Trying

I thought I’d finished coming out. I will be forty this year, and I spent my young adulthood struggling with my queer sexuality. There were the days of hiding and hoping no one would notice the desires that sometimes felt unnatural and unwanted, and the days of reveling in queer culture. There was the era in which I identified as bisexual, then lesbian, then bisexual again, until I eventually adopted “queer” a broad, fluid term applicable to anyone who isn’t straight. Coming out is a continuous process, but for the most part I felt like I was finished with slapping a label on my identity and presenting it to the world. I’d done what often felt like risky work of disclosing my sexuality to friends, family, my coworkers, and even occasionally my students, in the hopes that their awareness that their professor was queer would normalize it for them. I felt in some ways beyond the young, soul-searching, emotional distraught of my period of discovering my sexuality. I’m becoming a middle aged woman; I have grey hair, and I’m losing connection with any cultural references that my students would still understand. Surely I’m done with the identity crises.

And yet, there was this recurring, persistent part of myself that whispered I might not be. That my gender identity might need to be explored, and that I might finally have the language, space, and support to do so.

*

In many ways, my exploration of queer culture and my own sexuality informed my gender identity and the shape it could and could not take. As a teenager, when I began to understand myself as queer, I delved deeply into literature, pop culture, and music about and by queer women to try to understand the community I felt a part of. Of course, having little access to actual queer women in my small town meant my understandings were limited and overly reliant on specific tropes and patterns in media.

“Butch” and “femme” were terms that repeatedly appeared in narratives about queer women I consumed, but I struggled to fully understand their meaning. I learned that butch and femme were both queer women, but their gender identities—things like haircuts, clothing, and body language—were meant to be very different, and pop culture often suggested that butches were only attracted to femmes and vice versa.

As I learned more about these understandings of queer womanhood, I worried increasingly about where I fit into all of this. In my young adulthood, I wasn’t hugely girly, but I presented generally as feminine. I wore dresses and makeup for special occasions. I liked my body and the ways that it’d developed; after years of feeling like a string pole, I’d developed breasts and hips that I often enjoyed highlighting through clothes.

Because of this, I guessed, then, that I was femme. I stumbled forward with that as a tentative queer identity. I dated a butch woman, and one weekend we traveled to the big city to attend a drag ball, putting on our own formal wear. We wandered through the dim lights of the hotel room where the drag ball was located, and I took her arm even though she was much shorter than me, because it felt like the femme thing to do. I didn’t realize that my girlfriend would dump me later that night and hook up with a mutual friend in the same hostel room I was staying in, an incestuous dynamic that in retrospect is pretty gay—I guess I was a real queer after all!

Occasionally, my desires to act and appear masculine—“butch” being the only term I had for this gender identity at the time—came to the forefront. As a celebration of coming out as queer, I cut all of my long hair off. I loved the feel of the prickly, fuzzy softness of my buzzed head against the palm of my hand. During this period, my sister would occasionally refer to me as “Clark” when we were out at a bar, which we’d decided would be my drag name if I ever wanted to experiment with being a drag king. I yearned to be able to make women swoon the way butch icons like the Canadian singer k.d. lang did, and aspired to match her swagger and confidence, when in reality I could barely find queer women to kiss in my small town.

As I grew older, and solidified my sexuality as bisexual, and then queer, I let my butch aspirations fall to the background. I began dating men again, and wound up in a committed, long-term, loving relationship with a straight man. I never stopped being or feeling queer—and was quick to remind my partner Todd that I was not straight, lest he forget—but being feminine just felt easier in so many ways. It was a way to feel certain that I was attractive to my partner, and seen as appealing, respectable, or even just “normal” in public spaces.

There was an ease in bonding with women through the trappings of femininity. My female coworker would compliment my earrings and I would say, “Thanks! And you look great. I love this new haircut.” Or a group of female friends would vent about the sexism we faced in our daily lives. Even though I didn’t always feel totally aligned with femininity or fully represented by womanhood, there was still solidarity to be found in sharing experiences of living in a patriarchal society.

Femininity in adulthood was both a comfort, a form of social clout, and, in specific ways I couldn’t always articulate, not enough and too much. My pull toward masculinity continued in my adulthood; I was just simply at a point in my life—and within a social circle—in which I no longer understood that pull within the framework of butchness. That had occurred partly because it felt like I had outgrown some of my obsession with nailing down my queer identity and because my desire often existed outside of any sexual context.

