Panda and Tiger

Maybe the woman holding the child was way too close to the edge of the pier. Way too close for way too long. Maybe that is what the shopkeeper told the Vancouver police when she phoned in her response to the Amber Alert. Maybe the ginger-haired artist who owned the Rare Button Shoppe—herself the mother of a curly-headed toddler—feared for the safety of the child on the pier.

Maybe the shop owner felt a fondness for the child, having given the doe-eyed angel a cherry-ball sucker when the older woman and child visited the button shop. Maybe, during that visit, the shop owner asked the older woman, who she assumed was the child’s grandmother, if she could hold the child. And maybe the grandmother said, “Yes.”

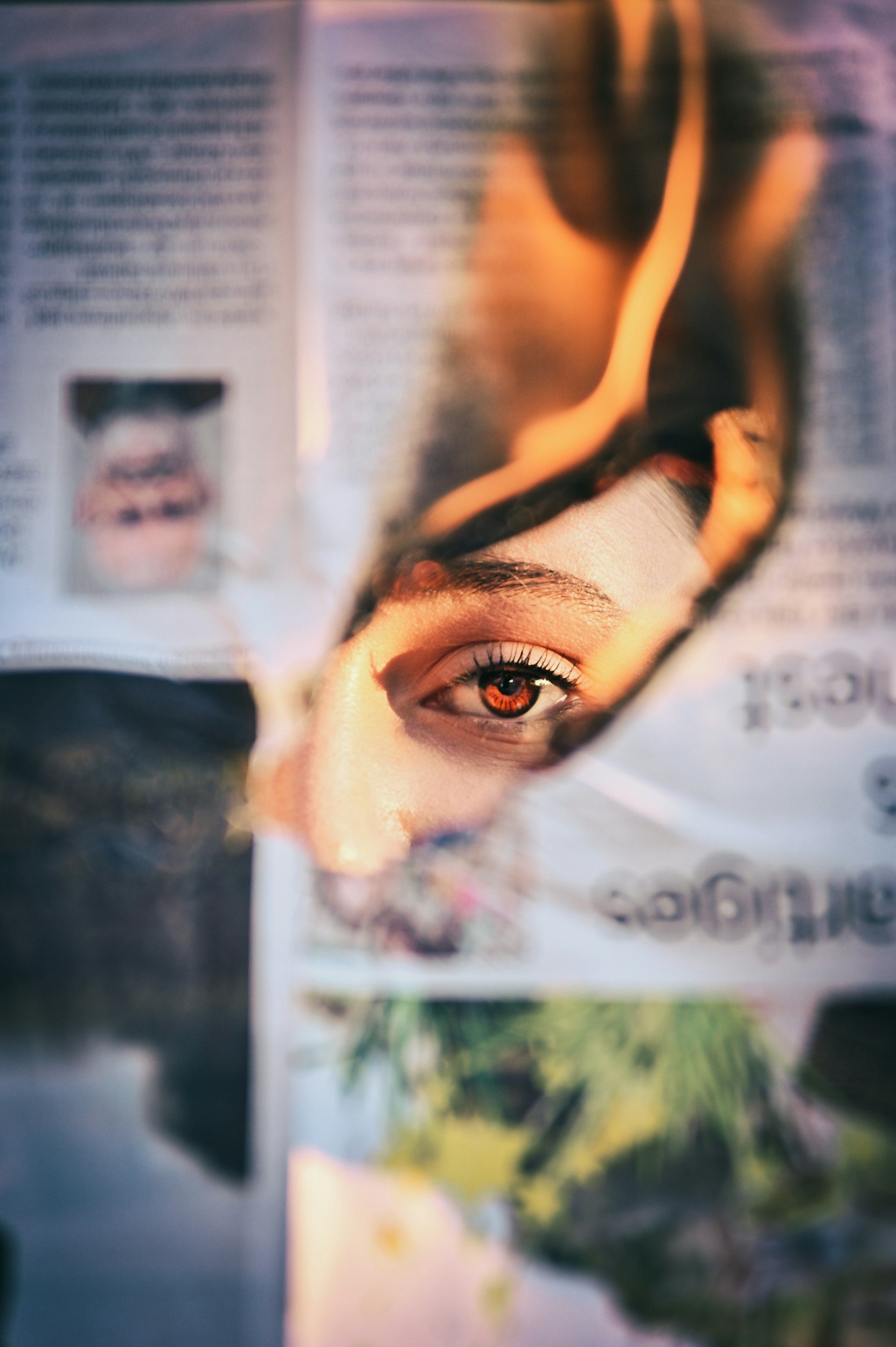

Maybe the elegant button-maker carried the child to her prize button collection: zoo animals formed from porcelain. Maybe the wide-eyed toddler pointed and whispered, “Panda, tiger.” And that is when the shopkeeper gave the tiny boy those buttons—the porcelain panda and the tiger.

Maybe this graceful button maker wore a woven lavender smock latched with the very same soap-stone buttons the grandmother bought at the button store.

Maybe later the grandmother spotted the shopkeeper watching her from the button shop window. Maybe that’s why the grandmother put the child back into the stroller and walked away from the edge of the pier.

It is possible that the grandmother forgot the name of the café where she and the child were to meet Rose. It is possible she got lost, was confused, or maybe even dozed off. And, yes, it is possible that she never intended to meet Rose for lunch. It is possible that the grandmother had another plan.

