Once and for Always - A Brief

Almost metaphysically

It’s going on thirty-six years, yet I still argue with the thing. While walking in the neighborhood, I sketch out plans for a new beginning that will free me from the past. Or, say, I think that I will not think about it, but end up not fully admitting to consciousness the trauma surrounding what seems to have snowballed into its own life-form. A mass of pain, located in my lumbar spine—I know the discs leak fluid, though the last MRI showed bulges but no actual herniation. Yet I can tell, and when I visited the back doctor two weeks ago, he set me up for a different kind of steroid injection: “epidural L5/S1”. After that, my autonomic system freaked and produced that lupus-like rash, accompanied by a return of insomnia.

*

Let’s stabilize your spine

And now, a year after the two-level lumbar fusion (L4/5 –S1) the pain is on a campaign of its own to co-opt any semblance of normal life. I wrestle it into the shower, take it on walks, stay home while my husband goes on camping trips. I cry and read endless self-help books—there is an infinite array—on chronic pain. I learn that the alarm system is faulty. Hardwired. Wrong. Neuroplasticity? I no longer believe in that.

There are poems and stories to be made of this event and some have come to fruition. OK, perhaps not stories. A memo, a brief? The only story I hold is one carried inside and taken away by the insistence of mortality. Too bad, the violin, an instrument I once loved, lays un-played. My back aches even at the skeletal stand—I used to forget a little in a scale.

*

As a child learns to walk

Why not go on with the bits I can remember clearly? Allow me the liberty to go back and forth. Perhaps much of what lives on in one’s memory is inexplicable—the 99% factor, let’s call it. The life of a singular human being can not be known. But if the one percent might prove useful even to one person? Do I then hold an obligation to continue trying to explain? I expect the answer will be affirmative. I believe enough in God, whomever or whatever presence that made itself known to me when I was standing as a child beneath a fir in winter—palpably a being that was not myself, visited, and then left with the same ease as that with which I lifted the boughs to enter the secret place known only to children.

*

Premise disproven

I suspect that re-making this traumatic event will free me. But I live in my body and know that assumption to be false.

The accident that changed my life occurred on November 11th, 1982. I like to think I forgave the driver of the Buick who hit me and my two-year-old son as I was carrying him across a street in Factoria. This happened in Bellevue Washington, three months after we’d moved there from the east coast. “Factoria” has been aptly named “Fucktoria,” by the lovely Thea, my forty-two-year-old daughter’s sister in law. I can go to Fucktoria to shop for groceries, get a car wash, or eat in the Thai restaurant whose bamboo framed windows gaze out on the street where I lay unconscious, and then, culminating to screaming for my son Andrew, whom I thought was killed.

*

Forgive and forget is bull***t

To delve into the “accident” is not only troubling; it goes against the mantra I’ve been trying to employ in this, my sixth decade: “Don’t Rehearse the Past.” What good can come from rehashing scenes? The accident with its accompanying sirens never recedes. It cries out for attention. Even after I forgave the driver, that “accident” where I was hit by a car in the fifth lane of a five-lane road refuses to be put to bed, so to speak. Perhaps writing it down provides some kind of resolution? They say writing it down can be therapeutic.

I never met the driver of the Buick, nor the middle-aged wife I picture riding along beside him with her hair colored and curled, an almost blonde redhead—I wonder where that image comes from. Other pictures: shopping for a raincoat for my husband, carrying my two-year-old son on my hip. Getting Drew – as we call him now, in the no longer existing past, or the past that I remember yet cannot touch, he was Andrew— a toy, a Lego motorcycle with a policeman on it. Then the Junker car not starting and walking across the parking lot to what was a Dunkin’ Donuts, where policemen were hanging out, telling the cashier my car had broken down, asking where the nearest gas station was. No one offered to help me. Why not?

Assigning blame is one of the things I’ve done for these thirty-seven of the thirty-eight years since the event. I learned that doesn’t help. After asking, I stood at the corner, waiting for a break in traffic, and crossed the street. That is all I remember. The rest is pieced together like a quilt, from memories, dreams, and what other people said. But the body remembers everything, and it will die with those memories, or rather, those memories will die with it.

*

Dear Diary

I’ve decided to diary, if that can be used as a verb, rather than trying to tell the story. This is a story that will only end with death—mine—I’m fairly sure the driver of the Buick is dead by now. He was—from some image I have though I never saw him, never met him, nor did he come to the hospital—middle-aged. His insurance company was all over me like sharks the day after. Maybe it was three days after. Maybe they waited until the concussion passed and I knew my boy was alive. In any case, they said it was my fault. More on that later.

Meanwhile, it is time to visit the back doctor and request another steroid injection. The lower back pain has become unlivable once again. The right hip pain as well. I have sacroiliitis and five bulging discs, from L/2 – L/5, but the way they number them is strange so it’s five. OK, maybe four. What’s the difference? It hurts but it’s better than being paralyzed.

1 February 2016

wrote nothing

1 March 2016

wrote nothing

*

In the beginning

I loved gymnastics. The uneven bars were my ‘specialty’. I could kip like nobody’s business, and I did it over and over, practicing until my palms blistered and bled. From a kip on the low bar, one can pull the legs through hands and, using momentum, grab the upper bar with arms spread. It’s a bird-like sport—all the swinging, as if from branches, and the supple bar bent like a branch with my weight. That was, technically, under the weight I should have been for a five-foot-two-inch fifteen-year-old.