In my young adulthood, my brother Brendan could occasionally talk me into helping him lift heavy things by complimenting my strength, which felt especially gratifying given that he was the athletic and muscular sibling; if he considered me strong, then it must be true. Once, at his request, I walked out of our parents’ house out to his parked red SUV, a bit dinged up but still in good shape, which had his kayak strapped onto the roof rack. I positioned myself at the back of the kayak, fitting my hands underneath one corner of it, and waited for Brendan to instruct me. “Okay, lift!” he exclaimed, and the two of us carried the kayak off the car and onto the green grass beside us. Brendan smiled back at me, his dark blond hair made golden in the sunlight, and announced, “Okay, that’s it. Thanks, Muscles!” I hoped against hope that the nickname would stick and that he would always see me as like him, a bro who he could depend on for physical strength.

The desire to be seen as strong and capable remained a recurring theme in my adulthood. The two years in which I did Brazilian jiu jitsu (or BJJ for those in the know) made me feel both more masculine and more feminine. I was newly inspired into doing push-ups, which I’d always found boring, because they made me better at grappling and I felt a thrill at developing the visible arm muscles I’d yearned for for years. I had a probably outsized confidence in my new skills, like the night when I went to a concert and a loud, big, drunk man was yelling and causing chaos, and I briefly thought, “I could probably take him, right?”

Yet I was also taking classes aimed specifically at women and being told I would need to strategize for how to fight against the men who were, the instructors suggested, likely always going to be stronger than me. I felt in many ways safer taking classes with women, especially when I overheard some of the male students making sexist jokes, but they often got distracted talking about raising kids or their relationships with their husbands. I sometimes felt like an outsider. Didn’t anyone want to get swole? Didn’t anyone want to explore their relationship to masculinity through BJJ?

And yet, despite the struggle to find spaces to explore my identity, gender euphoria snuck up on me with unexpected strength. There was the birthday when a friend gave me a joke gift of a set of fake moustaches. We all took turns wearing them, but I really wore them, well beyond using them as a silly prop. The hard black plastic was clipped under my nose uncomfortably, but I kept them on regardless, preening as people told me how good I looked. In moments like these, I wished to just have facial hair. Not the stray chin hairs that the frigging patriarchy had trained me into plucking, but a full, lustrous mustache or a beard. Not all the time, but as a gender accessory for the days that that felt right.

I knew how good I felt in these moments, and I couldn’t ignore the gendered fantasies that played in my head: the ones in which I was able to pop off my breasts and put on a man’s chest at will; in which I had a flatter body that could pull off more androgynous clothing; in which I was a gay man who could seduce other gay men. But I didn’t have the language for what I was feeling.

So many of the dominant narratives about transgender and nonbinary people I’d consumed felt like they didn’t fit me. Much of media represented transgender people as feeling that they’d been born into the wrong body and AFAB (assigned female at birth) nonbinary people as feeling a deep discomfort, even hatred, for femininity. I worried that I didn’t have the right story. I was fairly certain I didn’t want surgery or to take hormones and I didn’t hate my body or femininity. I just wanted options. I wanted a range of gender identities. I wanted to one day look like James Dean and make queer women blush as I walked by, and the next be an attractive, feminine woman to my mostly heterosexual male partner.

Eventually, these thoughts and feelings became too overwhelming to deny, and the idea of being genderqueer seemed increasingly possible. I had more friends who were recognizing that they fit somewhere outside the gender binary, I had media to help guide me, and I had a partner who I trusted would love me no matter what shape I took. Thrumming with both fear and hope, I began to stumble my way into a more explicitly genderqueer presentation and identity.

I began leaning into masculinity and androgyny, trying to match what I felt on the inside with the outside. I got a new, short haircut, from a trans hairdresser who understood how affirming the right hair could be. I worried I might regret cutting off so much hair, but instead I found myself grinning wildly into the mirror as my hair got shorter. The reveal of my newly androgynous self, within this stereotypically feminine place, was equally delightful as any makeover montage in a nineties movie, where the “ugly” woman is turned beautiful through makeup and a new hairdo. The strong smell of hair spray surrounded me, and I felt like I was seeing myself in the mirror for the first time in a long time. My hairdresser smiled smugly at me in the mirror, proud of her work, and told me, “You look like a sexy gay businessman!”