Waiting in the café, Rose pressed her forehead to the cool window, breathing clouds of fog onto the glass. The hostess who delivered the steaming café au lait, with a foam heart floating on the surface, reassured Rose that she was on the alert for her lunch party—a grandmother with a toddler.

Rose inhaled the delicious mixture of coffee, nutmeg, and cinnamon and, with her finger, traced the floating heart until it broke into dots of cream and one tiny swirling tornado. It was at that moment, watching the cream spin—less than twenty minutes into the wait—that Rose tasted a familiar sourness in her mouth and felt her stomach twist.

And yes, for sure, at twenty-six minutes into the wait, Rose wondered, Did I invite this game? Did I set in motion that old Charlie Brown, Lucy scrimmage? The one where Charlie wants to play, but Lucy wants to hurt somebody?

It was at twenty-eight minutes into the restaurant wait, heart beating furiously, that Rose recalled her mother’s Saturday morning rampages. The ones where Rose made peanut butter sandwiches and stashed her siblings safely into the car parked in the driveway—inventing and orchestrating fantasy trips to the beach.

And at thirty-two minutes into the wait, body vibrating, Rose recalled the policeman’s stern lecture—delivered decades ago—warning her mother that it was against the law to leave tiny children alone at home even if the parent was attending morning mass.

This memory was interrupted by the hostess, who, alarmed by Rose’s obvious distress and well-schooled in the Emergency Protocol of Grandville Island, called the Vancouver police.

Rose was astonished at how quickly the shopkeepers on Grandville Island cooperated with the Amber Alert. Grateful that the petite raven-haired police woman with the walkie-talkie shared every hopeful report with Rose as the two women sat on a rain-soaked bench beside False Creek.

Yes, the manager of the yarn shop did spot an older woman with a toddler, as did salespeople at the art supply warehouse, the printer at the print shop, the actors working the puppet show, and that artist who owned the Rare Button Shoppe.

Rose peppered these reported sightings with her own private, frenzied speculations: an imagined heart attack, a massive stroke, perhaps early Alzheimer’s. Then chilling visions of an old woman floating face down in False Creek or lying on a stone path, her head split open. In each of these nightmare visions, the toddler was buckled into his stroller, screaming. Or worse.

The diminutive officer sat on the bench next to Rose and explained her role as Director of the Domestic Violence Unit. After a long wait, sometime around 1:30 in the morning, the officer’s walkie-talkie squawked back to life. The movie theatre manager, closing for the night, had discovered an older woman and a sleeping child.

For Rose, there was more waiting on the bench as the EMTs and the D.V. officer conducted their examinations. Then, the officer carried the sleeping child past vehicles wild with flashing lights and placed him gently in his mother’s arms. Rose pressed her son to her heart, rocking the little one. Her body buzzing with relief.

Then came the phone call to the judge. Awakened so early in the morning, he growled “shit” many times until, settled in his bathrobe and well coffee-ed, he felt composed enough to rule on the law. His ruling? Solidly inspired by King Solomon. “This court, my court, is Canadian. The child is American. I will let the child’s mother decide.”

“Decide what?” Rose asked, rocking from foot to foot, snuggling the exhausted toddler. She looked over her shoulder at her mother, pouting and mute in the back seat of a police vehicle.

The judge snapped back, “Decide if the old woman goes to jail charged with kidnapping; a ruling that would be mandatory for a Canadian citizen. Or send her back to the States where this problem belongs.”

Rose’s heart pounded, as sore as if stabbed. Her mind flooded with images of the Vancouver vacation: museums, boat rides, the Zoo, and the feast at the Spaghetti Factory. Mounds of noodles capped with parmesan cheese—steamy air perfumed with garlic and tomato sauce. Wine goblets toasting a giggling baby’s sippy cup. Yes, her mother had smiled. Her mother had laughed.

Rose strained to remember. Perhaps her mother had bristled when asked to babysit that morning. Babysit while Rose gave a keynote address. It was only a two hour speech, but her mother had bristled. Perhaps that was the reason for all the mess. Or was it that the rest of the vacation had gone so well?

For hours Rose had been hijacked by fearful and confusing possibilities. But in this moment, Rose was certain of three things.

Rose did not have the funds, the time, nor the desire to stay in Vancouver and prosecute the case. And, to be honest, Rose did not have the guts. The guts to lock her mother in prison or commit her to a psych ward for what the judge speculated could be a term of three years.

Rose had a life. And, in that life, she had a beautiful boy to raise and classes to teach on Monday morning. Game over. The woman would have to punish or fix herself.

The petite D.V. Officer took hold of Rose’s arm. Then eye to eye, she delivered an order, “Stop trying to please her. It’s time to let go.”

Rose took in a deep breath—a breath filled with the sweetness of a Spring morning.

“I will let her go,” Rose vowed, feeling her heart relax into freedom.

Rose pressed her sleeping son close to her heart. She kissed her baby’s head. He stirred in her arms, his little hand still squeezing a panda and a tiger.

-Mary Frances Schneider

Mary-Frances is a writer, screenwriter, and storyteller. She is the author of two young adult novels: Dear Cookie and Molly McCumber, I've Got Your Number; as well as two award-winning screenplays, Saving Grace and The Summer She Turned Zero. For the past two years, Mary-Frances produced Telling Stories @ the Oil Lamp Theater. She lives in Chicago with her husband Pete.