On Aphasia

“There are two parts of the mind. The outer mind that records facts and the inner mind that says ‘Yes’ and ‘no.” –Agnes Martin

1.

Once, years back, a woman, an acquaintance, asked me why I decided to become a speech-language pathologist, a person who works on helping children who can’t say their rs, who sits in quiet classrooms with the thud of the other, happier children outside, or who leans in, in the dead of winter, in a trailer because that’s the only extra space, a metallic trailer with stucco on the sides, and who rehearses the way sounds go. She was asking why I wanted to work on helping children whose rs sounded like ws, who said wabbit instead of rabbit, and who frowned when I asked them to open their mouths and check, using a mirror, the placement of their tongues when they spoke. She was asking why I would want to work with children who laughed when kicking balls in the recess yard, playing four-square or soccer, but who sat, as if words were foreign things, when they met me; who seemed reticent, and somber, even unwell.

She was asking, I suspected, because she imagined me holding a mirror to the mouth of this one, or a tongue depressor to the tongue of another, or simply blowing imaginary bubbles to show how those sounds were formed. Or maybe she was asking because she too had had her troubles with speaking and had come out on the other end, mostly unscathed, a professional woman who only had that small secret to hide. Maybe she, like so many adults I’d met over the years, told no one in her everyday life about her elementary school years, those long years of days where she’d gone to a separate classroom. But that memory was hiding inside her, waiting for someone to incite it, to bring it up, or hint at it—and then, it would come bubbling out.

As we sat together, heading on a bus to visit mutual friends, she glanced out the window, thinking most likely of the still and clinical quiet of the rooms I must work in; rooms with no bright yellow bulletin boards or children’s swooping drawings of clouds; rooms where children were meant to avoid distraction; rooms with an antiseptic smell. Her look, when she turned to me, was pitying, thinking less of hope than of anxiety and embarrassment, the awful awkwardness of children bursting with ideas, who sensed their words came out distorted, their phrases stuttered, their thoughts and passions constantly tamped down.

“It is a strange thing,” she said, with a downcast glance at me, as the bus trundled down the traffic-packed street, “to want to work with kids who can’t talk well.”

“Why strange?” I asked.

“Something must have led you to it.” She was a psychotherapist. “Don’t you think?”

“I don’t know.” But we both knew it was true. “Why do you ask?”

“Oh, so now you’re turning the question around?” A small laugh, not complicit.

“I like working with kids.” It was a simple answer, but true. “I like the mystery of it.”

“But more than that.” The bus heaved to a stop.

“Let me think.”

2.

In the end, I told her that it had nothing to do with the children I had met, or would, though I learned to find them fascinating. It had nothing to do with the adults either, those people I’d come to meet who struggled after rock-climbing accidents or scuba diving accidents or strokes to say more than a single word. It was instead a fascination with sound, and language, and memory. It was a question of mine, from many years back, about how language forms out of sound. How do we make sense of the jumble of sounds that come out of our mouths and the mouths of others? How do we use sound to capture memory? And how can we manage when language feels so imperfect? When time seems forever shaped by language, but out of our grasp?

How can we manage when so much remains visceral, things that only the body knows? When I hear of the death of a relative and I curl up, curl into a fetal position, knowing that any facility with language will get me nowhere?

The body knows, ultimately, so much more than the mind.

The body knows itself from a time before language.

That’s what first startled me, and continues to startle me now.

3.

That sub-verbal language, or pre-verbal language, the language of the body, has more to do with witnessing than anything else. It has to do with the rumble of the car engine down the driveway of my childhood house as I waited for my father to arrive. It has to do with the scarcity of air I felt when I played piano; that sense that, in the minor and major scales, in the furor of Rachmaninoff or the peace of the Goldberg Variations, I was pressing myself more deeply into myself, into a place where bones and organs, capillaries and veins, were nothing more than coursing, pressing instances of a common humanity. So often I have tried to capture those moments in words, to articulate that strange mixture of doubt and desire that found and continues to find me, whenever I even hear that music played, and yet every day, repetitively, I fail.

I fail because I too have only the words of this language. No matter how numerous those words, no matter how many other languages I try to learn, the fumbled syllables of Spanish or the more fluent ones of French, I never arrive at that pre-verbal, or sub-verbal, state.

It’s not that I don’t try. It’s not that I don’t long for purely visual ways of making meaning. For years, I’ve dabbled in printmaking and drawing, trying to make them do what my words could not. I’ve tried to still my mind and allow the meditative swoops over the page to do that kind of mental work for me. At times, I get lost in the meditative process. For a while, I love the brush-swoop, the dazzling splay of cadmium blue or burnt orange, or the brush of ink that reveals the underlying gesture. But as I’ve come to find, my ideas are better, or at least more expansive, than my skills. Like a child frustrated by messy fingerpainting—the swirl of brown where he wanted green and gold—I sense my reach is beyond my grasp. Often, petulantly, rather than seeing it as an avenue, I curse the years of practice I’d need to improve.

Could I turn back now, I sometimes wonder—start the clock again and learn to paint, or more generally, dive into the purely visual? And would that, could that, do anything? Would it not simply substitute one limitation for another, one hope for the next?

Every medium has its borders, its tools, its lines that ought not to be crossed. Every speech has the potential for silence, as every living presence has, lying in wait, its ghost.