Experimenting with my gender presentation could be sometime be challenging, even on a practical level (should I invest in wigs??), but it also felt incredibly liberating. To have a friend playfully refer to me as “daddy” or call me handsome, to have a partner who asked what language I wanted him to use when talking about how attractive he found me—it felt like more than I could have hoped for.

As exciting as it was to be seen increasingly as I wanted to be seen—as more than a woman, as a fluid creature who occupied many different kinds of gender identity—this sense of freedom made the restricting moments all the more apparent. Coming out as gender queer , if only in my head initially, also made me realize how much people defined their understanding of me through femininity and womanhood.

Even with people with whom I felt a genuine bond, their gendered understandings of me felt more and more inaccurate. I worked as a professor in a post-secondary institute and genuinely loved many of my fellow instructors. But gender had always played a role in these dynamics. Most of my coworkers were in straight relationships, had children, and often used heteronormative humor to bond. My male colleagues would joke about “the wife” always being the boss, or my female coworker would half-jokingly complain about her husband never cooking any meals, despite her working a more than full time job.

I’d never related to their assumptions about my role as a wife. I once responded to one of these jokes by staring down my coworker and saying in a deadpan tone, “My partner and I really like each other, actually.” As I grew into a more fluid understanding of my own gender identity, it became almost painfully obvious how wrong they were. The idea that I was defined by my ‘wifeness’ was increasingly ridiculous when compared to the way that I thought about myself in my head. Random coworker, does your wife also spend work meetings daydreaming about buying a binder and a strap-on?

Even the kindnesses that are enacted on people assumed to be feminine began to feel unkind. In one course I taught, students had to complete activities in journals, which I would collect at the end of class. I piled the journals, with their shiny metallic coils or soft, floral covers, into my burlap tote bag. I picked up the tote and slung my second bag, holding my laptop and water bottle, over my shoulder. One of my male students said, “Dr. Clare, are you going back to your office? I can carry the journals for you.” Automatically, I resisted, “Oh, no, it’s fine! I can handle it.” Still he lingered, saying, “Are you sure? I don’t mind!” I finally managed to send him on his way, knowing he couldn’t understand that his thoughtful gesture had sent my thoughts swirling. Would the student have made that same offer to a male professor? I was taller than him and had arm muscles that were visible if I flexed them, an act I sometimes performed in the mirror at home— should I show him my muscles?

I stubbornly dragged both bags back to my office, but quickly it became apparent that the bags were indeed heavy and awkward to carry. Taking a break in the pedway between the buildings, rubbing at the red marks left in the soft skin of my hands, I felt my belief in myself as strong and capable wavering. I wished for the kind of muscular ease of my male partner, Todd, who hauled jugs of water or heavy bags of kitty litter seemingly without thinking twice about it.

Acting on the nonbinary fantasies I’ve had in my head for years or longer has been both liberating and terrifying. Keeping my genderqueer thoughts in my head was isolating, but it also meant that they were safe and hidden. Changing my pronouns to she/they, getting my short androgynous haircut, and talking to my community about being nonbinary like feels my brain and heart have been cracked open for anyone to see, in the best and worst ways. What if my sister feels differently about me now that she knows that I don’t only identity as a woman? What if I can never get my colleagues to see me as anything other than cisgender? What if the LGTBQ people in my life see me as an imposter?

There’s the part of me that’s playing catch up for all the time I couldn’t present as anything than cisgender; I have the urgent sense that I must unravel every part of my gender identity now. When I give each genderqueer action the weight of forever it becomes too heavy to carry.

But playing with my gender identity and presentation feels lighter, more exciting, and more open to change and exploration. I am trying to try, a scary thing for a person who has been generally happy in a well-established community, job, and relationship.

But oh, the things that can come from trying.

My partner Todd and I are getting ready to go out to a movie. I can feel that the warmth of the day has cooled, so I put on my faux leather coat that I bought at a Bootleggers going out of business sale (it was half off! A steal!). With its gold zipper and cheap black plastic material, the coat is not signalling high fashion, but it’s doing its job of giving me a more masculine silhouette.

Todd turns and grins at me, exclaiming, “You look like a real bad boy!” I warm at the riff on a recurring joke between us (neither of us are particularly bad) and the gender affirming compliment. I feel seen right down to the deepest bits of me. I feel loved for all of me, not just for the feminine bits that I sometimes worried he liked the most, but for every grey, in between, genderqueer thing in me too.

