Illumination

In the minutes after she was born, all of the lights came on. We watched her climb thewall of my body and land, exhausted, at the shore of my breast. Under the sharp white of hospital light, they did the weighing and measuring, and she screamed so that every number and value only reached my ears as alive, alive, more evidence of her realness, her presence. She sent howls up into a brightness that must have been like looking at the sun.

The days of my labor had been drizzly and cold, the air a thin gray, sparkling with a continuous mist. On the drive home, I leaned back to keep one hand on her car seat, marveled out loud at the brilliance of color and explosion of light that had taken place in the hours since her birth. A painted landscape drifted past, the world hanging its best work from the highest beams, rays of light directed expertly toward the finest details.

It will look like an egg, the nurses said, curving thumbs and index fingers in an oval shape. It will look like swelling, like heavy bleeding. It will look like sweating, a racing heart. It will look like falling asleep.

They talked to me of the blood I lost, measured and marked down somewhere. They checked and re-checked to be sure it stopped. They warned me of my own health, urged me to be aware of my limits. I nodded, a promise to take care of us both. I would have said anything, I was on that kind of high you get after a long journey, when you see your house from the end of the dark street and all the lights are on. Everything was waiting for me. I was radiant with the warmth of the little life in my arms. Mortality was impossible. I would be here as long as she was.

I consider it through the sleepless nights in those first weeks, the egg shape of it. I knew they chose the egg as an illustrative device because of its universality, its commonality, all of our ability to conjure an imaginary egg into our palms for size comparison, but I couldn’t stop thinking of the egg’s importance to the metaphor of life, of birth, and wonder why they didn’t choose something else to associate with danger, death. A lime, for instance. A palm-sized stone.

By the time you deliver, they’ve already used all of the fruits to describe the size of the baby. Stones are too varied, too subjective: Your palm or mine? The egg is unmistakable, universal.

*

She carries it to me in the pillow of her palm, but will not risk the transfer into mine. Together we look into the curve of her small hands as she tells me where she found the blue egg, just there, she says, in the grass. With her permission, I pick up the egg, notice its lack of significant weight, the threadline of a tiny crack across its equator, the pinhole. I note the lateness of the season, when mother birds are emptying their nests, sending the duds to the ground to make room for the hatchlings.

“Some eggs don’t have a baby in them, did you know that?” I offer. “They fall on the ground, and they don’t hatch.”