That may have been why my periods were irregular until the age of twenty. Or, who knows, it could have been just another vestige—a forerunner, perhaps – of the ovarian cystic disease I grew to have in my late thirties and early forties. A fascination with the body’s traumas would be nothing new to someone who came from the Ashkenazi background I had no choice in choosing.

*

Let’s leave it off here; I can tell I need to move around or else I will become frozen like that dead tree in the corner of the yard, the one of no color except a slight tinge of lichen, with its lack of sap and the silly twigs poking out as if to distract from the fact that it’s as dead as a dog on the sidewalk. That’s what Bill said death was: when you die, you’re as dead as a dog on the sidewalk.

Bill did not believe in God. He was from West Virginia and an architect. He remarried but I doubt that changed his lack of faith.

Let’s just leave it there. Even after the lumbar fusion, I can’t sit in a chair for more than twenty minutes. Have you heard of DOMS? Oh good. I’m glad you haven’t. It’s the cruel aftermath of doing anything. Delayed Onset Muscle Syndrome. Because there is a price for everything, and that price must be paid in full.

Because,

accidents happen.

- Judith Skillman

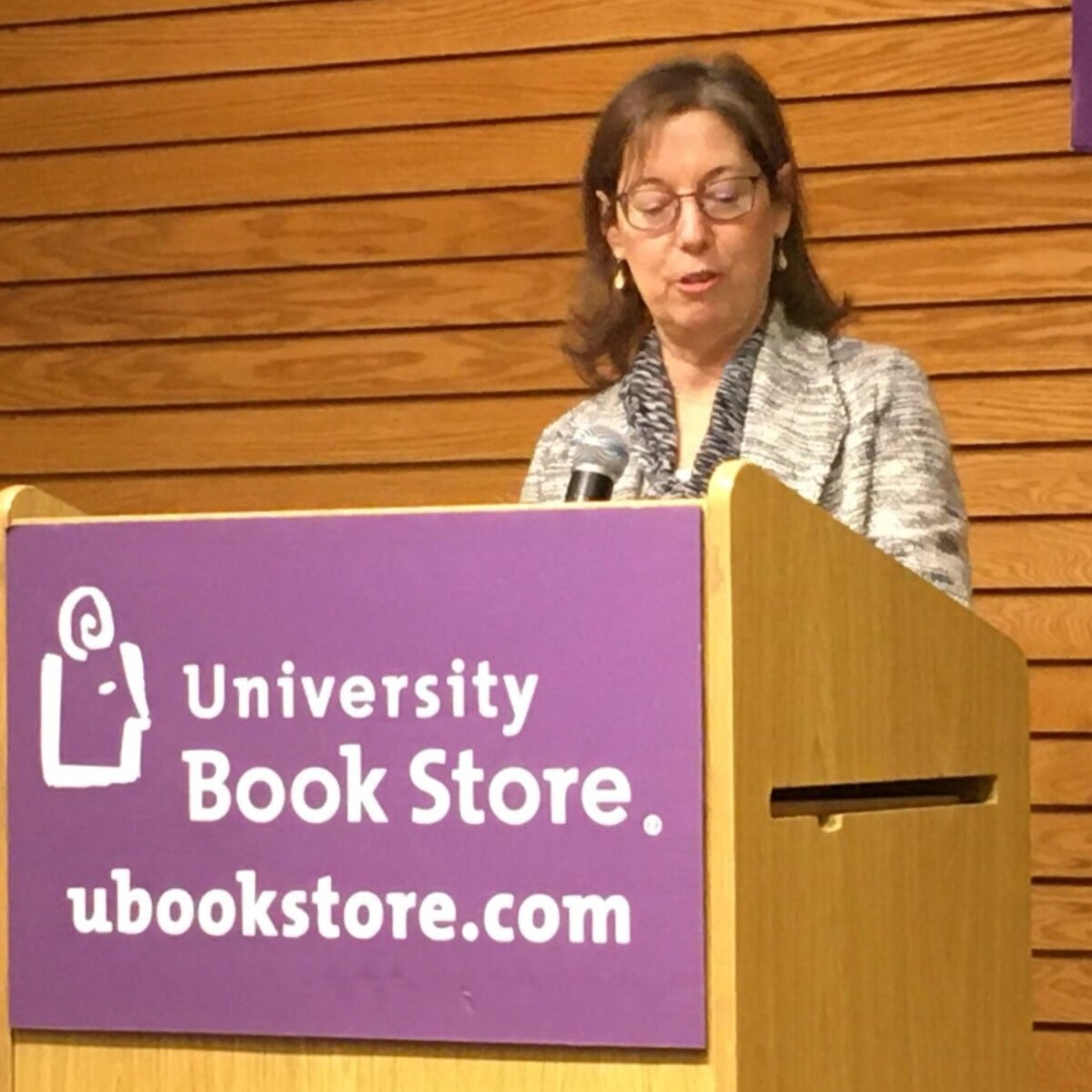

Judith Skillman is the recipient of awards from Academy of American Poets and Artist Trust. She is the author of The Truth About Our American Births. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Shenandoah, The Southern Review, and Zyzzyva. Skillman is a faculty member at the Richard Hugo House in Seattle, Washington. Visit www.judithskillman.com