Proof of Life

“The great difficulty is to say Yes to life.”

-James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

It took seven years of therapy for me to recognize that the gaping wound in my heart is not the child of grief or exhaustion, but of a life un-lived. I have made no great mistakes or spoken the silent, shamed words of “I should not have done that.” I have not done anything. My emotional destruction has been predicated on loss, trauma, and frustration. I wish it was the result of having my heart broken by someone I was in love with, or being stuck in a cycle of taking drugs that will damage my brain by thirty, or spending money under the false notion that I have a six-figure salary. At least I would have proof I could endure risk and confront it with confident uncertainty.

Part of me fears that I am no longer human. That the mess, wreckage, and rue intrinsic to this force called life are lost within the compounds of my psyche. I am the only daughter in an immigrant family, which is another way of saying that I have spent the twenty-four years of my life playing it safe. My “great life,” the one I wish was my real life, rests in the four pounds of my brain. There are two credos which wove the fabric of my childhood: “speak only when you are spoken to” and “there is a time and place for certain behavior.” Both were intended to instill discipline at a young age, and my brother and I were often marveled at by invasive strangers for never crying in public. What kind of child does not cry in public? A fearful one? A diminished one? I am afraid that, instead of respect, my brother and I were raised under the impression that regret, punishment, and consequence were the real Boogeyman, the thing that lurked and loomed.

I am months away from my impending midlife crisis and while I am not meek, I am hesitant and non-confrontational and contained within my flesh. I once smoked a cigarette and the smell that lingered between my pointer and middle finger had me weeping on the ground days later, begging for absolution from a sin that was not even close to damning. I once had grand aspirations about a life full of devious affairs, spontaneity, and a satiatingly successful writing career. By the time I was thirteen, these idealizations were beaten out of me. I replaced the devious affairs with an aversion to teenage pregnancy and generational familial shame. I was not allowed to date until I was eighteen. The spontaneity was slaughtered by diatribes about “building a life of stability” and creating a strong foundation at a young age. I pray every night that the writing career is the pillar that survives.

Today, I sustain myself on fantastical imaginings of a life I could have. Imaginings that have been replayed so often that they are losing their saturation. The problem is that they require a type of risk that demands sacrifice, humiliation, and surrender. The type of risk that brings me to my knees in prayer, begging God for one more chance to prove I can make good decisions, too.

There is one version of life where I live in New Mexico and I own a red 1990 Chevrolet 1500 and live alone, isolated from friends and family. I am forty miles away from the nearest grocery store and am deeply familiar with the grooves of my saddle blanket seat covers. I drive down an open dirt road, going forty-five mph, while the sunset burns strong in my periphery. Wisps of hair breed in my mouth and I do nothing to remove them. I am at the whim of nature and gravity and I am barefoot and strong.

There is another version where I publish a few books and settle down in an open apartment—one with a balcony that accommodates a morning sun-soak—somewhere in Spain. I sleep on laughably expensive sheets, but I worked hard for them. In the summer, I escape to a small, seaside bed and breakfast. I made a life for myself where I am confident, adored, and comfortable. My friends visit me frequently and I beg them to move across oceans and sleep in my bed.