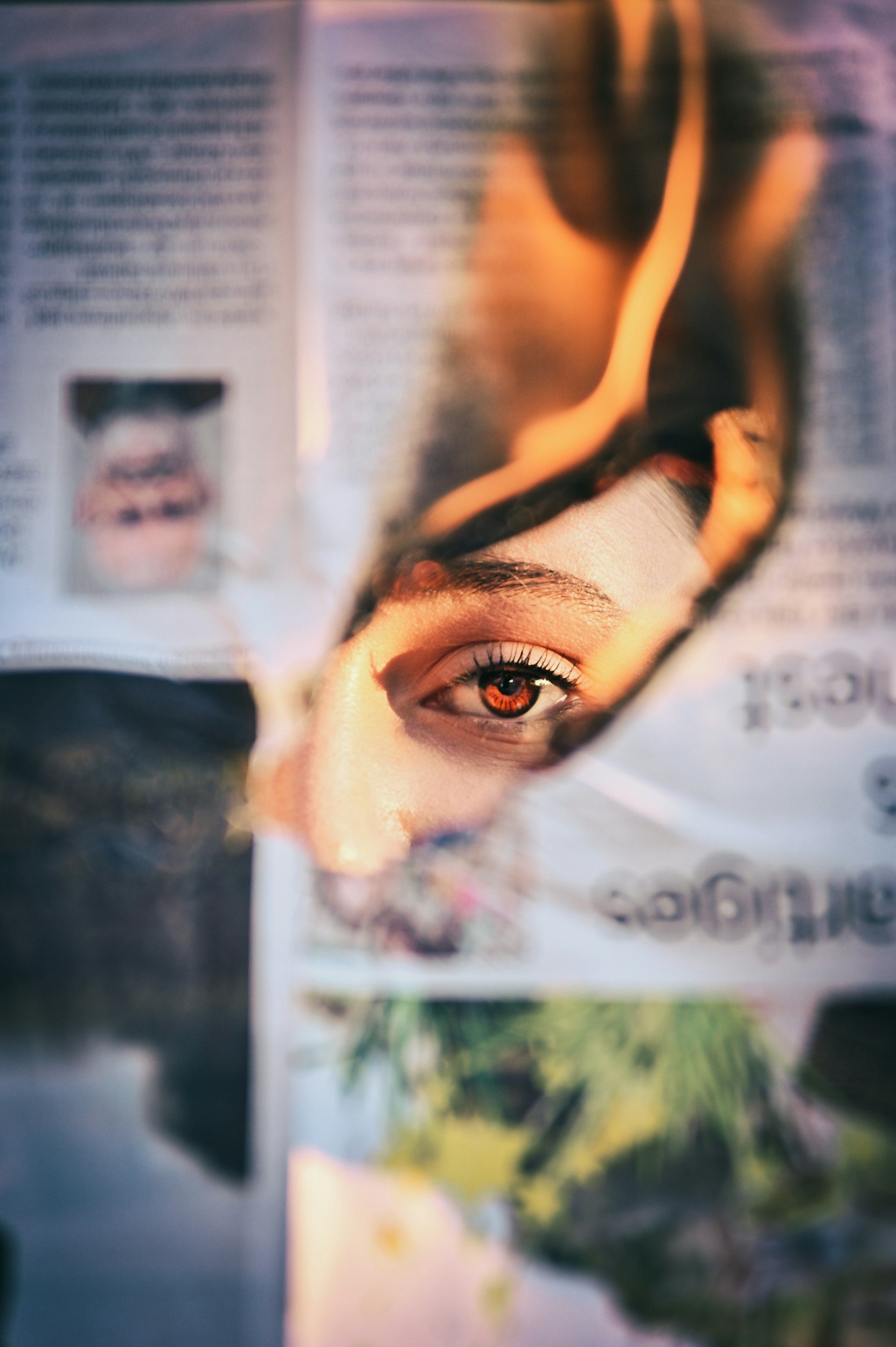

“It’s going to hatch,” she says. She plucks the egg from my hand and leaves my orbit, I’m not playing right. “We’re going to have a baby bird!” she calls over her shoulder. With her back to me, she slows, tilts the egg up to the sunlight, searching.

“We will have to keep it safe,” I say. She is four, and I have become very good at keeping secrets, judicious, even. Together, we make a tiny bed of tissue and tuck the egg into the bottom of a plastic cup. It sits on the basement windowsill until some future day when I decide she has forgotten about it. In the early afternoon sunlight, I imagine the shadow of the tiny crack appearing against the empty white wall inside the shell.

My husband says it happened in the back of the SUV, that this is the way they do it now, instead of in an office or an unfamiliar room where the smell of fear and other animals makes dying more difficult. “I held him back there,” he says, “in a blanket, and they came out and did it.” He hands me the dog’s collar, and we take turns touching it, rubbing our thumbs along its familiar roughness. His eyes shine with tears and are swollen with red threads, his voice shakes. “I can’t tell her,” he says, “I can’t do it. Not yet. I can’t.”

I say I will do it, I say I can do it, but this is before I have done it, so anything I say might be a lie. I say I will do it because I have to do it, I am the only one for the job. What is this but another example of the work of motherhood: being suddenly handed a responsibility for which you’re not certain you’re qualified? Still, I waver. I wait. I ask Google how long I can feasibly put this off, I look for ways around introducing my child to the concept of death, about which I could answer few questions, and none of them honestly.

I say I will do it, but there is a wrongness in it I can’t see my way around, in introducing my child’s first emotional injury, the first pain I can’t fix. It feels antithetical to mothering, nurturing, a wrinkle in the very principle of it. It feels like pushing on some celestial door and seeing it open a crack, then standing in the light coming around the edges, illuminating all of the questions I can’t answer. And something else there, too, in the shadows, the ancient knowledge that I don’t want and didn’t ask for, something I only allow myself to think about in strange, tired hours: that one day, one of us will leave the other. That perhaps part of my work as her mother is to prepare her for the most likely of the two possibilities.

But that won’t happen, I tell myself each time that shadow bleeds in, either one of my secrets or one of my lies. What is the difference? Each is meted out in small doses, arranged carefully across the surface so as not to disturb the stillness of getting through the day.

*

Use simple words, the guides say, to talk about death. Stay calm, and be clear. Say, I have something sad to tell you. Say, The dog was sick and the doctors couldn’t help him. Be concrete, do not allude to stories of angels, of afterlives, of long journeys. Children struggle, they say, to understand the permanence of death, so be clear. He is never coming back to be with us, and I am sorry.

“Are you going to die, too?” she squeaks, snuggling into my chest. The last of the heavy waves of sobs for the dog have only just subsided, leaving behind little pieces of things she has yet to explore. Her little fingers grasp the fabric of my shirt, my neck and shoulders were soaked with her tears.

“No,” I lie. Then, “Not for a long, long time,” I guess. Finally, I say “And when I do, I’ll never leave you. I’ll always be with you.”

I say that because it’s what my mother said, because it’s what I think a mother should say. I say it because it’s as honest as I can be right now, in these very seconds, this mother to this child. I said it because that was what we both needed in that moment, at the vestibule of that heavy door and the eternal question that lay beyond it.

Children struggle to understand the permanence of death, the guides say. The guides say nothing about the permanence of motherhood, how it reaches through time, how the word itself conjures protection.

*

In the fall, we arrange eight eggs in an incubator that looks like a pink submarine, as if our chicks will hatch and take to sea. We count the days on a calendar and mark the time with stickers, she tells me all of her ideas for names. While the incubator hums, we talk about the endless possibilities: that we could end up with eight chickens, that we could end up with none, and how much our sweet, silly dog would have loved to be friends with a chicken. In the darkness, we shine the beam of a flashlight against the egg shells and she stares, her tiny mouth twisting in scientific concentration, forehead lined with the pursuit of proof. Success, she says, looks like the black dot of an embryo, the red threads of veins. Satisfied, she places each egg back into the incubator, all signs of life witnessed.

On the twenty-second day, I hold an egg to her ear and she waits, listens until she hears the peeping. They do it before they hatch. With the first swallows of air stored inside the shell, they call for mother.

-Jona Whipple

Jona Whipple is a writer, librarian, and archivist, in that order. She is currently pursuing her MFA in Fiction Writing at the University of Missouri-Saint Louis. Her stories and essays have appeared in Heavy Feather, Catapult, Bluestem, and others. She lives in Missouri with her husband and daughter.