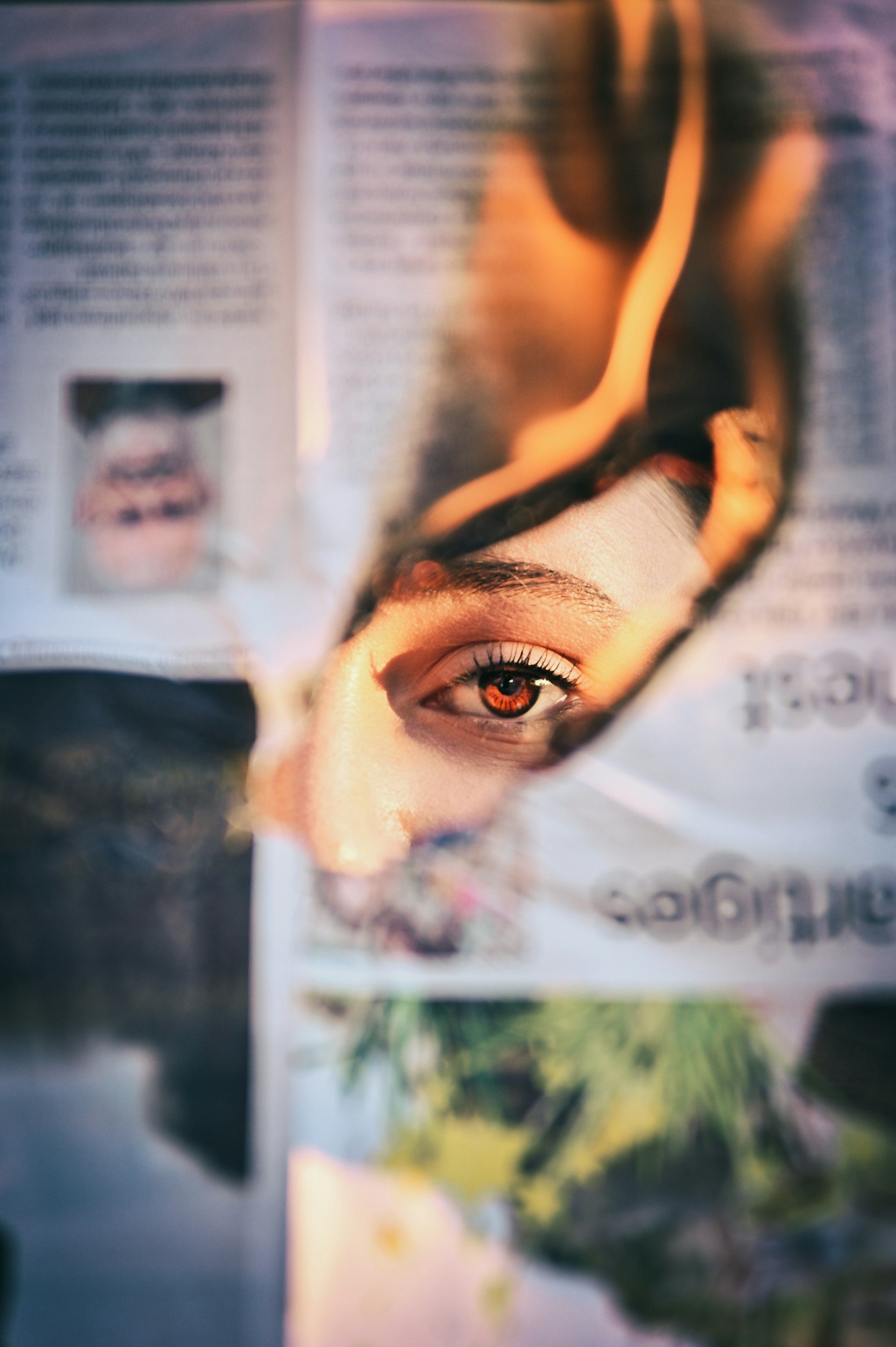

I’m interested, I could have told that woman, in the ways language can ghost us—or the ways we, in striving to grasp it, force it away. I’m interested in ways we try to be heard, whether in language or beyond, in the dip of a paintbrush into water, that subtle S shape on the page, or the touch of a lover afterward. That movement from internal to external, from thought to communication, is a thing I can’t stop thinking of; the same way I can’t stop using words.

4.

I came to this profession, I said, out of a love of language, but since then, I’ve realized it’s not so. I came to it, instead, because of so many late nights listening to the rain, wondering what it was the rain had to teach—its drumming, insistent, on the roof of my Georgia house, the deadbeat thrum of the woodpecker, who’d permanently housed itself in the eaves. I came to this profession because of the ways I used to scribble, over and over, on a blank page, sitting on the back porch of my house, to soothe my mind. There weren’t words on the page, only doodles, black clouds that swerved into thunderstorms—and yet, it was perhaps that wordlessness that soothed me, the sense of making meaning without needing to articulate.

Those scribbles could be interpreted as clouds or the outlines of blouses, or houses, or flooded riverbeds—or as no more than the stirrings of an anxious mind. The possibilities bloomed before me, as a child, and I leaned into them, wanting nothing more than to dive into those swirling depths, to leave my body and enter a sturdier, and purely concrete, world.

I wanted someone to read them, I realize now, to hear what my mind was telling my body, which I could not or would not articulate, messages that would appear later, in all their reddish insistence, as hives. I wanted someone to articulate the longings those scribbles contained, to say bear or fire or brother or nightmare, or if not to articulate them, to sit with me in silence as they unspooled, allowing the urges to be pieced apart, and named.

-Rebecca Rolland

Rebecca Rolland is the author of The Art of Talking with Children (HarperOne, 2022) and lives in Boston.