The Hard Answer

Once a year at the place I work we have this training. It starts off like most trainings you’d have at your work. Everyone comes together, complaining that they have better things to do than be here at this. You find your friends and sit together and talk about your day so far. We have an expert come in and talk to us, and then we do some group work on the topic and call it a day. It’s a workplace training that myself and the people I work with are used to. It’s a training for what to do if there an active shooter in my building. My building is an elementary school that is filled with 800 children everyday. The active shooter training is the one we dread the most. We are educators, not police or military. We are experts in reading, and math, not barricading and disarming. Yet, there we are. Learning how to do those very things from some very brave police officers.

The worst part about the training is when we actually pretend there is an active shooter there. The person fires blanks and tries to get into our classrooms—tricks us into thinking its safe to come out, and will occasionally take a hostage. It’s pretend. We know it’s pretend. But the sounds are real, the smells are real, and our actions have to be very real. We have children to protect. Precious children who have been entrusted to us by their parents. Every single adult I work with would put themselves in the line of fire to protect those children. It’s not even a question.

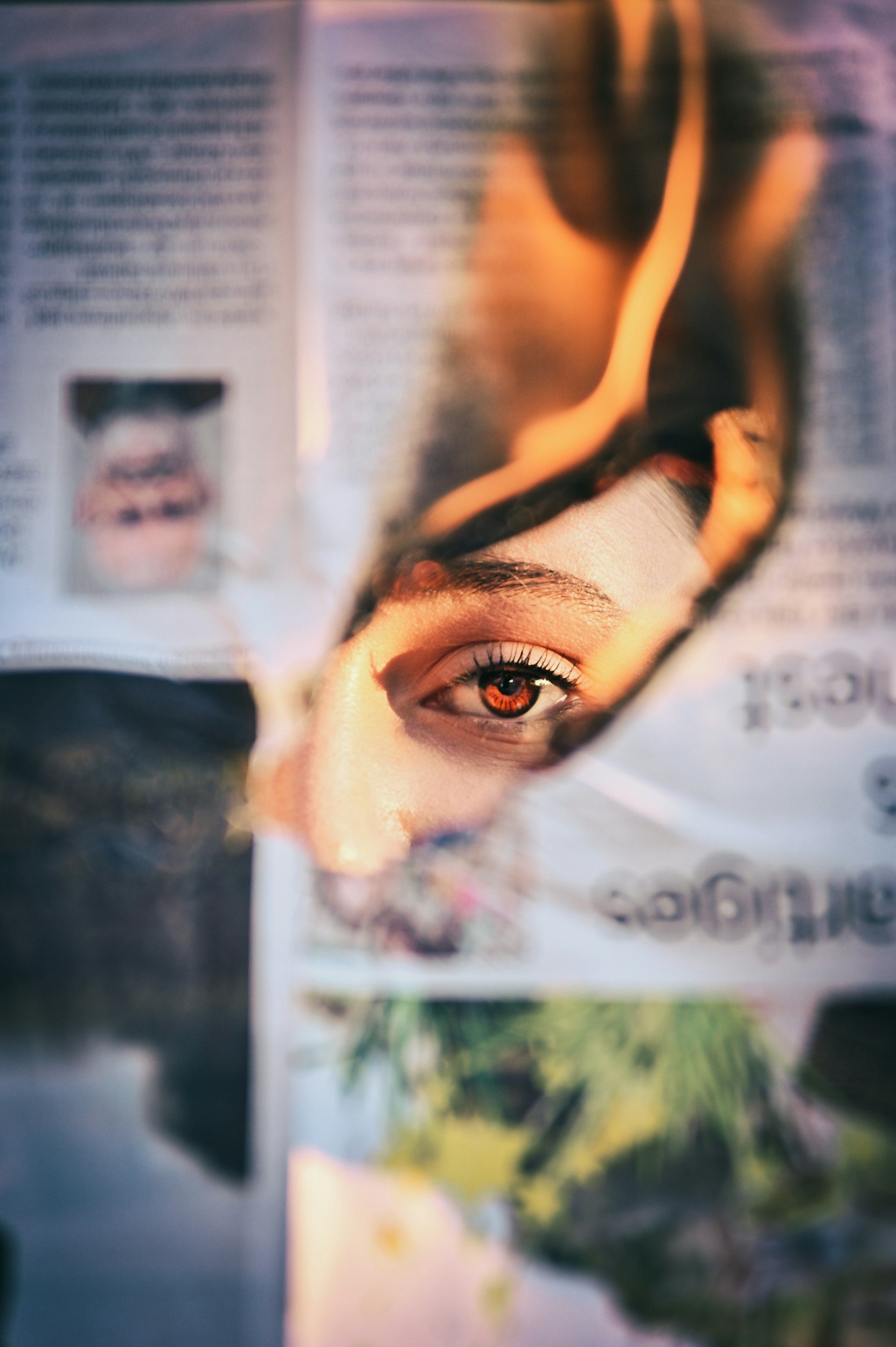

So, like clock work, once a year we practice. As we huddle in classrooms, knowing truly we are safe, the thoughts still run through our head—the what ifs, and wheres, and whens. The thoughts of Newtown and Columbine. Thoughts we dare not speak in that training, because as pretend as the training is, we get a fractional glimpse of what it was like there. And it terrifies us. We think of the faces of our beloved students and tell ourselves, “whatever it takes, I’d do it, I’d keep them safe whatever it takes.”

But should we have to think that?

Should we teachers, aides, counselors, and principals have to think that?

I work at an elementary school, not a military base.

Should we have to have a training where we learn how to take down an armed intruder who has come into our world of songs, and books, and art, and love?

Should we have to panic every time we go on lock down because we don’t really know what’s going on, or if this is it?

I don’t know the answer. I’m an educator, not a policy maker. It’s a hard question and an even harder answer. I’m not sure if we’re ready to hear it as a nation, but I look at my co-workers during the training, they try to act like it’s normal, as we push tiny desks up against the door and plan how we’d instruct first graders to throw books at whoever comes through that door. Practice yelling the location of the shooter. Rehearse asking the officer to show me his badge because he might be tricking me. We practice running out of the building to safety. But I see it. I see the fear and the questions in my coworkers. I feel it myself. There are so many questions. But I know we need an answer.

-Kelly Albrecht