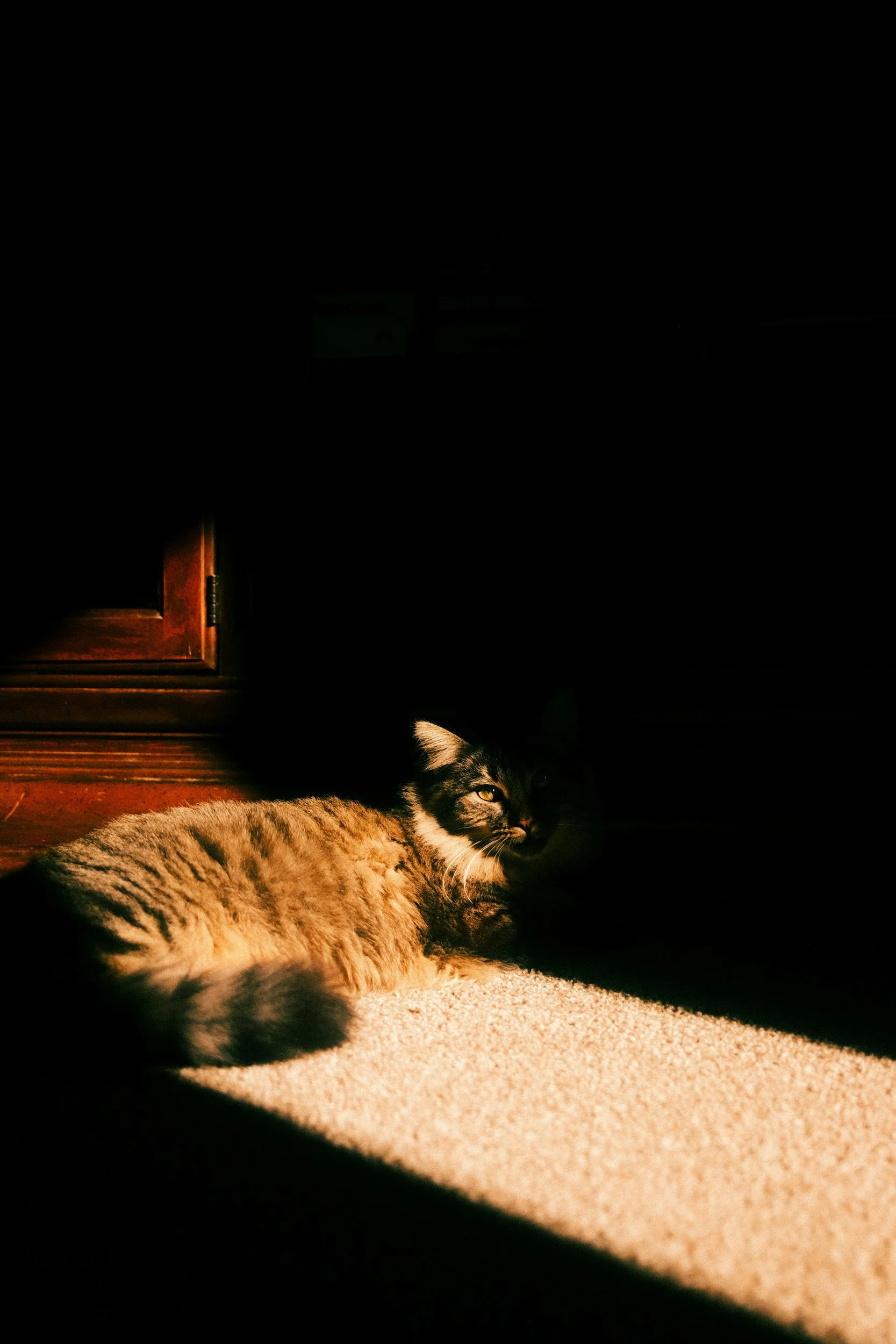

My personal favorite, however, is the one where I live in Santa Cruz, in a small house with a worn-in living room and rarely used kitchen. I have two daughters and I teach them how to feel trees breathe. The dirt is rich and pillowy under our fingers and we make silly faces at one another. I used to think I would not have children because I could not bear the thought of loving someone that much. But, we worship the altar of douglas firs and laugh at the dizzying vertigo their height incites.

In these un-lived worlds, I am someone sensual. Someone who is soft. Someone who is open. In these visions I have been devastatingly in love and devastatingly out of love. In these make-believe landscapes, my mother does not ask me to forge into frosty eastern nights to take out the recycling, even though my brother is sitting idly beside me. In these reveries, I am no longer the “emotionally intelligent one of the family.” There are no demands for my competence or my capability.

I have been blessed with access to psychiatric help and a $70,000 per semester education at an “elite university,” and all it taught me is that I think too much. I spent thousands of dollars just to be told that I do not exist in my body. My mom taught me from a young age that one of the most valuable things one can do is live in integrity with themselves. But when your entire life has been constructed on the principles of an elder, someone belonging to a generation without dating apps or ApplePay or social media, what does that leave you with when the time comes to abandon the cautious version of yourself?

The riskiest act I pursued in 2025 was losing my virginity to a stranger I met online and who was much older than me. I doubt whether this was a real risk as, in the buildup, climax, and denouement of our “relationship,” I wrote lists about where we could be in one month, three months, and six months. I tested dialogue in the shower, snipping and tightening justifications for my behavior. I wanted to mitigate stress, guilt, and embarrassment. I jumped at this opportunity to have sex because I thought it would enrich my writing. Everything that came from my hands had previously been scripted by insecurity and anecdotes that had more to do with friends or family than myself. I wanted to make a decision that proved I could be like other twenty-something year olds, ones who stockpile stories about disgustingly ravenous encounters that forced them to reconstruct what they thought to be true of themselves. I do not think about risk in the language of weight or consequence, but in the language of cost. What bartering system did I subconsciously enter in succumbing to human impulse? Did I exchange my integrity? My purpose? My self-esteem and belief that I “have a good head on my shoulders” and a strict moral code? I likened the act of sex to undergoing an ego death. The night I crossed over into the murky confusion of “real adulthood” my soul split into two, birthing a quivering and hungry infant. Her nascent cries were for all-nighters and hangovers and decisions that would leave my parents disappointed. I still do not know how to nurse this newborn iteration of myself without questioning the foundation of my integrity.

In eight months, I will move to Paris. This was another risky decision, one that waited in limbo while I asked myself whether I could handle exchanging personal comfort for life experience. For so long, risk has functioned as the antagonist in my life. It was a weapon and reminder that I could easily destroy my life. Introspection has led me to wonder if the real risk, the one that threatens my “great life,” is living a disingenuous life, simply because I am used to it. As this new year unfolds into spring, summer, and fall, I hope that every risk I take knocks me onto my ass and weighs heavily on my heart.

-Jasmine Cheek

Jasmine Cheek is a Brooklyn-based writer, soon pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing. She uses Substack as her main writing platform, under the pseudonym Girl Genius. Her portfolio consists of short fictional stories, personal essays, and longer form creative nonfiction. She is always looking for book recommendations, preferably non-fiction.