‘cat person.’

Nonetheless, the mom part of me adjusted. Until, one summer Saturday in the garage, Nike sniffed my crotch. He did this innocently, as dogs are wont to do. I turned into Medusa, a force to be reckoned with. My gut told me the dog had to go. I didn’t know why but used some reasoning to the effect that the dog was ‘too big for me to walk.’ This was partly true, but it wasn’t by any means the whole story.

Our son was nine-years-old at the time. The news broke his heart. By the end of that day, we had re-homed Nike in a farm to the south, a place where ‘he would have room to run.’ This sudden decision hurt my son. I don’t believe he ever recovered, and I never talked about what happened, because, quite honestly, at the time, I didn’t know.

*

I had sex with my boyfriend at the age of sixteen, and I was not a virgin. There was no blood after intercourse. The strangeness of that fact never made sense, yet it was not a subject to bring up, think about, or wonder about. Too many other changes go on in a teenager’s life. My parents were permissive; they had no boundaries or curfews. There was no discussion about sexuality, nor was there any emotional attunement in my family of origin.

Understandably so, for my parents came to Canada by way of European persecution, and my father came to Maryland for a job at NASA. Only now does this factoid fit into the one thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle that rape becomes across a lifetime. Another fact: I was promiscuous. This goes with the territory.

*

Episodic remnants of this event remain a core wound. But I am no longer into excavation. I have had other physical traumas, and realize that by virtue of its wisdom, the body knows best what to remember and what not to. It’s a blessing to have had the opportunity to share my experience with my own two grown daughters and now seventeen-year-old grand-daughters—sororal twins. A year ago, when the ‘grands’ were the same age as me at the time of the life-changing event, I decided to tell them. They listened to my disclosure quietly and with some signs of surprise. They gave me compassion, understanding, and emotional support.

In addition, I have been reassured by my older daughter that her girls—now young women—receive, in public school, information on what is appropriate behavior from power figures and what is not. The concept of ‘consent’ is discussed in Health and other classes. This eased my mind, especially because sexuality has become a shark in bloody waters, thanks to a dominant patriarchal culture and social media.

*

It is the 21st century. One in six American women in the US are victims of rape. There are no repercussions for perpetrators. How many young women hold amnesia as a saving grace? Do those who survive have the chance to be heard by extended family? Are we to continue this displacement by male-instigated war and acts of violence? Must we wander the earth in states of limbo, guilt, and shame?

-Judith Skillman

Judith Skillman’s poems have appeared in Commonweal, Threepenny Review, Zyzzyva, and other literary journals. She has received awards from Academy of American Poets and Artist Trust. Oscar the Misanthropist won the 2021 Floating Bridge Press Chapbook Award. Her recent collection is Subterranean Address, New & Selected Poems, Deerbrook Editions 2023. Visit www.judithskillman.com