I open our white front door, nod in a way I hope seems manly for Todd to exit the house ahead of me, and go out into the world, eager to see what it has in store for me.

-Clare Mulcahy

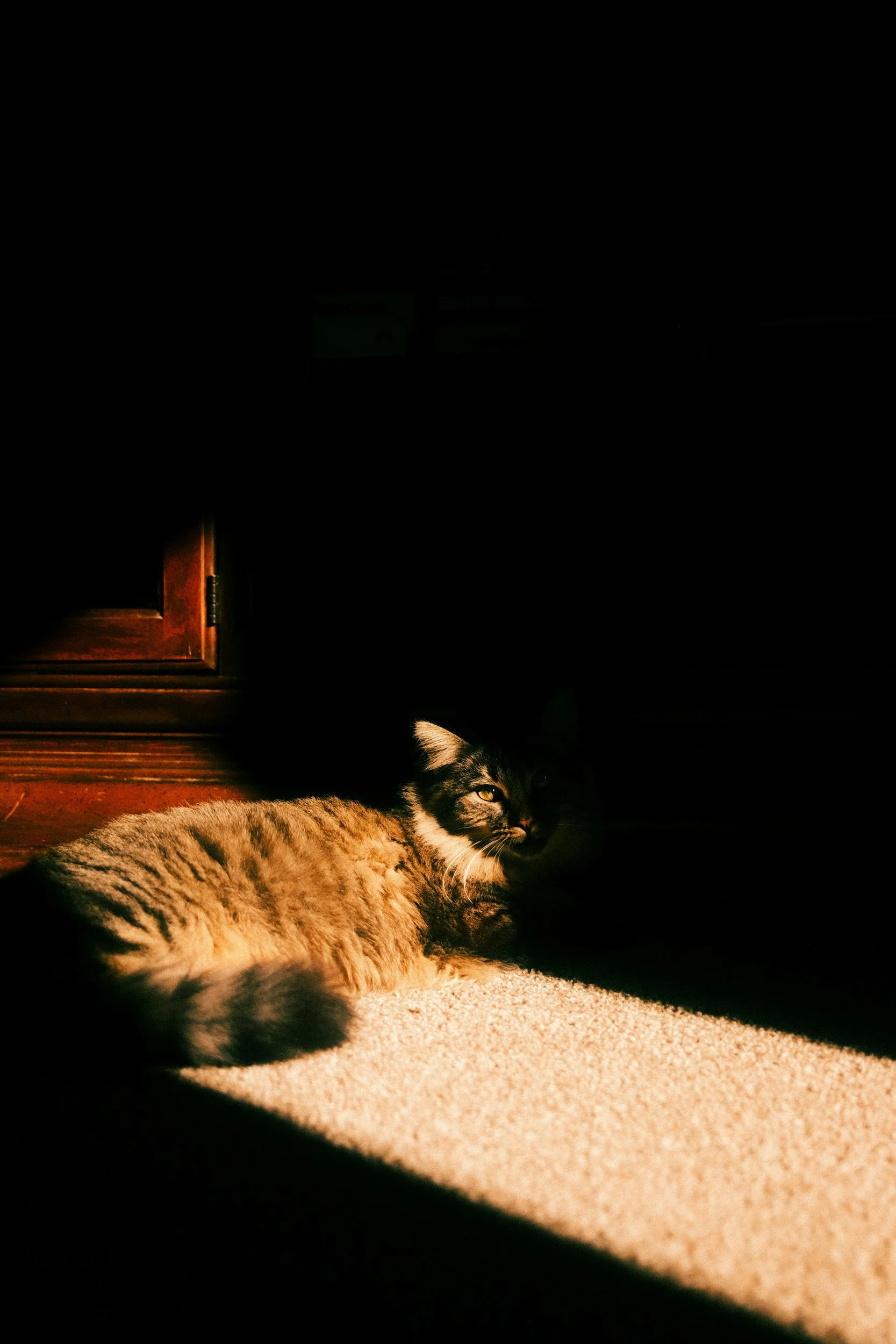

Clare Mulcahy is a professor of English literature, with a particular interest in representations of race, gender, and sexuality in pop culture. They live in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, with their beloved partner, Todd Merkley, and two cats. Special thanks to their writing partner, Leigh Dyrda, for her humour, enthusiasm, and sharp eye.